I don’t know about you, but I for one am a big fan of FD&C red color #40, hydrolyzed corn protein, tBHQ, Dimethylpolysiloxane, along with some ferrous gluconate for good measure. And no, I know what you’re thinking–this isn’t a list of the various compounds I decided to taste during chemistry lab. In fact, these are just a small part of a laundry list of ingredients that go into making a delicious Goody’s burrito bowl. Surprised? I certainly was, but this discovery only added to my already complicated relationship with dining hall food.

HDH food can be the bane of one’s existence, especially when you realize it’s your fifth consecutive day eating Pines chicken tenders (not speaking from personal experience or anything). At the same time, the greasy meals can be a source of comfort during finals week, when one decides to drown their sorrows in the oil reserve known as OVT pizza, which somehow never fails to provide a hit of dopamine. This is a pretty strange dichotomy, yet most of us don’t tend to question dining hall food too much. Instead, we resort to burying our stress in a plate of undercooked rice and veggies from 64 Degrees. Shortly after comes the freshman 15, followed by the sophomore 60, and possibly the senior 75, and the whole time we’re left wondering–why? And how? But what I discovered recently is that it might not be how much you’re eating, but rather what you’re eating.

Let’s start our culinary exploration with Pines–one of the most popular dining halls (for reasons I cannot seem to wrap my head around). Look to your right as you enter, and you’ll see a group of freshmen rapidly slurping down what appears to be a relatively innocuous vegan meal–tofu, vegetables, and udon noodles. But what we don’t see is that immediately after these freshmen return to their rooms, they experience a massive headache, strange stomach sensations, and instantly oily skin.

There could be a number of causes. After all, everyone’s body has a different sensitivity to different ingredients. But one suspect ingredient is the stir fry marinade, which is chock full of high fructose corn syrup. High fructose corn syrup is responsible for that sweet and salty balance to the flavors that dance around on our tongues when we take our first slurp of the udon, but it is sometimes known as the Darth Vader of nutrition–demonized and slightly misunderstood.

Some studies support the idea that high fructose corn syrup has an epigenetic potential, putting one at increased risk for metabolic syndrome–a term referring to a host of diseases that increases overall morbidity (think heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, etc). However, this may not accurately represent the full picture. High fructose corn syrup is nutritionally identical and structurally similar to sucrose, as both are made from the synthesis of glucose and fructose. When broken down, both are rapidly absorbed by the bloodstream and increase our risk for metabolic syndrome, making it unfair to simply demonize high fructose corn syrup when sugar’s effects are just as bad (1).

Ok. So I found high fructose corn syrup–AKA sugar–in my noodles. What’s the big deal? Aside from the fact that one serving of udon noodles had 15 grams of sugar (â…— of a woman’s daily recommended intake), there wasn’t really anything I could complain about. With a limited budget that needs to deliver on taste in large quantities, HDH seemed to be doing the best they could–or so I thought.

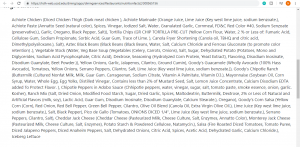

After perusing the HDH website for noodle nutrition facts, I decided to take a look at one of my favorite places–Goody’s. After all, how bad could a burrito bowl be? Well, much to my chagrin:

Let’s go through this deadly ingredient list by first talking about MSG (monosodium glutamate), something that you’re probably somewhat familiar with. If not, your body certainly is, as MSG and its derivatives are ubiquitous in nearly every dining hall. MSG is often immediately associated with Asian cuisine, but the reality is that only a small amount of MSG is actually present in Asian foods; foods like lunch meats, frozen entrees, prepackaged sauces, salad dressings, mayonnaise, potato chips, and other processed items contain much larger amounts of MSG, simply because it has the ability to stimulate the 5th taste–a rich, earthy umami flavoring that is reminiscent of beef and creates a creamy texture that can hit more tastebuds. This flavor is much more difficult and expensive to create organically, so MSG is really a win-win for food manufacturers, who can use it to make their food cheaper and more palatable (2).

Now I know what some of you are thinking, “MSG isn’t even in the chicken bowl!,” and a quick glance proves this to be true. However, MSG is one of the most covert ingredients in our food system today. Much like an undercover agent, MSG possesses the ability to take on various names such as “hydrolyzed vegetable protein” and “natural flavors.” It is no coincidence that these names have considerably more marketing appeal than “monosodium glutamate.” Why? Well, the food industry has a special knack for getting what they want from the Food and Drug Agency, and a product of this cozy relationship is the ability to name an additive in a variety of ways (2).

This became pretty evident when I decided to see what the effects of MSG were– beyond the occasional headache. Independent government studies show that,

in rats, a high dosage of MSG narrows blood flow in the arteries, which can lead to cardiac issues later in life. This same study shows that neonatal rats fed MSG develop weight abnormalities and learning disabilities later in life. Human studies report that it wasn’t just headaches linked to MSG, but also dizziness, diarrhea, chest tightness, burning, and asthma. Before I could fall any further down an MSG rabbit hole, however, I was stopped by an unfortunate lack of research, as scientists find it difficult to isolate MSG’s effects with so many labelling loopholes (2).

Instead, I stayed on the HDH website and found an incredible variety of harmful ingredients present across campus. Red color #40 is made from coal tars and petroleum distillates ( banned in France, England, Norway, and Finland). Food from Roots to the Bistro was being cooked in an oil mixture full of tBHQ–a controversial ingredient that has been linked to protecting and promoting cancer (4). All of a sudden, HDH’s “healthy” facade began to fall apart. Everytime I went to eat somewhere, I saw a sharp contrast between the bright TV screens showing smiling UCSD dietitians promoting “Making healthier choices” and the reality, which was that the only choice was the preservative-laden one, whether you were at the salad bar or the pizza station.

Foods that are chock-full of preservatives impact how epigenetic markers operate. For instance, highly processed and sugary western diets can alter gene expression and prevent the utility of the gut microbiome’s short chain fatty acid that helps us digest fiber. Highly processed compounds have the ability to alter the gut’s chromatin environment and transcription of genes, which means certain genes could incorrectly be turned “on” or “off,”, increasing one’s probability of contracting certain health ailments (3).

So what do we do? Stop eating? Sell our dining dollars altogether? Both? Well, for one, it is definitely important to be more cognizant of these factors that can impede upon your health. The preservatives in these foods wreak havoc on their nutrition value, making a milkshake at 64 degrees 1000 calories and nearly 100% of one’ daily fat intake. Even healthier choices might be blocked from achieving their superfood potential because of the presence of preservatives.

While this may seem fairly minor if you don’t suffer from any pre-existing health conditions, the compounding effect of eating such things day in and day out will affect one’s academic ability. One may gain weight or feel less energized, and consequently, they might lack the ability to produce their best academic work. In such an academically rigorous and stressful environment, it is imperative that we manage all our lifestyle factors to help us succeed.

Think about it this way: In order to run a fast race, an athlete would control his or her diet, condition, and sleep to optimize performance. By the same vein, we as students need to make a conscious effort to eat well, which can lead to constructive psychological effects. Not only do we have more energy, but we are also more likely to execute a chain of productive tasks because we feel more confident in our choices. Eating healthy creates momentum. If we are the type of person to eat well, we may also be the type of person to not procrastinate. If we don’t procrastinate then we may as well carry that momentum to become the type of person who works out regularly.

So no, there is no need to avoid MSG like the plague and become fearful of high fructose corn syrup and red #40. That can become obsessive and mentally restrictive. But what we should do is be aware of its prominence in dining hall food and seek to minimize our consumption of it as much as possible. The way to do this is by using our voice as students to demand higher-quality food. This doesn’t mean asking for Whole Foods to cater our meals, but it is certainly possible and practicable to ask that HDH focuses on making the food more nourishing and less mind-numbing.

Sources:

Ohashi, K, et al. “High Fructose Consumption Induces DNA Methylation at PPARα and CPT1A Promoter Regions in the Rat Liver.” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications., U.S. National Library of Medicine, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26519879.

Scopp, Alfred L. “MSG and Hydrolyzed Vegetable Protein Induced Headache: Review and Case Studies.” American Headache Society, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 20 May 2005, headachejournal.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1526-4610.1991.hed3102107.x.

Shintyapina, Alexandra B, et al. “The Gene Expression Profile of a Drug Metabolism System and Signal Transduction Pathways in the Liver of Mice Treated with Tert-Butylhydroquinone or 3-(3′-Tert-Butyl-4′-Hydroxyphenyl)Propylthiosulfonate of Sodium.” PloS One, Public Library of Science, 3 May 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5415222/.

Zhang, Yi, and Tatiana G. Kutateladze. “Diet and the Epigenome.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 28 Aug. 2018, www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-05778-1.