In the world before COVID-19, I would walk to the on-campus dining hall Roots and do what I love most when I’m in the Muir area: people-watch. Folks would grab a Polar Bear hot latte from the Middle of Muir coffee shop and seat themselves either on the patio or the grassy area near John’s Market. From the wide windows of Roots, I’d quietly observe unique fashion, snippets of bilingual play-by-plays, and heads buried in books.

During my time on campus, I wasn’t able to meet third year Kyla Laing at Roots, but between our shared love of books and her vegan diet, I think it’s likely that she would have been one of the passersby. If we had been able to meet in person and gotten to know one another better, I’d eventually ask her the question:

“What made you go vegan?”

The answer would not be so simple. Kyla was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in her freshman year of high school. Autoimmune diseases like SLE lead to tissue damage and systemic inflammation because the body’s immune system mistakes its own tissue as foreign and attacks it. For Kyla, her kidney was targeted and attacked by her immune system, causing severe inflammation and significant organ failure, the defining characteristic of Stage 4 Kidney Disease. In addition to the hospitalization and medication she received during treatment, she transitioned from a vegetarian to vegan diet in order to improve her health.

So why go vegan? Kyla had heard other patients’ testimonies that changing one’s diet had helped their SLE symptoms, and since her household was already vegetarian, it was an easy dietary switch. As you look closer into veganism, you can see its range of beneficial effects on the body. For starters, going vegan may help reduce inflammation, one of the hallmarks of SLE. People with vegan diets avoid the intake of proinflammatory molecules found in red meats while eating lots of whole plant foods with anti-inflammatory nutrients.

Additionally, your diet affects the microbiome that lives inside your intestines, and as a result no two people’s microbiomes are the same. The human microbiome is the unique population of bacteria, viruses, and microbes that lives within our bodies and have a host of beneficial outcomes for our health, including protecting us against pathogens and bolstering our metabolism. However, there are some situations where microbiome-influenced metabolism has negative consequences for meat-eating people.

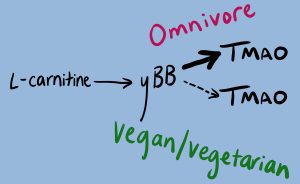

For example, TMAO is a molecule that causes an increased risk for heart failure, stroke, and chronic kidney disease. TMAO is an end product of L-carnitine metabolism, and this metabolism is completed by your gut microbiome. If you are an omnivore, your gut microbiome will generate high levels of TMAO. On the other hand, if your gut microbiome reflects that of a vegetarian or vegan diet, the metabolism of L-carnitine will end early and you will neither produce TMAO nor the negative side effects it boasts.

While there is no cure for SLE, we can see the direct effects a vegan diet has on inflammation and kidney disease, as evidenced by Kyla’s experience with SLE. Through various lifestyle changes communicated to her doctor, Kyla has made immense progress by increasing her kidney function, dropping from five intense medications to two, and participating in the physical activities that she loves, like running.

However, remission, or the period of time when symptoms subside, does not mean that all of SLE’s intricacies have been fully addressed. During remission, a person with SLE will experience what is colloquially known as an invisible illness. A person with an invisible illness may struggle with a diverse host of symptoms that may not be physically apparent to people around them.

What do the symptoms of an invisible illness look like? For Kyla, staying still for too long, especially with online classes, creates persistent joint pain in her wrists, legs, and back. During the week, waves of fatigue cause everyday tasks to become arduous. Additionally, she takes medication to limit her overactive immune response which would normally attack her body’s own tissues; however, with a subdued immune system, Kyla often becomes sick with common colds and is at risk for life-threatening diseases like COVID-19.

Because the challenges people face with chronic illness are invisible by nature, peers and colleagues can misinterpret one’s actions. Kyla explains that she will sometimes need to cancel plans with friends because her symptoms have become overwhelming, and for friends who don’t know about SLE, this sudden cancellation might be taken the wrong way.

A person with a chronic illness may feel obligated to explain their situation in order to avoid judgment and false perceptions, as well as secure the accommodations they might need. The responsibility of revealing one’s own medical history then falls on the person with the invisible illness, even though this kind of admission is not required from the rest of the able-bodied community.

In high school, Kyla says that she didn’t run into this problem as much, since some of her friends had been there through her remission. But coming to UC San Diego and meeting new friends presented a new issue. When is she supposed to reveal that she has SLE? And how? Kyla figured out that the question “What made you go vegan?” is a good enough segway to introduce her chronic illness.

But in the professional scene involving both employers and professors, it becomes more difficult. “There are certain contexts where you walk in and you want people to respect you,” Kyla says. “Sometimes [invisibility is] nice because… someone doesn’t have the opportunity to judge me for the illness I have.”

In the United States, workers are able to self-identify their disability or chronic illness to their employer. However, there is a disparaging lack of self-identification due to the concerns regarding workplace discrimination, limited job responsibilities, a focus on health status over work performance, and job termination.

The preference of invisibility over illness-related discrimination has its caveats, however. Revealing this part of herself sometimes becomes necessary, as her symptoms still impact her greatly. If Kyla chooses not to tell someone about her chronic illness, she explains that there are “times where symptoms are impacting my life [that] week, and I don’t feel comfortable bringing [SLE] up out of nowhere,” she says. “It becomes tricky when you no longer want it to be invisible.”

Managing symptoms alongside the stresses of university can be difficult, especially when the weight of disclosing this information falls on to the person with a chronic illness. However, it’s arguably even harder to have to validate one’s own invisible symptoms. Kyla explains, “You’re in a [university] environment where everyone is stressed, everyone is tired. You don’t feel like you’re feeling anything different than them.” For her, there’s no scale to measure her fatigue and pain. “[I] end up belittling my own symptoms. No one can see it, so no one else is validating you.”

Validating one’s struggles with health is a long and difficult journey. As an able-bodied person myself, I haven’t had to do such self-reflection on my own body. I haven’t had to decide when and where I needed to share my medical history in order to get the accommodations I need and validate my experience to others. Conversations regarding invisible illness need to start with addressing my own privilege as an able-bodied person before moving out into the community on campus and in the workplace. I’m coming to realize that the question “What made you go vegan?” bears a much larger legacy in both scientific research and the criticisms of our society. The more we make space for this conversation, the less these systemic issues will remain invisible.

Kyla Laing gave permission to display her real identity in order to shed light on SLE and how it has affected her experience at UC San Diego. If you would like to share your own experience with chronic illness, disease or disability, please feel free to reach out to akifer@ucsd.edu. And to Kyla, thank you for sharing your story and shedding light on how invisible illness affects students.

If you are interested in learning more about SLE, the previous blog of this series discussed the nuances of living with a chronic disease during COVID-19.

______________________________________________________________

Sources:

- https://www.cdc.gov/lupus/facts/detailed.html

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/how-to-use-food-to-help-your-body-fight-inflammation/art-20457586

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4290017/

- https://www.clevelandheartlab.com/blog/the-gut-the-heart-and-tmao/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6213249/

- https://invisibledisabilities.org

- https://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/addressing-the-date-gap-in-disability-employment.aspx

- https://sqonline.ucsd.edu/2020/11/living-with-the-chronic-disease-sle-during-covid-19/

Image Sources:

- https://unsplash.com/photos/RSSOtpmRySU?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditShareLink

- https://unsplash.com/photos/-gOUx23DNks

- https://unsplash.com/photos/ZPTduQKik6c

- https://unsplash.com/photos/RA5ntyyDHlw

- https://unsplash.com/photos/uwpo02K55zw

Featured Image and TMAO metabolism diagram were taken/drawn by Staff Writer Allison Kifer.