UTS Staff Writer | SQ Online (2014-15)

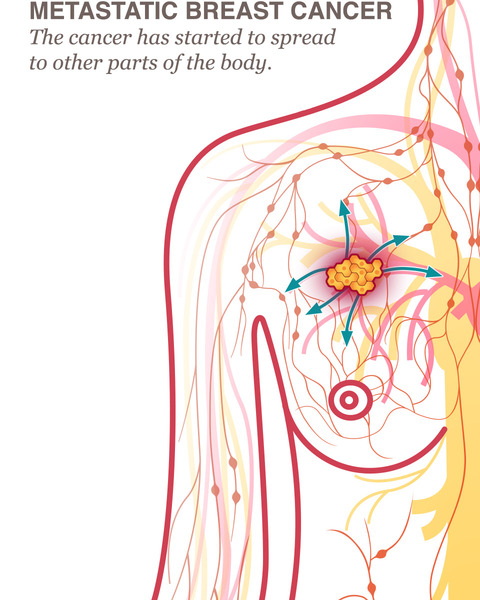

With an alarming number of 232,670 new cases reported in the United States in the past year, breast cancer continues to be one of the most rampant manifestations of cancers today. It is the second leading cause of death among women. Cutting-edge research has allowed scientists and physicians to develop a number of treatment methods and preventive measures to fight breast cancer. However, more often than not, breast cancer can metastasize, or spread, to different parts of the body through lymph and blood vessels. Once the primary breast tumor has metastasized, the cancer is even more difficult to treat, and patients are often devastatingly forced to accept that there is no cure. Metastasis continues to be a troubling issue among other cancers as well. Primary tumors can be removed surgically, but metastatic breast cancer can never be completely cured. With this in mind, researchers at UC San Diego have identified an enzyme that controls the metastasis of breast cancer. This research has immense implications, such as preventing primary breast cancer tumors from metastasizing, which ultimately could lead to successful and easy treatment plans along with higher overall survival rates.

Cancer Basics

In order for a normal human cell to become cancerous, it must undergo multiple gene mutations, such as in the genes that control the cell’s growth signals. Additionally, these cells attain unlimited replicative possibilities and have the ability to avoid apoptosis, a mechanism for cell self-destruction that is essential in normal human cells. These deadly cells are unstoppable if they grow enough to spread throughout the body.

The Problem of Breast Cancer Recurrence

Many women around the world affected by this disease experience recurrence, meaning that the cancer returns after the primary tumor has been removed from the breast. Recurrence can occur locally, in which the cancer forms close to or at the exact location as the previous tumor, or it can occur at a more distant location in the body, which is caused by the metastasis of the original primary tumor. As such, breast cancer, like most other cancers, remains a deadly disease that is challenging to control completely. Breast cancer cells tend to spread to the chest wall, lymph nodes, bones, lungs, liver, and brain. While chemotherapy and radiotherapy are currently treatment options for metastatic breast cancer, they are not completely effective and take a considerable physical and emotional toll on patients.

UCSD’s Contribution to the Breast Cancer Problem

Because the metastasis of primary breast cancer tumors is a recurring public health issue, many scientists have been researching the genetic variables that cause cancer cells to spread. In particular, one research lab at UCSD’s School of Medicine has focused on studying the metastasis of breast cancer cells. A study led by postdoctoral researcher, Dr. Xuefang Wu, PhD identified a protein called Ubc13 that is crucial for the metastatic spread of breast cancer cells. One notable point found in the study was that primary and metastatic breast cancer cells have elevated expression levels of Ubc13. What was surprising to the researchers was that the loss of the Ubc13 protein only prevented the growth of metastatic breast cancer cells, with no effect on primary tumor growth and development. This proved that this particular protein was unique in playing a role specifically in the metastasis of the breast cancer.

To confirm that their findings could be replicated in vivo (studies on live animals), Wu and his team studied the protein’s effect on mice. The Ubc13 protein regulates the p38 gene, which produces yet another protein that is essential in breast cancer metastasis. In this part of the study, Wu silenced the Ubc13 and p38 genes in human breast cancer cell lines before injecting them into mice. Their findings supported their previous studies – primary tumors formed, but metastasis did not occur.

Wu’s novel research on Ubc13 proves the complexity of the intricate roles that individual proteins play in our bodies. This study has vast clinical implications, including the use of p38 pharmacological inhibitors which can ultimately block the metastasis of breast cancer cells. Such inhibitors were successfully used in mice, therefore suggesting that they may also be used as anti-metastatic drugs in human breast cancer. As research on breast cancer and its deadly spread throughout the body continues, identifying Ubc13 as a protein that controls breast cancer metastasis may bring us one step closer to a victory against this deadly disease.

[hr gap=”0″]

Sources:

- “Metastatic Cancer.” National Cancer Institute. National Institutes of Health, 28 Mar. 2013. Web. <http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Sites-Types/metastatic>

- “Where Breast Cancer Might Come Back and How to Detect It.” Breastcancer.org. Breastcancer.org, 25 Mar. 2014. Web. <http://www.breastcancer.org/symptoms/types/recur_metast/where_recur>

- Xuefeng Wu, Weizhou Zhang, Joan Font-Burgada et al. “Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc13 controls breast cancer metastasis through a TAK1-p38 MAP kinase cascade.” PNAS 2014 111 (38) 13875; September 4, 2014, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414358111

- http://www.nationalbreastcancer.org/metastatic-breast-cancer

Image Sources:

- http://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http%3A%2F%2Fs3.amazonaws.com%2Fnbcf-production-assets%2Fattachments%2F000%2F000%2F332%2Fstandard%2F146fd9abf21fbbafd9bd4beceade132d&imgrefurl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.nationalbreastcancer.org%2Fmetastatic-breast-cancer&h=600&w=480&tbnid=5gyvT2pThHmmaM%3A&zoom=1&docid=uMAnYPD2PYFT1M&ei=Y8A5VPrsOdPkoASNyIDoAQ&tbm=isch&ved=0CDMQMygAMAA&iact=rc&uact=3&dur=600&page=1&start=0&ndsp=16

- https://health.ucsd.edu/news/releases/PublishingImages/mouse_ubc13_enzyme.jpg