When most Americans think of professional tennis player Serena Williams, they associate her with strength, agility, and championship. This mental image is no surprise when considering her 23 Grand Slam championship records–a victory making her one of the greatest players of the Open Era. Despite her athletic success, as a black woman in America, Williams is one of millions predisposed to maternal health complications.

A day after delivery, Williams suffered from a pulmonary embolism, a condition in which arterial passage within the lungs is hindered by blood clotting. Soon after falling short of breath, the new mother warned her health team of an expected embolism and requested a CAT Scan (cross-sectional imaging) along with IV heparin (blood thinner). Williams’s personal history of blood clotting left her cautious and well aware of the symptoms preceding such a complication. Nonetheless, her staff nurse initially disregarded her concern, citing Williams’s assumed “confusion” as an adverse effect of her pain medication.

Despite complexities in her health background, Serena Williams is one of many African-American women subjected to disproportionate rates of birth-related complications. In fact, the maternal mortality rate (MMR) for black women in the United States is three to four times greater than the rate for non-Hispanic white women. While cardiomyopathy, pulmonary embolisms, and hemorrhages are the primary medical causes of mortality, the underlying sources of this racial disparity in MMR may not be as pathophysiological as we think. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, limited healthcare access, late diagnoses, and “failures by doctors or nurses” are primary sources of this drastic disproportion.

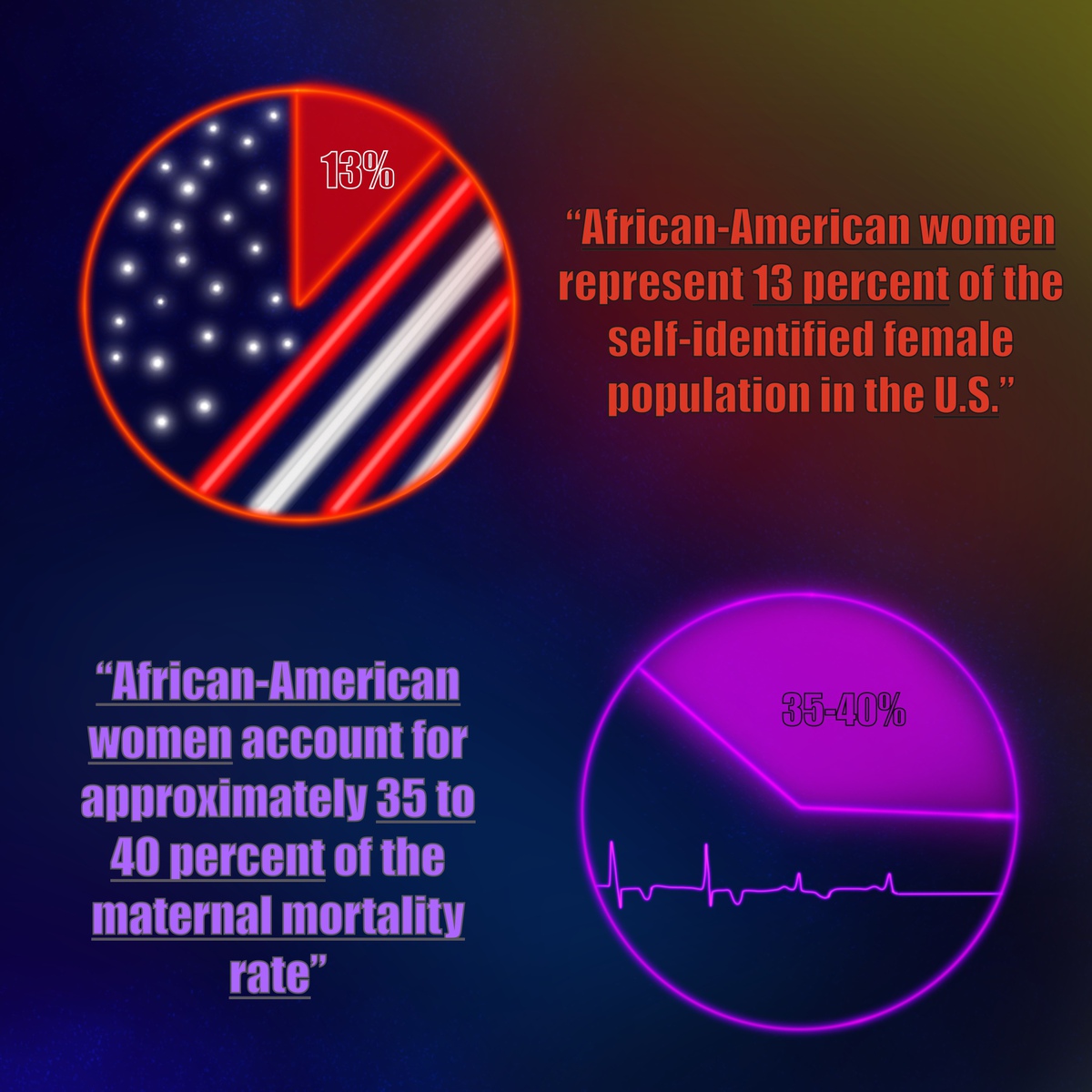

Maternal mortality is broadly defined as death due to the occurrence of “pregnancy complications, a chain of events initiated by pregnancy, or the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiologic effects of pregnancy within a one-year timespan post-partum.” Each year, nearly 700 women die before, during, or shortly after delivery. While African-American women represent 13 percent of the self-identified female population in the United States, they account for approximately 35 to 40 percent of the MMR.

Nonetheless, before dissecting the racialized implications of a multicultural healthcare system, it is important to address potential confounding variables. Studies found persistent negative outcomes in African-American maternal mortality even when participants were controlled for significant educational and socioeconomic differences. For example, a comparative analysis of African-American (n=60) and Caucasian (n=47) females presented a 3.07 to 1 ratio of pregnancy-related death between the two demographics, respectively. This threefold increase in MMR for African-American women is present despite the study’s control of “gestational age at delivery, maternal age, income, hypertension, and receipt of prenatal care.” The analysis therefore concluded a persisting association between maternal mortality and black racial identity.

Similarly, a New York-based examination of sociological associations with MMR found that African-American women who earned a college degree or higher still died at over twice the rate of non-Latina white women who did not complete a high school education.

This trend is maintained in comparisons of African-American and non-Latina white women below the Federal Poverty Level. Between 2008 and 2012, African-American women who were less than 10% below the poverty line presented an MMR four times greater than white women over 30% below that level. Such findings reiterate a consistent disproportion in maternal mortality despite accounting for rudimentary social confounders.

As social controls allude to other sources of racial disparity, it is critical to assess the genetic bases of labor complications. As aforementioned, the immediate medical causes of death before, during, or after labor include cardiac disease, hypertension, pulmonary embolisms, and excessive bleeding. However, it is relevant to address the underlying causes of such complications and to examine potential genetic predispositions to maternal death.

Hypertension affects the African-American community at a larger magnitude than any other racial group in the United States. Research indicates that nutritional and behavioral factors do not fully account for such differences. Similarly, genetic polymorphisms have not been studied extensively enough to explain the hypertensive prevalence within this particular demographic.

Many theorists propose that environmental stressors, including job-related stress and racial discrimination, are attributable factors. However, there is limited literature pinpointing the precise relationship between stress levels and measured blood pressure in this demographic. One assessment conducted by the Jackson Heart Community evaluated this relationship, finding statistically significant correlations between self-reported stress and developing hypertension. Altogether, the study validates the impacts of psychosocial stressors faced by the African-American community.

Though the social and health-related causes of maternal death are not mutually exclusive, it is evident that disproportionate health barriers exist for black women in the United States. While empirical data shows room for development, anecdotal reports depict a consistent central theme: African-American women’s health experiences are hindered by implicit bias. Implicit bias, or the “unconscious attribution of particular qualities to a member of a certain social group”, affects the relationship African-American women have with their healthcare providers.

One NPR survey examined this relationship through a series of questions relating to personal encounters with healthcare discrimination and patients’ resulting comfortability with hospital visitations. 33 percent of participants recounted instances of discrimination during hospital visits, and 21 percent reported avoiding health evaluations due to fear of such discrimination. Further, such experiences are racially incongruent with those of non-Latina white Americans and partially account for unequal health outcomes pertaining to maternal mortality.

A ProPublica article described the healthcare inequities that arise when social prejudices turn to discrimination:

“In the more than 200 stories of African-American mothers that ProPublica and NPR have collected over the past year, the feeling of being devalued and disrespected by medical providers was a constant theme. The young Florida mother-to-be whose breathing problems were blamed on obesity when in fact her lungs were filling with fluid and her heart was failing. The Arizona mother whose anesthesiologist assumed she smoked marijuana because of the way she did her hair. The Chicago-area businesswoman with a high-risk pregnancy who was so upset at her doctor’s attitude that she changed OB-GYNs in her seventh month, only to suffer a fatal postpartum stroke.”

Several studies further investigate the medical downplay of pain experienced by African-Americans. A meta-data analysis of analgesic (pain-reducing) treatments found that, on average and across various settings, black patients were 22 percent less likely to be prescribed pain medication relative to their white counterparts. This discrepancy is largely rooted in misconstrued implicit biases surrounding the pain durability of black patients. According to one 2016 study sourced in Proceedings of the National Academies of Science and cited by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), “40% of first and second-year medical students endorsed beliefs that ‘black people’s skin is thicker than white people’s.’” Such alarming claims are partially rooted in 19th-century fallacies that individuals of black descent have less sensitive nerve endings. The prevalence of this misinformation undoubtedly yields diminished quality of care received by African-American patients.

The racialized health disparity model in the United States is further supported by statistical comparisons of infant birth weight in African-Americans mothers to the birth weights of Caribbean- and African-originating mothers. Abnormally low birth weights are a significant indicator of poor infantile health or limited gestational maturation and often allude to the quality of maternal health. Racial variance in birth weight may therefore explain disproportionate MMRs in the United States.

However, one study found that the average birth weight of children born to African or Caribbean mothers was significantly (> 100 grams) higher than that of children born to African-American mothers raised in established households. Contrastingly, the birth weight in black immigrant mothers, who did not spend the majority of their lives in the U.S., was approximately equivalent to that of white mothers. This finding supports the hypothesis that black women in America face social inequities and chronic stressors unparalleled in other geographical societies, as racial genetic predispositions do not explain variances in maternal and infantile health.

As the national MMR gradually declines, the statistic remains unimproved, if not worsened, for the African-American demographic. This public health discrepancy is attributable to more than financial, educational, or underlying health conditions–it is indicative of a systematically flawed institution.

While genetic predispositions and social barriers do affect the likelihood of maternal mortality, they are not the sole determinants for drastically disproportionate MMRs. Inadequacies in healthcare, including Medicaid coverage and access to prenatal care, impede health equity across the United States. Medical treatment consisting of unintentional implicit biases likewise obstructs opportunity for progress in maternal mortality. To address this public health issue, medical institutions must increase social training for healthcare workers. Similarly, they must emphasize the utilization of a patient-centered approach, which includes actively validating and responding to the self-reported symptoms of all patients. Finally, studies analyzing the impact of implicit bias in quality of care must be further funded to provide more precise, consistent, and updated findings pertaining to racial disparities.

Sources:

- https://www.vox.com/identities/2018/1/11/16879984/serena-williams-childbirth-scare-black-women

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5915910/

- https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/maternal-deaths/

- https://theundefeated.com/features/serena-williams-invests-in-project-aimed-at-improving-womens-maternal-health/

- https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/preventing-pregnancy-related-deaths.html

- https://www.catalyst.org/research/women-of-color-in-the-united-states/

- https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/disparities-pregnancy-related-deaths/infographic.html

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1047279703001285

- https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/data/maternal-morbidity-report-08-12.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4476314/

- https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163196#B2

- https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.119.012139

- https://www.verywellmind.com/implicit-bias-overview-4178401

- https://www.npr.org/2017/12/07/568948782/black-mothers-keep-dying-after-giving-birth-shalon-irvings-story-explains-why

- https://www.propublica.org/article/nothing-protects-black-women-from-dying-in-pregnancy-and-childbirth

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22239747/

- https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/how-we-fail-black-patients-pain

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1913086/

- Cover photo and illustrations created by Sara Kian