Since 2014, the American Society for Microbiology has hosted Agar Art, an annual competition accepting submissions by petri dish rather than canvas. Every year, scientists and artists together embark on a quest to create paintings with a rather unorthodox material: microbes.

These tiny organisms—bacteria, yeast, and more—are often invisible to our eyes in individual numbers, yet they are found almost everywhere—from the bottom of the ocean to our own tongues. However, this living medium often has a mind of its own. How do microbe enthusiasts join forces with their tiny collaborators to craft works of art?

One of the first microbe-painters was scientist Alexander Fleming. Much before he brought the live-saving, antibiotic fungus called penicillin into medicinal practices, he was a watercolor painter. This love for art translated to his lab, and he used different natural pigments to stain different species of bacteria as he shifted them around to create images of houses, ballerinas, and more.

Following in Fleming’s Footsteps

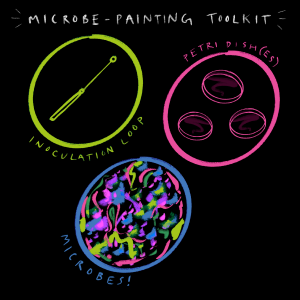

Mirroring Fleming’s process, microbe artists today turn to agar, a jelly-like substance derived from algae that allows bacteria to flourish, as their primary canvas. They might use naturally-purple bacteria, bright-red yeast cells, or the bioluminescent bacteria A. fischeri to add glow. Some plate-painters even infuse bacteria with fluorescent proteins, transforming the bacteria to shine colors outside their natural spectrum. “Painting” with microbes can be difficult due to their sporadic growing times and diverse life cycles. Timing is crucial—some microbes may grow faster than others, and others may perish earlier and leave behind a dull agar canvas rather than a colorful microbe colony.

However, with knowledge and guidance from scientists and experts, artists can nurture different microbial species to grow along desired paths by using long, thin tools called inoculation loops. The final painted plates are sealed with epoxy, so that the microbes can’t escape, and then photographed to capture their progressive growth—living art such as this may change in appearance even within a few hours.

While the Agar Art competition happens only once a year, microbial painting has become a year-round passion for many and brings the beauty of microbes out of the lab and into the view of broader audiences. Rather than trying to combat the natural patterns of microbe growth, artists can rely on this living medium to contribute a unique unpredictability to their canvases.

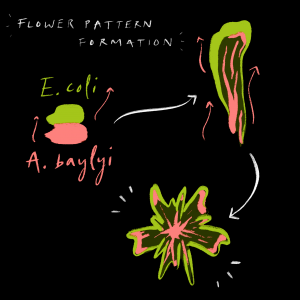

Film Flowers

Even without a human hand guiding their path, microbes often create intricate patterns as they grow. Sometimes, all it takes is mixing two species of bacteria in the same petri dish to set off a flurry of physical interactions that drive interesting petri-dish designs. For example, scientists found that when E. coli and A. baylyi bacteria interact, their different levels of stickiness to the agar cause them to push against one another and form flower patterns on the plate. Turns out, these tiny designs can help scientists understand how to tackle bigger problems.

This flower pattern is one example of a biofilm, which forms when one or more species of microorganism grow together. Biofilms are found everywhere—hydrothermal vents in the ocean’s depths, showers and pipes throughout our cities, and even in our large intestines and plaque on our teeth. These microorganism collections aren’t inherently good or bad. Instead, their function and effects vary based on the environments they grow in. However, in the specific case of infections, understanding the details of biofilm growth can help scientists figure out how to disrupt microbe activity through treatment plans.

From flower patterns to Agar Art to Fleming’s original petri-dish paintings, creativity persists in the interface between the human and microbial worlds. Paying attention to the natural patterns of life can inspire new perspectives on traditional processes, like those of creating a painting or conducting a scientific experiment.

As time passes, we continue to learn about our relationships with microbes in terms of our health and everyday lives. These microscopic organisms inspire scientists and artists alike to construct knowledge, harness creativity, and explore the invisible.

Check out some microbe art!

- https://www.asm.org/Events/2019-ASM-Agar-Art-Contest/Previous-Submissions

- http://www.microbialart.com/

- https://www.bacterialart.com/

- http://www.sciencetothepowerofart.com/

Illustrations by Arya Natarajan