BY MADISON RAE | SQ ONLINE WRITER | SQ ONLINE (2017-18)

The middle of April 2018 saw major news headlines filled with panic-inducing warnings about contaminated romaine lettuce. Reports of hospitalizations, kidney failure and even death circulated; yet, there were no recalls. The source was narrowed down to the Yuma, Arizona area, but even today a more specific contamination source has not been found. We may finally be safe to eat lettuce again, but how did this outbreak get so bad? Why can’t the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tell us exactly what happened? How safe is our food, really?

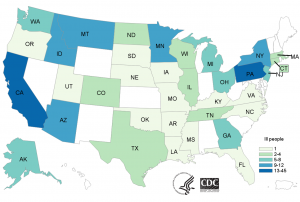

We still don’t know what aspects of the romaine were compromised; no single processing plant or growing farm has been the conclusive source. The reason we’ve been given the “all clear” now is that Yuma stopped distributing lettuce on April 16th, and the 21-day shelf-life of that lettuce is now over; however, new cases may have appeared for up to 2 weeks after the declaration of safety. This short shelf life is good for salad lovers, but makes it incredibly difficult to trace infected lettuce; any uneaten, infected lettuce is likely now in the trash and unusable to the FDA and CDC in their efforts to trace the tainted romaine’s production path. As of now, the official counts for this outbreak are 197 infected and 5 dead across 35 different states, with California and Pennsylvania having the most infected citizens (45 and 24 respectively).

This strain of E. coli, called O157:H7, is particularly dangerous because it can create Shiga toxins. These biological toxins can cause dysentery and inhibit protein synthesis in some cells, eventually damaging the intestines and kidneys. There is a chance of hemolytic uremic syndrome, which can cause kidney failure and even death if untreated. This is a very unpleasant strain with a higher hospitalization rate, and according to the CDC, there has been an outbreak of O157:H7 every single year since 2006 in foods – ranging from leafy greens, to nuts, to meat products. This was not even the first O157:H7 outbreak of 2018. Normal strains and Shiga toxin- causing E. coli (STEC) are both found in the intestinal tracts of animals like cows who ferment plants in their stomachs, as well as chicken and deer. Outbreaks can occur when the meat is infected with bacteria from the intestinal tracts, or when feces or particles are spread to nearby farms and infect produce.

Several outbreaks of O157:H7 have started at county fairs, where particles of infected fecal matter travel through the dust in the air and settle on food, cooking surfaces, other surfaces that people may touch before eating, or are inhaled by passerby. When swabbing an Ohio fair in 2002 after an O157:H7 outbreak, E. coli was found over 15 feet off the ground, on walls and rafters. Well-timed hand washing may have saved some fair-goers, but in the case of leafy greens, washing just isn’t enough. Greens like romaine are covered in tiny crevices that are easy for E. coli to settle into, and no amount of washing can remove all of the bacteria. The only way to ensure the romaine is safe would be to boil it, which is no way to enjoy a salad.

Why wasn’t there a recall? Most food recalls are voluntarily performed by companies aware of a potential safety issue. Requested recalls are “reserved for urgent situations” according to the Code of Federal Regulations. The FDA also doesn’t often publicly announce recalls or food safety issues, unless there is a serious issue. While there is a weekly FDA Enforcement Report that shows all current recalls, most of them do not develop into the media spectacle that we saw for romaine. Because the FDA was unable to pinpoint the definitive source of the outbreak, there was no way to instigate a recall. A few grocery stores placed voluntary recalls on romaine products out of caution, but without knowing a specific grower, supplier, or distributor to watch for, all the FDA could do was issue a public safety warning.

In contrast, in the midst of this romaine outbreak, Rose Acre Farms in Indiana issued a recall for eggs during a concurrent multistate salmonella outbreak. The farm was the only source found, and at least 35 people were infected and 11 hospitalized, but stores across several Midwestern and Southern states were able to pull products off shelves before the disease spread further. Ultimately, as panic-inducing as these news reports and recalls may be, there are agencies in place doing their best to keep us safe. Outbreaks of foodborne illness are happening more often than we think, albeit on a smaller scale than the more rare multi-state outbreaks. Whether this newfound knowledge is strangely comforting or deeply troubling is up to you. Salad lovers, stay safe out there.

[hr gap=”0″]

Sources:

https://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/outbreaks.html

https://about-ecoli.com/ecoli_transmission

https://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/2018/o157h7-04-18/map.html

https://about-ecoli.com/ecoli_outbreaks/news/tests-suggest-e-coli-spread-through-air

https://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/general/index.html

https://www.fda.gov/Food/RecallsOutbreaksEmergencies/Outbreaks/ucm604254.htm

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4270005/

https://www.fda.gov/Food/RecallsOutbreaksEmergencies/Outbreaks/ucm604254.htm

https://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm049070.htm

https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfCFR/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=7&showFR=1

http://www.businessinsider.com/can-you-wash-e-coli-off-romaine-lettuce-2018-4