Have you woken up, thinking you were falling only to realize you’ve been in bed this whole time? Maybe you imagined yourself falling off a cliff or tripping on an empty soda can on the floor. Whatever the scene, you may have woken up panting, and come to an immediate conclusion that you’re going insane. Here’s the good news–you’re not.

These experiences are called hypnic jerks, random and involuntary muscle spasms that occur as people fall asleep. Interestingly, a total of 60 to 70 percent of the population has experienced these jerking movements at least once in their sleep. Typically these spasms are subtle, but some of these “falling” sensations and spasms may be more obvious than others. In that case, you’d jolt awake. This experience most often occurs when transitioning into sleep. The jerks are natural occurrences and don’t primarily indicate significant medical conditions, as the information in this article applies to common hypnic jerks. However, some can be indicative of epileptic seizures or tremors noticed in diseases such as epilepsy or Parkinson’s Disease. Despite their prevalence, we have yet to find concrete explanations on why hypnic jerks occur. Nevertheless, there are strong scientific theories on why people may commonly experience these spasms.

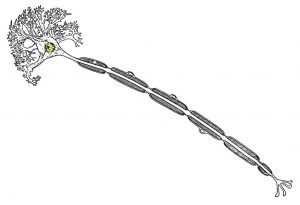

The first hypothesis refers to sleep atonia, the natural paralysis of our body while we are asleep. (Note, we are not addressing sleep paralysis where individuals remain awake in bed but cannot move their bodies.) Motor neurons function as they are triggered by electrical signals sent from the brain. However, the same electrical signals can’t trigger the motor neurons to move as usual during sleep. The threshold of electrical activity required to stimulate the motor neurons is increased, and thus signals that would normally activate movement, such as in one’s limbs, would be insufficient to induce movement. This natural change in the electrical activity occurs to inhibit large and active movements while we’re asleep. Could you imagine your body remaining active in the midst of your action-filled Avengers dream? It would literally be a physical nightmare.

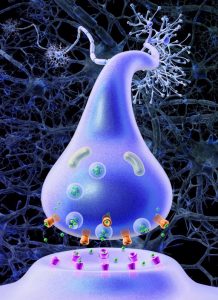

Higher thresholds of electrical activity for motor neurons don’t simply “turn on” when we enter sleep. Instead, there are two neural subsystems controlling our bodies: one managing sleep, and one managing wakefulness. The first sleep system, the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO), is a group of sleep-inducing neurons located close to the optic chiasm, the precise crossing point of the optic nerves. The VLPO contains neurotransmitters called gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) which restrain neurotransmitters, like serotonin or histamine, that are actively released in the wakeful state. The VLPO activity is affected by the indirect influences of the suprachiasmatic nucleus according to the circadian rhythm of each individual. When the VLPO is activated, the individual drifts into sleep and the necessary threshold of electrical activity increases. There are also suggestions that the VLPO is intentionally placed near the optic nerves to receive light sensory information when day or night time arrives to regulate sleep.

The second wakefulness system is the reticular activating system (RAS), a group of neurons influencing behavior and consciousness. The RAS is mostly stimulated at the presence of orexin, a wakefulness inducing peptide that is produced when the optic nerves detect daytime light. As the VLPO takes full control when someone is on the verge of falling asleep, the overlap of control between these two neural systems produces these muscle spasms before the muscles finally relax and enter temporary paralysis.

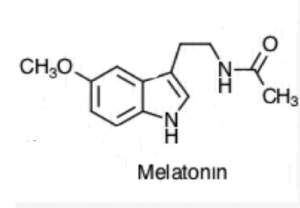

The second hypothesis refers to the concept of falling. Before diving into the hypothesis, it is necessary to learn about a sleep-specific hormone produced in the pineal gland of the endocrine system. The hormone is called melatonin, and it helps regulate sleep and the circadian rhythm. This sleep regulating hormone is released in the presence of darkness, and that’s why many sleep specialists recommend people to sleep in complete darkness without light seeping through. The melatonin release signals the body about the coming nighttime in accordance with the circadian rhythm. A calm wakefulness is induced as the body temperature decreases, the heart rate slows down, and the body slowly relaxes its muscles.

How does muscle relaxation relate to a “falling sensation”? Usually, the relaxation of muscles occurs in a progressive manner, but a faster muscle relaxation when entering sleep can cause one to feel like they’re “falling” in real life. The brain misunderstands the faster muscle relaxation as a warning before hitting the ground and ultimately initiates a hypnic jerk. However, we don’t constantly jerk awake from dreams that consist of us falling, because by the time you enter the deep rapid eye movement (REM) stage of sleep (where dreams occur), your muscles are at the height of sleep atonia, or temporary paralysis. As a result, these hypnic jerks don’t primarily interfere with dreams during REM sleep, but are more commonly experienced when transitioning into sleep.

Certain lifestyles or conditions that individuals face can increase the likelihood that they will experience hypnic jerks. Some of these factors include exercising at night, consuming excessive amounts of caffeine, experiencing overwhelming stress or anxiety, keeping irregular sleeping schedules, and more. These factors can serve as active stimulants that prevent the wakefulness-inducing neurons from being sufficiently subdued in sleep, thus the continued stimulation during sleep can be expressed through hypnic jerks. For example, as a result of the current pandemic, Zoom calls are integrated into our daily lives. In return, our screen time exponentially increases and these virtual interactions paired with quarantine bring waves of burnouts and skyrocketing stress levels. Such unhealthy stimulators can take obvious tolls on sleep quality and induce more frequent hypnic jerks.

Unfortunately, we cannot entirely stop hypnic jerks from occurring as they are natural processes, yet most hypnic jerks are bearable and often negligible. Minor hypnic jerks are common and do not serve as indicators of prolonged chronic illnesses. In the case of observing extreme jerks, however, consulting with your doctor for professional advice is advisable.

Reflecting on my sleep journey, I remember distant memories of jolting awake from my sleep after especially exhausting days. Immediately returning to conscious awareness, I would notice my heart thumping and take a long, silent moment contemplating my health in a confused state. Looking back, there was no reason to be afraid or disturbed. These strange involuntary muscle spasms are experienced by over half the human population. To put it into perspective, about the same percentage of our population has brown eyes. So, if you ever find yourself jolting awake in the near future, don’t stress–it’s just a common hypnic jerk that hundreds if not thousands and millions of others will experience that same night.

Sources:

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/324666#frequency

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/myoclonus/symptoms-causes/syc-20350459

- https://www.webmd.com/sleep-disorders/sleep-101

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12401341/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/ventrolateral-preoptic-nucleus

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12405980/

- https://www.statpearls.com/ArticleLibrary/viewarticle/28435

- https://elemental.medium.com/why-your-body-sometimes-jerks-while-you-drift-into-sleep-88f8d28d643a

- https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/melatonin-what-you-need-to-know

- https://www.sleepfoundation.org/bedroom-environment/making-your-room-dark

- https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/melatonin-and-sleep#what-it-is

- https://doi.org/10.3828/bfarm.2006.4.11

- https://www.sleep.org/hypnic-jerks/

- https://www.healthline.com/health/eye-health/eye-color-percentages#percentages

Images:

- https://unsplash.com/photos/bxt-tWSF-Ko

- https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/1a4a15a8-faa3-4b2b-8fb2-6024e8ed2d0b

- https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/5019bae0-a7ec-4c69-8066-459301d81075

- https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/28b8e2c4-ca41-41f1-8f14-610224201da5

- https://unsplash.com/photos/8PZ64Ca8AoY