By now, it’s likely you’ve either tried or at least heard of one of the many dieting strategies that are out there. Fundamentally, dieting is understood in terms of caloric input and output–maintaining a caloric deficit between the energy our bodies use and our daily food intake.

In recent years, we’ve come to understand that effective dieting isn’t just about how much you eat but more so what you eat. One popular diet limits the body’s intake of carbohydrates to initiate a process called ketosis, which burns fat at a faster rate–but more on that later. The average adult on a caloric-cutting diet needs to burn 500 more calories than they consume per day to lose four pounds of fat in a month; however, with a regimented ketogenic diet, the average adult can expect to lose ten pounds every month by carefully watching the types of foods they consume.

When I asked my doctor about dieting, he suggested a current approach to losing weight called intermittent fasting. This process consists of fasting at different time intervals during the day. As it turns out, when you eat also plays a significant role in weight loss and in improving overall health. As such, intermittent fasting provides several benefits over food-selective diets, such as the ketogenic diet. For starters, embarking on a ketogenic diet requires drastic lifestyle change, as it can be difficult to alter eating habits you’ve had your whole life. Additionally, the ketogenic diet doesn’t have the same effect on everyone; although it is highly beneficial for some–this diet has even slowed down the spread of diabetes–many have reported negative side-effects such as headaches, fatigue, and poor sleep. On the other hand, although intermittent fasting can be challenging, doctors have been recommending the practice because it allows patients to reap immense health benefits without completely overhauling their eating preferences and with minimal side-effects.

Interestingly enough, if I were to go back in time to 460 B.C. and ask a Greek doctor for dieting advice, they too would argue in favor of intermittent fasting. As Hippocrates once said:

“The natural healing force within each one of us is the greatest force in getting well. Our food should be our medicine. Our medicine should be our food. But to eat when you are sick is to feed your sickness.”

The ancient Greeks believed nature was the most powerful healing force in the cosmos. To them, the human body was sacred and divine, innately possessing supernatural methods of healing. Hippocrates famously referred to fasting as the “physician within;” however, as the Greeks did with many ideas, they left us more theories than explanations for this phenomenon.

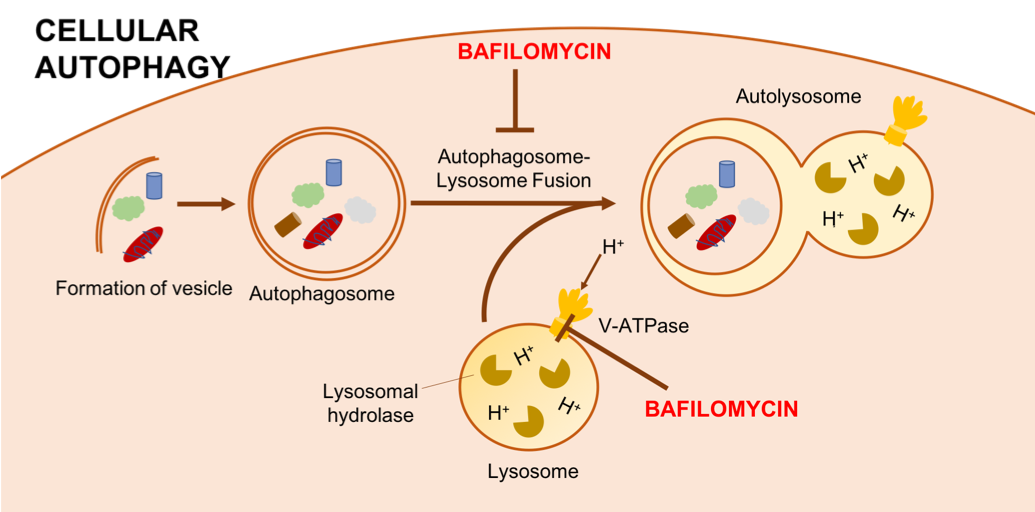

Thus, the mystery of the physician within was not understood until the late 1980s, when a Japanese researcher observed how vacuoles, which are large, sac-like structures that store cellular waste, responded to starvation in mutated yeast cells. Under his electron microscope, the young researcher Yoshinori Ohsumi observed the process of autophagy, or the cell’s method of consuming its own proteins to meet energy requirements during starvation.

Within thirty minutes of starving the yeast cells, Ohsumi observed the formation of small spherical structures that degraded various intracellular components such as harmful proteins, organelles, and enzymes in response to starvation-induced stress. He named these structures autophagosomes.

Since his discovery in 1988, Ohsumi has worked to elucidate the mechanism of the physician within. Uncovering the link between fasting and health culminated in him winning the 2016 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for characterizing the cellular pathways of autophagy. Ohsumi discovered that fasting induces cells to switch on autophagy-related mechanisms, roping in a variety of cellular components to recycle for energy and other cellular processes.

Autophagy is a non-selective process that is regularly used to recycle misfolded proteins, damaged organelles, dangerous bacteria, and other abnormal components during cellular checkpoints. Autophagy is vital for cell homeostasis, and its absence leads to abnormal cell growth, shortened cell survival, and increased cell susceptibility to disease. As we age, the rate of autophagy in our cells vastly diminishes, leading to unchecked cell cycle checkpoints and therefore increasing the chances of cells spiraling into disease. Thus, for older individuals, fasting is a great way to revive autophagy levels and recycle cellular components that may otherwise cause disease.

Recent research has also revealed that autophagy selectively removes specific proteins that are known to moderate a variety of diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease. In Parkinson’s, autophagy degrades ð°-synuclein and PINK1-PARKIN, both of which are known to promote a diseased state. Similarly, autophagy removes proteins and oncoproteins that cause other diseases such as Alzheimer’s and cancer. Due to autophagy’s role in regulating tumor suppressive genes and oncoproteins in many cancers, researchers are studying autophagy treatment as a potential therapy for cancer patients.

On top of being used for temporary treatment, fasting can be a game-changer while we work to find the cure for illnesses like cancer, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. While in many cases these diseases can only be slowed down rather than stopped, delaying the onset of the disease could help protect quality of life.

What is the best way to benefit from autophagy? Research has shown that autophagy kicks in after 12-16 hours of continuous fasting. There are many different methods to reach 12-16 hours of fasting, and intermittent fasters choose a method depending upon their eating preferences.

The 16/8 method involves fasting everyday for 16 hours and eating a restricted diet during the remaining 8 hours of the day. If you’re a breakfast-skipper, this method is ideal, as it can be achieved by simply skipping dinner and breakfast. While 16/8 may be the easiest fasting method, it comes with its own drawbacks. Inducing autophagy everyday may not be good for the body’s metabolism. Furthermore, 16 hours of fasting is just enough to initiate autophagy in many individuals. Therefore, a longer fasting period may be necessary to reap substantial benefits.

The 5:2 diet is an intermittent fasting strategy more appropriate to beginner fasters, but has been shown to be an effective weight-loss strategy while maintaining lean muscle mass. In this dieting strategy, one may eat normally during five days of the week and restrict daily caloric intake to 500 calories during the remaining two days of the week. This provides cells with a minimal intake of energy, forcing them to supply the rest through autophagy.

Before attempting more intense methods of fasting, it is important to consult your doctor and become comfortable with fasting on regular, smaller intervals. Once your body is used to fasting, full 24-hour fasts a couple times a week may be used to “cleanse” the body, which seems to have the most anti-aging and autophagy-inducing effects out of the different diet strategies, according to recent studies.

While interventive treatment of many diseases still remains limited, our bodies provide an immensely beneficial, innate way of healing through autophagy. Autophagy is a human mechanism evolved for us to take advantage of the physician within.

References:

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/weight-loss/in-depth/weight-loss/art-20047752#:~:text=Generally%20to%20lose%201%20to,least%20for%20an%20initial%20goal.

- http://www.greekmedicine.net/hygiene/Fasting_and_Purification.html

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2016/ohsumi/biographical/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/emm201210#ref-CR10

- https://www.healthline.com/health/autophagy#benefits

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3312403/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5039008/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20724820/

- https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/6/1234

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30475957/