The Olympics remain the great international showcase of harmonious athleticism and nationalistic pride, and this past February’s Winter Olympics in Beijing was no exception. Such a big competition sparks many news and controversies, one of which was Kamila Valieva’s figure skating doping case. The 15-year-old Russian figure skater tested positive for trimetazidine, a drug that is banned from the Olympics for increasing blood flow efficiency and improving endurance. Her lawyers argued that Kamila accidentally ingested the drug through contamination of a product by the heart medication her grandfather was taking.

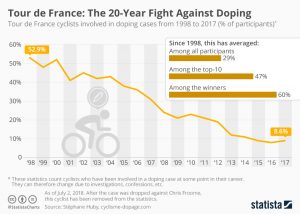

Disregarding the intentions of the drug use, this case adds to the numerous instances where performance-enhancing drugs have caused major scandals in athletics. The American College of Medical Toxicology defines doping as “the use of prohibited medications, drugs, or treatments by athletes with the intention of improving athletic performance,” and it has been around for centuries. In fact, Valieva’s case wasn’t the first time trimetazidine made an appearance in the Olympics; Russian bobsledder Nadezhda Sergeeva tested positive for it in 2018s, four years after Chinese swimmer Sun Yang’s case. Hundreds of other Olympians spanning many countries have been involved in doping scandals, but these offenses aren’t just confined to the Olympics. The Tour de France, an annual men’s bicycle race, has been plagued with allegations and cases of doping for decades, the most notable being Lance Armstrong. The seven-time Tour de France champion was stripped of his titles and banned from Olympic sports after it was revealed that he used and even encouraged his teammates to use performance-enhancing drugs.

But if doping has been known to end countless professional careers, why do athletes continue to take the risk? Simply put, athletes dope in order to win. Sports, in general, reward excellence, and for professional athletes, the reward of being considered the best is the pinnacle of achievement. As Dr. Michael W. Austin states, “athletic excellence as it is conventionally understood, without moral excellence, has very little value.” This display of excellence is solely measured by an athlete’s physical skill, so when someone regards their natural skill as lacking, they turn to performance-enhancing drugs.

This combination of personal achievement and patriotic nationalism breeds a toxic environment that pushes some athletes to seek that upper hand; Carlos D’Angelo’s and Claudio Tamburrini’s article in the Journal of Medical Ethics brings up some sports have become the center attractions for countries, such as American football or Canadian hockey, so the addiction to doping is “the behavioral reaction sportspersons adopt to deal with the hard demands of the sports market as well as with…misplaced sports nationalism” and would be the only way to alleviate their stress.

But what exactly is the science behind doping? The idea of injecting DNA and hormones into a person’s body for either enhancing athletic performance or gene therapy isn’t a new idea and has been researched extensively. Professor H. Lee Sweeney at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine has garnered many requests for doping from athletes due to his innovative discovery—reversing muscle degeneration caused by genetic disorders. Sweeney and his colleagues found that when a protein called insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) came in contact with cells outside of muscle fibers, those cells would grow. They tested this on mice that had a mutation causing loss of muscle function; when exposed to IGF-1, their muscle mass increased by about 40%. Although promising, the effects on these “Schwarzenegger mice” have yet to be tested on patients or other humans.

Professor Sweeney isn’t the only one who has provided extensive research into doping. A group of scientists in La Jolla’s very own Salk Institute examined that injecting mice with a gene that contains a fat-burning protein called PPAR-δ let them run up to twice the distance of regular mice. Ronald Evans, the head of the group of scientists, expressed that his purpose for pursuing this line of research was for the prospect of therapeutic value, not athletic exploitation. If PPAR-δ expression were to be increased in humans, it could increase type 1 muscle fibers (fibers that support long-distance endurance activities with less fatigue), therefore increasing protection against obesity and type II diabetes.

Doping is unpredictable, which is why Sweeney, Evans, and other researchers who have publicized these substances that could be exploited have stressed how experimental and early their results are, for they need to be proven safe on larger animal models before testing on humans. According to the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM), doping could have harmful and long-lasting side effects on a human’s cardiovascular, respiratory, hormonal, and central nervous systems, to name a few. Some of the popular performance-enhancing drugs include anabolic steroids, growth hormones, and direct blood doping.

Anabolic steroids, most commonly used in sports that require explosive power such as boxing or lifting, increase strength and muscle mass by increasing protein synthesis within cells, which results in more cellular tissues in the muscles. However, excessive or long-term use of anabolic steroids could harmfully affect cholesterol levels, acne, high blood pressure, liver damage, and changes in the structure of the left ventricle of the heart.

Human growth hormones (hGH) have an anabolic effect improving muscle mass and performance. It is a naturally occurring peptide hormone, but athletes and bodybuilders who take these hormones claim that they increase lean body mass and carbohydrate and fat metabolism and decrease fat mass. In adolescence, hGhs promote height growth to lengthen our limbs to adult proportions. The hormone sends signals to our liver to make insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), which is involved in bone growth. In adults, it then maintains body structure and metabolism by regulating blood glucose levels. Synthetic growth hormones can only be administered through injection, but there is a risk of cross-infection through contaminated needles, as well as osteoporosis, impotence, and cardiovascular diseases, among others.

Blood doping increases the amount of hemoglobin, an oxygen-carrying protein in the blood, which allows higher amounts of oxygen to fuel an athlete’s muscles. Blood doping is usually in the form of blood transfusions, like when a patient needs more blood to replace those lost in an injury or surgery or injections of hormones and chemicals. Blood doping causes the blood to thicken, so it poses a high risk of causing blood clots, heart attacks, and strokes, as well as dangerous buildups of iron in the body, and is most commonly used in endurance and stamina sports such as long-distance running.

With such intense side effects, steroids are actually beneficial in medical areas if used and proportioned correctly. Testosterone, produced from anabolic steroids, improves bone mineral density and muscle strength, which can be beneficial for those with bone or muscle-related complications. They also help in the treatment of chronic diseases’ post-operative recovery. Human growth hormones are also prescribed for both childhood and adulthood hGH deficiency and for girls with Turner’s syndrome, where one of the X chromosomes is partially or fully missing, as well as relief from excessive burns or other thermal injuries.

Steroids and hormones are also administered in a medical setting to transgender people during their transition. Many seek hormone therapy in transitioning, where testosterone is used in transgender men to suppress biologically female characteristics and estrogen is used to help develop those characteristics. Hormone therapy is also used in treating certain types of cancer, where the drug stops or slows the production of certain natural hormones that usually feeds the affected tissues and cancer. For example, tamoxifen is a drug prescribed for patients with breast cancer, as it is a drug that blocks receptors on breast cancer cells so estrogen cannot bind to them.

Despite years of regulations and cases, it is still hard to determine the ethicality of drug use in sports. The Hastings Center Report remarks that some human traits are learned through practice and pain, but much of it is “the result of unequal genetic endowment,” but because the “genetic lottery” is not something humans can control, we don’t consider it unfair. So what can we consider fair and unfair? We can’t go off the basis of “natural” versus “unnatural,” as we have learned that testosterone and growth hormones are naturally produced by the body yet are still banned. And is it the job of an athlete to be a role model? Willie Wilson of the Kansas City Royals argued that he “never intended or agreed to be a role model, only a baseball player” after he received a harsh penalty, a prison sentence, for acting as a middle man in a drug deal.

In the 1972 Olympics, Rick DeMont had to give up his gold medal in long-distance swimming when his antiasthmatic medication was found to have a prohibited substance, ephedrine. Regardless of his intentions, DeMont was stripped of his medal to prevent an athlete from gaining an unfair advantage, but should regulations on an athlete’s medication still be held as tight, or should there be an asterisk? According to the Hastings Center Report, Rick DeMont was scapegoated in the case of doping, “not for doing anything immoral, but so we can remind ourselves of our purity, our goodness, and perhaps our homogeneity.” In quickly associating and condemning drugs and substance use to feel like we are preserving the “golden” reputation of sports, society taints the reputation of the role drugs plays in a changing population and overlooks the “good” that it brings, such as the promises of gene therapy for disabilities or curing cancer.

Sources:

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/what-is-the-drug-behind-russias-olympic-doping-case

https://www.history.com/news/doping-scandals-through-history-list

https://www.tspain.com/blog/tour-de-france-and-performance-enhancing-drugs

https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/video/armstrongs-doping-downfall

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/chemistry/anabolic-steroid

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305894/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1517/13543784.2011.544651

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5182227/

https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/co