By Sharada Saraf | SQ Online Reporter | SQ Online (2016-2017)

________________________________________________________________________________________

Older siblings have the unfortunate experience of younger siblings barging into their rooms, making a mess, then disappearing while laughing diabolically. As an older sibling myself, my little brother would do this so often that I eventually insisted on having a lock on my door. Once installed, my brother’s destructive actions were easily preventable, and he was left screeching and fruitlessly banging on the door, then sliding down to the floor helplessly outside. Obviously, I preferred this dramatic display to the earlier chases I would have to embark on in order to prevent my brother from entering my room.

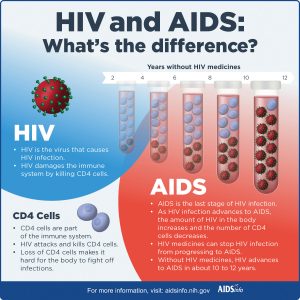

Like shutting and locking the door to prevent annoying younger siblings from making a mess in your space, a new method developed by scientists at the Scripps Research Institute have antibodies functioning in a similar way in order to block human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from infecting cells. In mainstream HIV therapies, antibodies administered to patients float freely in the bloodstream; however, similar to the effectiveness of locking your room rather than angrily pursuing your sibling, the Scripps method allows antibodies to directly be tethered to the immune cells’ surface, disallowing the virus to access cell receptors and multiplying throughout the body. Incredibly, the possibility of creating a cell population entirely resistant to the virus is now a tangible reality, and with it the possibility of creating a more potent, medication-free therapy for AIDS patients.

Jia Xe, a senior staff scientist at Scripps, calls this “the neighbor effect”: the method of having one antibody stuck to a cell, which is more effective than free floating antibodies, and may potentially lead to controlling HIV in AIDS patients without the use of medication.

Before testing this method with HIV, the scientists first used rhinovirus, which is responsible for many cases of the common cold. Using a vector called lentivirus, a new gene was delivered that instructed cultured human cells to synthesize antibodies that bind with the cell receptor, one the rhinovirus needs available in order to enter the cell and spread infection. With the antibodies blocking that site, the rhinovirus was unable to enter the cell, and therefore unable to infect the cultured human cells.

While this model has the potential to be transferred over to many other types of viruses, the researchers chose to use this technique with HIV, because it is known that all strains of the virus need to bind with a cell surface receptor called CD4. Study senior author Richard Lerner says that their use of this technique on the antibodies responsible for protecting the receptors was successful, and the researchers created an HIV-resistant population. The antibodies targeted the CD4 binding site and prevented HIV from infecting immune cells, thus preventing further infection.

The implications of this study on AIDS patients is incalculable; this HIV “vaccine” has the potential to remove existing therapies and replace it with a far more lasting treatment. Current treatments often prove grueling for the patient: antiretroviral therapy, for instance, requires taking a combination of HIV medications in order to slow the progress of the virus. Years of work are still required to test the Scripps method on people, but if it is successful, it would not only control the virus – it would cure patients of AIDS entirely. The Scripps method has opened up an entirely new platform in treating viral diseases; it has opened the door for discovery of further viruses that can be treated with antibody therapies, and puts scientists one step closer to finding ways to fortify our immune systems.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hWFj-K07xb0&w=620&h=350]

In mainstream HIV therapies, antibodies administered to patients float freely in the bloodstream; however, similar to the effectiveness of locking your room rather than angrily pursuing your sibling, the Scripps method allows antibodies to directly be tethered to the immune cells’ surface, disallowing the virus to access cell receptors and multiplying throughout the body.

[hr gap=”10″]

Sources:

https://www.scripps.edu/news/press/2017/20170410lerner.html

http://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/business/biotech/sd-me-hiv-lerner-201704010-story.html

http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/new-approach-makes-cells-resistant-to-hiv-300437412.html