Using mouse models to understand causes and develop treatments for polycystic ovary syndrome

Unusual hair growth, cystic acne flare-ups, weight gain, and irregular periods are all uncomfortable hallmarks of adolescence. However, for some individuals, these experiences are more extreme and continue past the expected awkward teenage years. Such was the case for a UC San Diego student, Rachel, whose name has been changed to protect her privacy. Upon visiting her OB-GYN, Rachel was told that many individuals combat menstrual irregularities and that she needed to be placed on birth control pills (BCPs). While on the pill, Rachel continued to experience extreme fluctuations in weight gain and acne breakouts and noticed coarse hair popping up in places like her chin. However, despite the alterations in her body, Rachel’s circumstance was chalked up to a coming-of-age experience and there was never any further investigation into the probable cause of these symptoms.

Within only three months of going on BCPs, Rachel had gained over 100 pounds, had chronic acne, noticed a significant increase in facial hair, and her menstrual cycle had stopped despite her not being

pregnant. She soon realized that the sheer magnitude and persistence of her symptoms went beyond normal adolescent changes. Seeking professional help once again, she visited her general practitioner, who insisted that she was simply overeating due to anxiety, despite her having not significantly changed her eating habits. She saw two new OB-GYNs, who both regurgitated the same theory. Frustrated, she decided to make one last appointment with another doctor hoping they would understand the gravity of her symptoms rather than dismiss her. After explaining her story one last time, Rachel experienced a breakthrough with her doctor, who diagnosed her with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). The doctor explained that PCOS is often misdiagnosed due to symptom ambiguity and a lack of public awareness, but they agreed to work with her to create a treatment plan to alleviate her symptoms. Finally, Rachel was able to begin learning about her body and demystifying the symptoms of PCOS.

DEMYSTIFYING PCOS

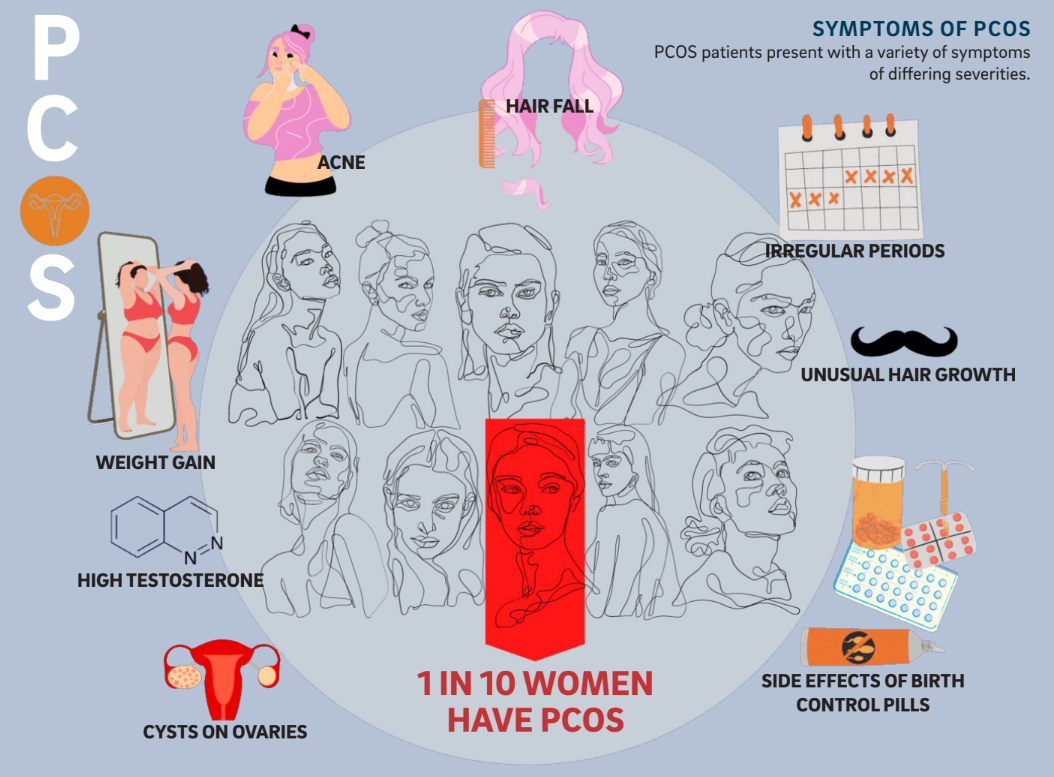

When PCOS was first described in 1935 by American gynecologists Irving Stein and Michael Leventhal it was considered a rare disorder. Today the US Office on Women’s Health reports that PCOS manifests, with differing symptoms and severity, in as many as 1 out of 10 people with uteri. PCOS is also a leading cause of infertility and is linked to an elevated likelihood of pregnancy complications including miscarriage, according to the CDC.

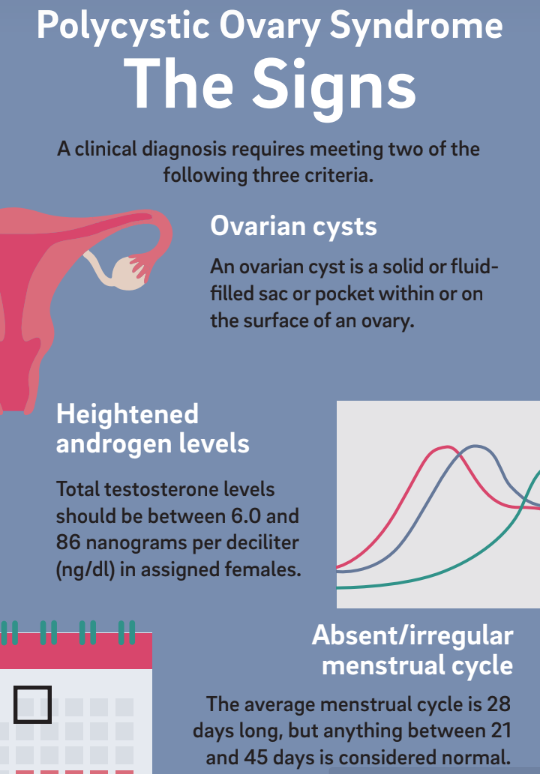

Unfortunately, many physicians do not perform the necessary diagnostic tests or recognize that PCOS has broad and potentially devastating consequences. Part of the issue can be attributed to the varied ways PCOS manifests. A clinical diagnosis of PCOS requires meeting two out of three criteria: ovaries with cysts, heightened levels of androgens such as testosterone, and absence or irregularity of the menstrual cycle. The other complicating factor is a lack of public awareness. According to the non-profit support organization PCOS Challenge, PCOS awareness and support organizations receive less than 0.1 percent of the government, corporate, foundation, and community funding that other health conditions receive.

Researchers are still unsure of the cause of PCOS; however, two notable labs at UC San Diego are currently using mouse models to push the frontier of PCOS research. The unusual characteristics of

mice have allowed one lab to study the relationship between PCOS and the gut microbiome.

A KICK IN THE GUT

In the Thackray laboratory at the UC San Diego School of Medicine undergraduate researcher, Reeya Shah studied whether exposure to a healthy gut microbiome is protective against the development of PCOS symptoms. The gut microbiome is vast and complex, with around 100 trillion bacteria making their home in the average human intestinal tract. It is believed that the occurrence and development of a variety of endocrine and metabolic diseases, like PCOS, are affected by the dynamics of intestinal bacteria.

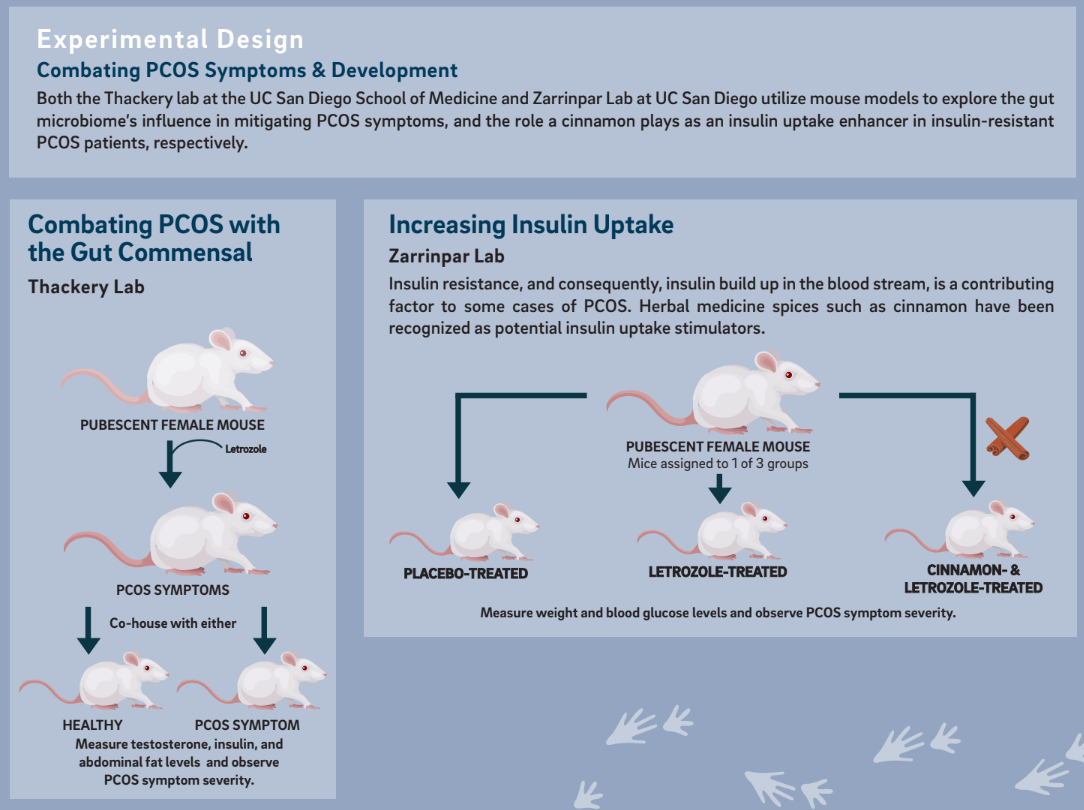

The researchers used mouse models for the study. Models are often used in labs because obtaining permission for using humans to test scientific hypotheses is very difficult and often dangerous. Mice were an efficient model system for this study because they consume each other’s feces for nutrients, which means gut microbes can be readily transferred.

To induce PCOS symptoms, the researchers treated mouse models with letrozole, a drug that inhibits the conversion of testosterone to estrogen, thereby increasing testosterone levels in the bloodstream. Letrozole treatment of pubescent female mice resulted in the development of hallmark symptoms of PCOS, including hyperandrogenism and polycystic ovaries. These letrozole-treated mice also exhibited metabolic dysregulation similar to humans with PCOS, including weight gain, insulin resistance, and elevated fasting blood glucose and insulin levels. The researchers then designed a housing space for the mice such that a letrozole-treated PCOS mouse was paired either with a healthy mouse or another letrozole-treated mouse.

The researchers concluded that letrozole-treated mice that were co-housed with healthy placebo mice had testosterone, insulin, and abdominal fat levels similar to those healthy mice. The mice also had similar patterns of weight gain, which indicated a healthier pattern in insulin uptake that resulted in less fat storage in the body. Neither the letrozole-treated mice paired together nor the healthy mice paired together underwent any significant changes from their initial states.

The researchers concluded that letrozole-treated mice that were co-housed with healthy placebo mice had testosterone, insulin, and abdominal fat levels similar to those healthy mice. The mice also had similar patterns of weight gain, which indicated a healthier pattern in insulin uptake that resulted in less fat storage in the body. Neither the letrozole-treated mice paired together nor the healthy mice paired together underwent any significant changes from their initial states.

Overall, co-housing letrozole-treated mice with healthy mice resulted in the improvement of PCOS symptoms compared with co-housing them with other letrozole-treated mice. These results implied that an altered gut microbiome has a possible causal link to PCOS symptoms. However, applications of this particular treatment to humans are still far on the horizon. Other labs have taken advantage of similar mouse models to study the effects of metabolic factors.

SPICING IT UP

Undergraduate researcher Shiantel Chiang in the Zarrinpar laboratory at UC San Diego focused on the link between insulin uptake and PCOS. Although it is often perceived as a reproductive disorder, PCOS is also a general metabolic disorder, where abnormalities in the body disrupt metabolism. For instance, a contributing factor to some cases of PCOS is the difficulty for the body to recognize the hormone insulin, which tells the body to store sugars in cells. This condition, called insulin resistance, causes insulin and sugar to build up in the bloodstream. High insulin levels can increase the production of androgens. Elevated androgen levels are associated with increased body hair growth, acne, irregular periods, and unusually distributed weight gain that some PCOS patients, like Rachel, experience.

Undergraduate researcher Shiantel Chiang in the Zarrinpar laboratory at UC San Diego focused on the link between insulin uptake and PCOS. Although it is often perceived as a reproductive disorder, PCOS is also a general metabolic disorder, where abnormalities in the body disrupt metabolism. For instance, a contributing factor to some cases of PCOS is the difficulty for the body to recognize the hormone insulin, which tells the body to store sugars in cells. This condition, called insulin resistance, causes insulin and sugar to build up in the bloodstream. High insulin levels can increase the production of androgens. Elevated androgen levels are associated with increased body hair growth, acne, irregular periods, and unusually distributed weight gain that some PCOS patients, like Rachel, experience.

Chiang was interested in methods to regulate PCOS symptoms by improving the uptake of insulin. Inspired by her previous experience with herbal medicine, Chiang looked into herbal treatments for insulin resistance. The researchers chose to focus on a commonly used spice that has a long history in medicine –cinnamon.

According to a 2010 study reported in the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, cinnamon mitigates insulin resistance caused by high fructose diets by enhancing the insulin signaling pathway. The researchers thus decided to study the effect and mechanism of cinnamon on PCOS using the letrozole mouse model.

According to a 2010 study reported in the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, cinnamon mitigates insulin resistance caused by high fructose diets by enhancing the insulin signaling pathway. The researchers thus decided to study the effect and mechanism of cinnamon on PCOS using the letrozole mouse model.

To test this hypothesis, the Zarrinpar lab designed a study with female prepubescent mice. These mice were randomly divided into three groups: a control group, a letrozole-treated group, and a letrozole-

treated and cinnamon-treated mice group. The control group received a treatment of daily placebo supplement, which was not expected to have any metabolic impact. The letrozole and cinnamon-treated mice group received letrozole treatment along with a cinnamon powder supplement. The mice were weighed every two days, and their glucose levels were measured by blood sampling using a blood glucose meter for 20 days.

The researchers found that the letrozole-treated and cinnamon-treated mice groups showed improved symptoms of PCOS as compared to the mice treated solely with letrozole. The bodyweight of the mice

in this group had declined, possibly indicating a healthier insulin signaling pathway. The blood glucose levels also showed a reduction in excess blood glucose, whereas the control group and letrozole-treated

mice group showed no changes from their initial states.

Reduction in body weight and excessive blood glucose helps reduce PCOS symptoms and depicts cinnamon as a possible alternative method of symptom management. Rachel’s negative experience with

BCPs is not unusual; many patients experience side effects or a lack of symptom relief. Zarrinpar labs’ research could help such patients with managing their PCOS.

STRIVING FOR MORE EQUITABLE RESEARCH

Through the use of mouse models, student researchers at UC San Diego have uncovered that the gut microbiome may play a role in PCOS in some patients, as well as the possibility that cinnamon extract might improve outcomes for those with PCOS. Research labs like the Thackray and Zarrinpar labs embody the scientific push to new frontiers and do especially important work by focusing on underrepresented patients and syndromes.

Through the use of mouse models, student researchers at UC San Diego have uncovered that the gut microbiome may play a role in PCOS in some patients, as well as the possibility that cinnamon extract might improve outcomes for those with PCOS. Research labs like the Thackray and Zarrinpar labs embody the scientific push to new frontiers and do especially important work by focusing on underrepresented patients and syndromes.

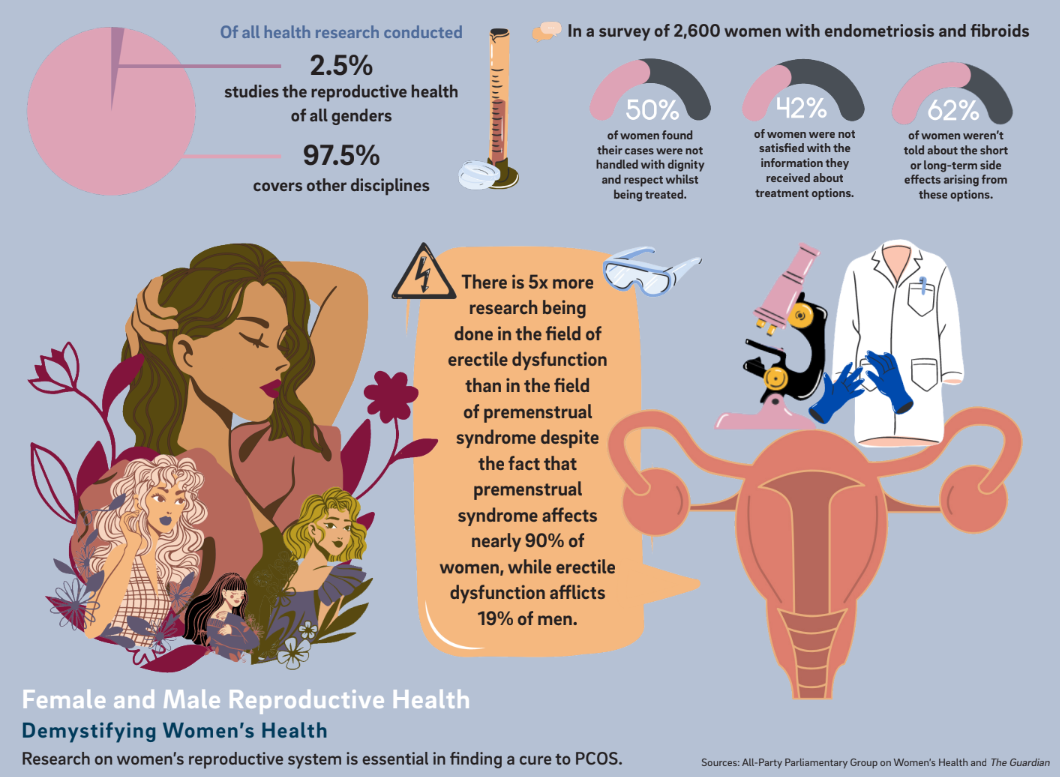

According to The Guardian, less than 2.5% of publicly funded research has been dedicated exclusively to uterine health even though 1 out of 3 people with uteri will experience severe reproductive health issues in their lifetime. The issue stems not from any one individual acting in bad faith, but rather from a medical framework that has historically overlooked uterine health. In an interview with the New York Times, Dr. Janine Austin Clayton, director of the Office of Women’s Health, noted that male medical specimens and trial subjects have historically outnumbered females, and the inequity of information has led to dangerous outcomes in the field. For example, heart attacks are 50% more likely to be misdiagnosed in British women than men, according to a study by Leeds University.

Medicine is a practice built on the foundation of rigorous studies, but the unequal historical focus results in modern medicine failing to serve the breadth of its patients. Increased research into PCOS from labs like the Thackray Lab and the Zarrinpar Lab represents one bright spot for the future of equitable and inclusive medicine.

Written by Vidisha Marwaha & Meline Norquist

Vidisha is a second year student majoring in Human Biology. Meline is a second year student majoring in General Biology.