Written by Anna Alvarado | UTS Staff Writer | SQ Online (2013-14)

The SIMPHONY study, which recently earned support from the Grammy Foundation, is unique because it peers into the impact of musical training on brain development.

The human body functions much like an orchestra, with the brain as the conductor. The brain controls every aspect of our body, from the metronome that is our heart to the fine flicks of our fingertips. It is no surprise, then, that great minds like Beethoven and Bach produced critically acclaimed works of music. There is a connection between the mind and music, with many studies displaying the role of music in brain perception and function. However, little is known about the impact of musical play on brain development. Most studies focus on the impact of music on the ability to think and learn but few actually elucidate the impact of learning music on brain growth.

Researchers from the Center of Human Development (CHD) here at UC San Diego are looking at this relationship between learning music and brain development over time. Investigator Dr. John Iversen aims to unravel this relationship through a 5-year longitudinal study named SIMPHONY (Studying the Impact Music Practice Has On Neurodevelopment in Youth). This study is a part of a larger study called PLING (Pediatric Longitudinal Imaging, Neurocognition, and Genetics), which investigates the impact of environmental factors on brain growth and its connection to behavior.

“Past studies have shown differences in adult musicians’ brains in comparison to others,” said Dr. Iversen, “but we’re not sure if these differences are due to music training, or if they were simply there to begin with, perhaps explaining why they became successful musicians in the first place.”

The study hopes to answer a “chicken or the egg” question: Are people naturally inclined to play music or is their musical training the reason for their strong aptitude in music?

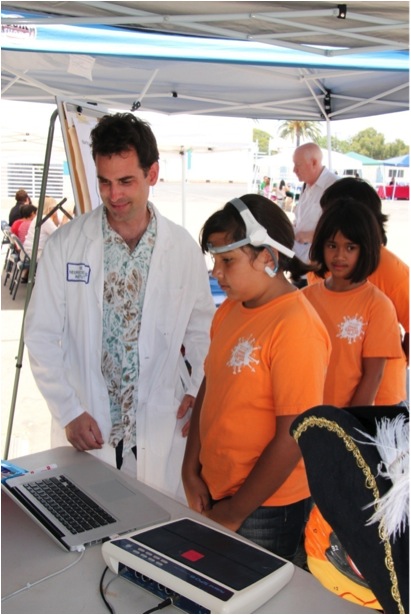

The study looks at a group of young children ages 5-8 years old who are participating in musical training and tracks their brain development through neurocomputational techniques over the span of 5 years. To ensure accurate quantification of the effects of musical training alone, various control groups were established.

“We have two types of control groups,” said Dr. Iversen, “One is [a] passive [control] where there is no musical training and the other is what we call an active control where we look at brain development in kids participating in activities [other than music], like karate. This is to see if it really is the music that is causing any changes.”

These controls are compared against children who are involved in musical training.

How exactly is brain development quantified? Iversen and his team use Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to measure changes in the kids’ brains as they progress through the program.

“We look at the area and thickness of different regions of the cortex,” Dr. Iversen states, “We also look to see if different areas of the brain are growing faster or slower than others.” Cortical thickness as well as the rate and number of neural connections made can indicate where and how musical training impacts the child’s brain growth.

Dr. Iversen and his colleagues just finished their first year of the study that provided some interesting results.

“We did find some strong connections between the development of brain structure and the ability of kids to move along to the beat of music, which provides a strong base for finding music effects,” said Iversen. “Next it will be interesting to see if kids who improve in their synchronization ability also show corresponding brain changes.”

The SIMPHONY study incorporates both learning and fun throughout their study. Children get a chance to hone their musical talents and ignite their interest in science as well.

“It is really great working with children,” said Dr. Iversen. “We hold yearly data camps where we collect data from the group of children but at the same time teach kids about the brain and expose them to science and the UCSD campus. It’s really fun.”

The study continues to find new information, further revealing the harmonious relationship between music and the mind.

“The next step is to collect and analyze the second year of data,” said Dr. Iversen. “We may have found a connection between rhythmic skill and various brain areas.” The findings from SIMPHONY will further reinforce the importance of multidisciplinary learning and the importance of musical education for youth across the country.