At the outset of the now two-year pandemic, communities around the globe struggled to adapt to and comprehend a world more unsafe and on edge. Fear and chaos furiously erupted, infiltrating and altering all elements of our lives. But as case counts soared, fueling crucial data about the virus’ severity and effects, a curious consensus arose about the consequence of a Covid infection: you could either develop severe symptoms and be hospitalized or experience a surprisingly mild infection, exhibiting only familiar cold-like symptoms, or even none at all.

Despite how much we’ve learned about the coronavirus, how strikingly the pandemic has evolved, and how dramatically the public’s view of the virus has shifted, the belief that Covid will either force you into an ICU or simply into your bed for a few days hasn’t faltered. This narrative, echoed consistently by experts and laypersons alike, has persisted, continuing to inform how we perceive the virus and its risks.

Unfortunately, our understanding of Covid-19 as either a deadly disease or moderate infection hyper-emphasizes what we currently know about the virus’ most immediate impacts. What it fails to do is acknowledge the often overshadowed though perilous long-term toll of the virus, a concerning phenomenon garnering growing awareness as the long-term ramifications of the pandemic begin to crystallize.

Consider for a moment that days after your family’s long-anticipated holiday party, you get unlucky and test positive for Covid. For five days, you’re trapped at home, battling a sore throat, a nagging cough, and an incessant runny nose. Luckily though, your symptoms don’t worsen, and before you know it, your health returns. But soon after, you observe that something’s off. A quarter of the way into your daily one mile run, you fail to push on as your heart pounds and exhaustion peaks. While resting at home, you helplessly worry as your heart rate suddenly soars. And upon returning to school, you struggle to reconnect with a friend as you fail to think up any words at all.

This is long Covid, a complex sickness defined as a “wide range of new, returning, or ongoing health problems” that may follow an initial infection. Thought to affect approximately ten to thirty percent of those who develop a Covid infection, long Covid may even develop in patients who experience mild or asymptomatic infections. The symptoms, spanning a broad spectrum of afflictions, include fatigue, diarrhea, headaches, problems thinking and concentrating (brain fog), heart palpitations, shortness of breath, and more. Patients suffering from long Covid often deal with a complicated mixture of these symptoms.

The quest to better understand what causes long Covid and what can be done to treat it is paramount. Once blessed with good health and well-being, patients with long Covid now face some of the toughest physical, mental, and emotional challenges they’ve ever endured. Their tenacity, resilience, and strength should not go unnoticed. Still, fighting this illness will require more than just willpower. We need science to illuminate an effective path forward, one that clarifies the causes of long Covid and the mechanisms to combat it.

Luckily, research about long Covid is mounting, shedding light on some much-needed answers. Here’s what the current science has to say about long Covid.

In a large study recently published by the Cell, a prominent research and biology journal, researchers revealed four risk-factors that seem to elevate one’s likelihood of developing long Covid, regardless of how severe or mild their initial infection was. The first factor is the amount of coronavirus in the body early in the course of infection. If initially infected with very large amounts of the virus, a patient may be at higher risk for developing long Covid. A second factor is the circulation of a class of harmful proteins–autoantibodies–that antagonize important materials and structures in our body. For example, autoantibodies can attack crucial proteins and carbohydrates in our cells and organs. Furthermore, the study found that long Covid is more likely to occur in patients whose initial infection reactivates a virus known as Esptein-Barr virus (EBV), the most common cause of infectious mononucleosis, or mono. A common suspect in many childhood viral infections, EBV eventually surrenders its infectious weapons, later becoming inactive in the body. Still, EBV may not permanently remain inactive; certain influences, such as the coronavirus, may enable its reactivation. Lastly, patients with Type II diabetes were discovered to be at greater risk for developing long Covid, though experts, including those involved with the study, believe that further research will likely point to a number of other conditions that also increase one’s chances of developing the illness.

The study casts a light on those most vulnerable to long Covid development, granting doctors and scientists the ability to brainstorm effective prevention and treatment measures against the illness. Should further research certify the study’s findings, Dr. Steven Deeks, an esteemed HIV expert and physician, believes that that would represent a huge breakthrough, arming clinicians with the tools necessary to “actually design interventions to make people better.” Still, more research is key, and until further studies confirm the veracity of the study’s findings, experts encourage tempered optimism.

But the factors that increase one’s risk of developing long Covid represent just one side of the biological equation. How does long Covid give rise to such a broad and puzzling array of symptoms? Why does long Covid even occur in the first place? The answers, though nascent and speculative, are steadily accumulating.

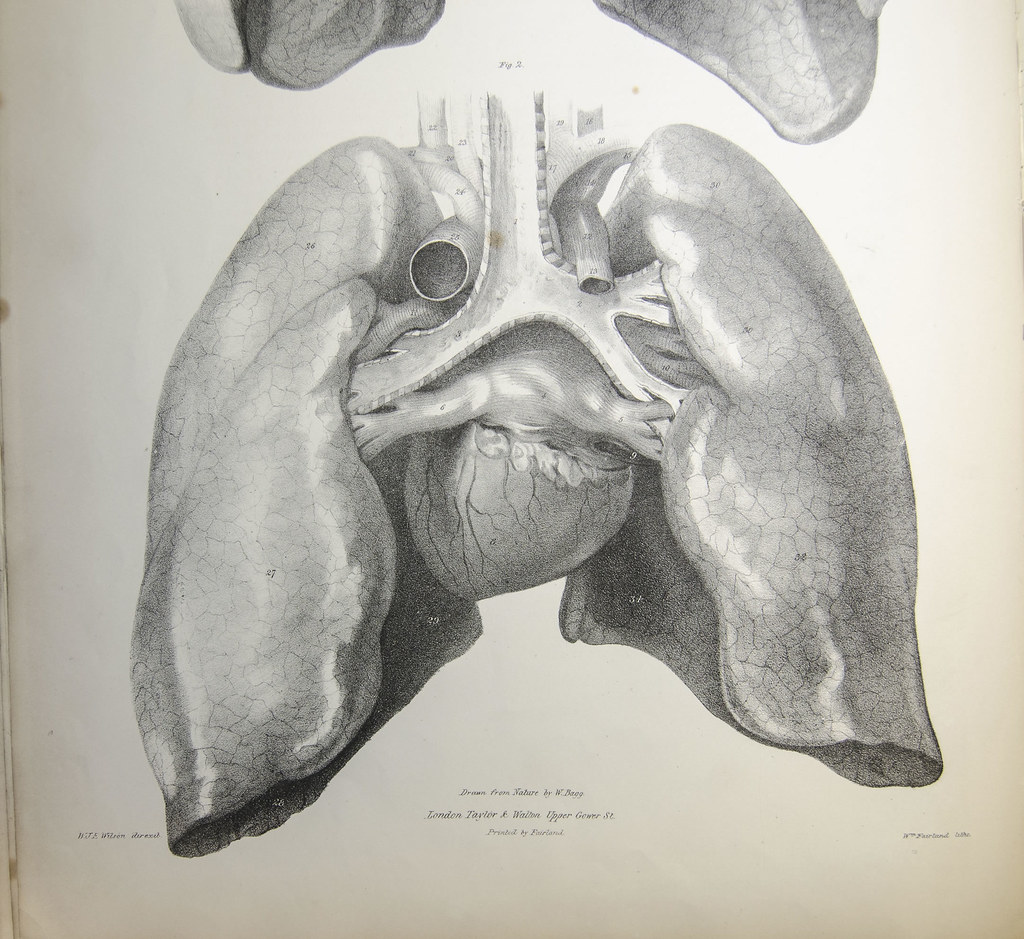

Long Covid appears to take aim at four of the body’s most foundational systems: the immune system, the circulatory system, the brain, and the lungs. Let’s first explore long Covid’s effect on the immune system.

Patients with long Covid exhibit altered immune activity, according to one study. Participants with long Covid displayed overactive immune function, described by the authors as a “sustained inflammatory response.” A large batch of symptoms is thought to follow, giving rise to a broad set of issues affecting various regions of the body.

But what kicks the immune system into high gear, and why does its hyperactivity produce long Covid symptoms?

Current research points to three possibilities. The first has to do with the virus itself. During infection, coronavirus particles reach many areas of the body and appear to adamantly stick around wherever they land (like clingy guests at a dinner party). Because of this, pieces of the virus can be found within tissue throughout the body for weeks or even months after infection. Researchers are now trying to determine if the viral particles that remain fuel inflammatory events in the body as the immune system struggles to get rid of the virus and whether such events can trigger common long Covid symptoms, like brain fog. Another possibility involves recent findings that expose “high levels of autoantibodies” in the body long after infection. As earlier mentioned, autoantibodies are proteins of the immune system that can harm our own tissues. Therefore, the presence of autoantibodies in long Covid patients could boost immune activity and also foster persistent symptoms as a result of tissue damage. Finally, it’s thought that the coronavirus can reactivate a number of inactive viruses, forcing the immune system into overdrive as it tries to fight off multiple enemies.

Long Covid’s impact on the circulatory system is complex. A number of studies are just beginning to reveal why some long Covid patients struggle to move oxygen throughout the body. Here’s what we know so far.

In a recent study, long Covid patients failed to sufficiently oxygenate their muscles whilst pedaling a stationary bike despite exhibiting no “abnormal chest CT scans, anemia, or problems with lung or heart function.” How come? One answer may involve damaged nerves and something called dysautonomia, a class of conditions that involve some sort of dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system, the branch of the nervous system that controls the functions we don’t consciously direct, like “heart rate, breathing, and digestion.” In another study, researchers uncovered that long Covid patients contain very small blood clots that normally “break down” once a Covid infection subsides. Tiny as they are, “these clots could block the tiny capillaries that carry oxygen to tissues throughout the body,” substantially decreasing oxygen uptake. What’s more, increased levels of cytokines–chemicals released during inflammation–in patients with long Covid could harm our cells’ mitochondria, the well-known powerhouse of the cell. Mitochondrial damage may inhibit the ability of cells to consume oxygen given the organelle’s central role in cellular function.

Furthermore, long Covid has been shown to disturb normal brain function. The root of a perilous array of symptoms like dizziness and short-term memory loss, long Covid’s disruption of crucial neural processes is especially cruel and debilitating.

However, we currently don’t have a great sense of how long Covid endangers the nervous system. Recent research has raised only two possibilities thus far. The first involves a hyperactive immune response, characterized by the “over-activation of immune cells called microglia,” which engulf harmful pathogens in the brain. This response is reportedly akin to the overactivity which fuels age-related cognitive decline and certain neurodegenerative diseases. The second possibility has to do with how much blood the brain receives. In a recent study, long Covid patients were found to supply inadequate levels of blood to the brain, a startling finding given the blood’s crucial role in delivering oxygen to the body’s cells.

Unfortunately, our knowledge of long Covid’s impacts on the lungs is quite limited. Current knowledge about this topic is based upon very new research that has yet to offer any certain explanations. Nevertheless, research on the subject is being done, piecing together the elusive pieces of this intricate puzzle.

In a recent small study of long Covid patients, researchers discovered that many subjects “took up oxygen less efficiently than healthy people did,” offering a plausible explanation for the shortness of breath that many with long Covid frequently experience. Very tiny blockages, or microclots, in the patients’ lungs are thought to cause this problem, impairing normal oxygen uptake. Still, substantially more research is required to assess the veracity of these findings.

I admit it: the pandemic has felt painfully long. The last two years have been filled with incredible uncertainty, pain, and frustration. However, contrary to growing images of packed sports arenas, lively concerts, and unmasked gatherings, the pandemic is by no means over. While certain phases of the pandemic have admittedly reflected some measure of calm and normalcy, these moments do not change the reality that Covid-19 is still with us. We are in a public health crisis. So even as we embrace the increasingly endemic nature of the virus, the long term toll of the pandemic will continue to unfold, impacting the lives of countless individuals all over the world. I do not express this gloomy sentiment with the goal of stoking fear; panic never constitutes an effective response or mentality. My intention is rather to emphasize the immense complexity of this virus, to shed light on the daunting though realistic aftermath of this brutal pandemic.

Sources:

- https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/02/19/science/long-covid-causes.html?searchResultPosition=7#circulatory

- https://www.runnersworld.com/runners-stories/a33984743/covid-19-diagnosis-natalie-hakala/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/12/well/move/long-covid-exercise.html

- https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/11/health/covid-survivors.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html

- https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/what-doctors-wish-patients-knew-about-long-covid#:~:text=Long%20COVID%E2%80%94or%20post%2DCOVID,with%20SARS%2DCoV%2D2.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/25/health/long-covid-risk-factors.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2703183/

- https://www.cdc.gov/epstein-barr/about-ebv.html

- https://infectiousdiseases.ucsf.edu/people/steven-deeks

- https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/02/19/science/long-covid-causes.html

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41590-021-01113-x

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0012369221036357?via%3Dihub

- https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/12/well/move/long-covid-exercise.html

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/6004-dysautonomia#:~:text=Dysautonomia%20refers%20to%20a%20group,your%20heartbeat%2C%20breathing%20and%20digestion.

- https://cardiab.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12933-021-01359-7

- https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/03/health/long-covid-treatment.html

- https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abm2052

- https://faculty.sites.uci.edu/kimgreen/bio/microglia-in-the-healthy-brain/