BY MADISON RAE | SQ ONLINE WRITER | SQ ONLINE (2017-18)

The beautiful beaches of San Diego and the rest of the Pacific ocean are facing significant threats from something man-made and nearly invisible: plastic pollution. Conservation groups inundate us with images of necks and fins trapped by soda rings, whales and dolphins tangled in discarded plastic fishing nets, and the colorful plastic contents of innumerable species’ stomachs. Images like the one above show sea turtles deceived by plastic, confusing bags and deflated balloons for their favorite food, jellyfish. The message that plastic is harming the ocean is clear, but just how desperate is the situation? According to several recent studies, the greatest danger may come from pieces of plastic that are much smaller than the usual debris you might find during a beach cleanup.

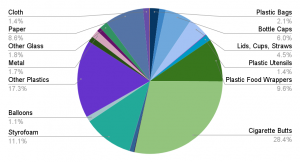

Over 60% of trash in the ocean, called marine debris, is composed of plastic. According to San Diego Coast Keeper, an organization that protects water sources in San Diego County, 54.5% of the trash collected from San Diego local beach cleanups in 2016 was plastic, especially small, Styrofoamâ„¢ based debris. When counted with cigarette butts, which have a plastic filter, plastic debris and cigarette remains make up 82.7% of the debris harming the San Diego coast.

A recent study led by researchers at Cornell University found that plastic debris is harming wildlife in other ways as well. Plastic traveling the ocean is a popular home for several types of bacteria that can seriously harm and cause disease in coral reefs. When those plastic items – often harmless-looking items like bottle caps and toothbrushes – scrape up against coral reefs, researchers believe that the contact introduces those harmful bacteria to the delicate coral. Coral with large spines or sections that jut out into the water had the highest levels of disease associated with the presence of plastic, as the farther the coral spreads into the water, the more likely it is to be scraped by plastic [1]. Reef health is already declining significantly with warming climates and changes in ocean pH and pollution. Additionally, corals infected with disease cannot regrow infected tissue, leaving sections of coral that succumb to disease stiff and skeletal, unable to provide for the coastal community of wildlife.

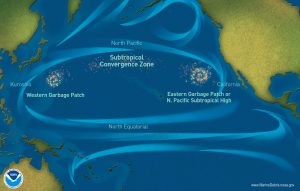

While there are no coral reefs as far north as San Diego, plastic is still a major problem in the Eastern Pacific. Many West Coast residents have heard about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, but not many people know why it exists or what it really looks like. It forms in a marine phenomenon called a gyre, an area where several ocean currents converge in a sprawling roundabout. There are several throughout the world’s oceans, and the Pacific Garbage Patch is caught in the North Pacific gyre spanning from western North America to east Asia.

Modern knowledge of these current systems comes primarily from an improvised study on global current systems conducted from the mid-1990s through at least 2011, when a cargo ship lost a container of 28,000 rubber ducks on the way to the U.S. from Hong Kong in 1992 [3]. Oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmeyer began documenting the toys’ travels through the world’s currents after they began washing up on shores all around the globe. Some found shore more quickly, but ducks in surprisingly good condition were still discovered upwards of 20 years after their unintentional release. Not only are the toys’ condition a testament to plastic’s inability to decompose, but researchers have also used the toys to map out a significant amount of the Earth’s current systems. The delay of many of the ducks’ arrival on shores can be contributed to being caught up in ocean gyres.

Because of the distance and shape of the North Pacific gyre, the Pacific Garbage Patch has sections of visible debris piled up together, but the largest and most harmful part of the Patch is nearly invisible microplastic. These tiny pieces move throughout the entire stretch of ocean ocean, floating on the surface or sinking into the sediment. There are even products that contain synthetically created microplastics called microbeads, which are too small to be caught by water filtration and can easily make their way into bodies of water. NOAA and other organizations are still studying the effects of microplastics on marine wildlife, as well as methods of removing them from different ecosystems. This study examined recent studies testing the impact of marine debris, and found that the vast majority of studies cited microplastic debris as the most harmful to marine life on the level of individual organisms, as well as cellular and molecular levels [11].

Currently, the most dramatic known effects occur throughout marine food chains. Large animals mistake objects like plastic bags for food, but small animals like plankton-eaters and shellfish often filter feed microplastics into their systems. Like larger animals, not only do they face slow starvation as indigestible plastic clogs their digestive systems, but the food chain as a whole also suffers. Chemicals found in different plastics can leech into the smaller creatures, which are then eaten by larger predators. In a similar process to mercury buildup, those chemicals and microplastic particles “stack” in the systems of larger creatures and can even make their way into humans.

A major issue in the plastic situation is “disposable” plastic products. Cheap, disposable bags, razors, etc. are sold for the sake of convenience, but will end up recycled or sent to a landfill to become microplastic. Fortunately, California is taking steps towards sustainability and attempting to combat plastic pollution by discontinuing the use of plastic bags in stores and discouraging plastic packaging. At UC San Diego, the Student Sustainability Collective has spent the past several years encouraging the use of reusable water bottles and bags, and attempting to end the sale of plastic water bottles on campus. Buying basics in bulk and storing them in reusable glass containers is a great plastic free option, but not always available. Several stores and products have sprung up offering everyday items that are recycled and compostable, but those products are often expensive and based in faraway cities. Some are beginning to offer shipping options free of plastic packaging, but they are still relatively difficult for the average person to access affordably.

Students and residents who want to minimize their impact on plastic pollution can start small; getting daily coffee in a reusable bottle to avoid plastic lids and straws, using reusable bags, recycling when possible, and avoiding buying items with excessive plastic packaging can be good first steps for a more sustainable lifestyle.

Plastic is an incredibly useful and common product in modern society. It makes our lives infinitely more convenient, but the effects of such widespread plastic use are coming back to haunt humanity. Washed out to sea and returning to the shore or through the food chain, scientists are just beginning to discover the toll plastic is creating on marine ecosystems. It will break down to nearly invisible size, but used plastic is not gone and should not be forgotten.

[hr gap=”0″]

Sources:

[1] http://science.sciencemag.org/content/359/6374/460.full

[2] https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/01/180125140848.htm

[4]http://www.sdcoastkeeper.org/learn/fishable/marine-debris/data-from-san-diego-beach-cleanups

[5] http://www.sdcoastkeeper.org/learn/fishable/marine-debris/types-of-beach-pollution

[6] https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/microplastics.html

[7] https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/ocean-gyre/

[8] http://www.sdcoastkeeper.org/about-us/our-story

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friendly_Floatees

[10] https://www.wired.com/2011/03/sea-turtle-plastic/

[11] https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c58b/07955f6b6f8cde16472e3bdfd15319af4770.pdf

Images:

http://sustyvibes.com/sea-creatures-may-eating-plastic-tastes-delicious/

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/does-proliferation-microplastic-pollution-from-aka-concern-gaertner

https://marinedebris.noaa.gov/info/patch.html

http://www.sdcoastkeeper.org/learn/fishable/marine-debris/data-from-san-diego-beach-cleanups