“Oregon is legalizing mushrooms. Ketamine can be delivered to your home. People are microdosing LSD to treat pandemic-related anxiety, and Wall Street is pouring billions into companies that sell mind-altering drugs.” These were the opening remarks of a recent New York Times article by Kat Eschner, a Toronto-based science and business journalist, who goes on to report rising levels of global interest in psychedelics as well as their potential utility in treating a wide-range of mental-health disorders like depression and addiction. That’s right: psychedelics, long-time residents of America’s cultural and medical outskirts, are steadily making their move into the clinical and scientific mainstream, reforming their tarnished image as they seek to usher in a new, hopeful, and revolutionary era in the ongoing, strenuous battle against mental illness.

Ask anyone what they know about the history of psychedelic drugs and their mind will probably race back to the sixties. Their answer, likely to resemble the plot of a classic comedy, might involve hippies, anti-war fervor, rebellious teens, and that crazy Harvard professor who gave students LSD as part of a sequence of highly flawed and mismanaged studies. But psychedelics were around long before Tim Leary (the aforementioned Harvard professor) encouraged listeners to “turn on, tune in, drop out,” a phrase he reportedly thought up while showering. A prominent spiritual and religious motif across many ancient cultures, psychedelic use dates back thousands of years. From the Aztecs who regularly consumed ‘shrooms, to ancient Greek villagers who drank psychoactive concoctions, to the many psychedelic-obsessed folks in ancient India–where deep admiration for psychedelics even influenced the writing of religious hymns–the use and significance of psychedelic substances have spanned the globe, influencing people and cultures of all sorts.

Tethered to such historical and cultural significance, psychedelics are a natural subject of scientific wonder, fueling questions that range from the surprisingly complicated what to the even more complex how. Let’s begin with the former: what are psychedelics?

Type “psychedelics” into your search bar, and the word “psychoactive” is likely to dominate your screen’s real estate. The only problem: “psychoactive” doesn’t do much to actually describe what psychedelics are, frustratingly complicating an already confusing topic. However, the strange and difficult truth is that there isn’t an alternative; when learning about psychedelics, investigating what they are and what they do, we’re forced to embrace the complexity. That’s exactly what psychiatrist Daniel X. Freedman did, vividly describing the seemingly indescribable experiences that psychedelics can foster.

In his 1968 article about LSD, Freedman argued that the psychedelic helps activate a normally inactive mental quality we all have–“‘portentousness’–the capacity of the mind to see more than it can tell, to experience more than it can explicate, to believe in and be impressed with more than it can rationally justify, to experience boundlessness and ‘boundaryless’ events, from the banal to the profound.”

As Freedman articulates, psychedelics connect us to sensations and phenomena we seldom, if at all, come across, bridging the gap between our everyday experiences and those we never imagined possible. Thus, when tasked with the tricky job of describing what psychedelics are, it may be helpful to take a page from Dr. Freedman and move past the term “psychoactive” to capture how psychedelics unleash some of the most powerful and mysterious neural qualities at our disposal.

Now, how do psychedelics work?

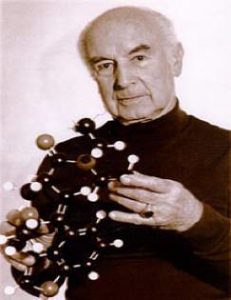

In 1943, Albert Hoffman unknowingly tripped on the very compound he created only five years earlier in 1938: lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). So overwhelmed by the drug, Hoffman hurried home from his lab and later detailed an illustrative account of the compound’s powerful mental effects, reporting feelings of unusual dizziness and a sense of heightened imagination. About a decade later, researchers achieved another milestone when discovering that LSD and serotonin–a neurological chemical that promotes happiness–had very similar chemical structures. A revelatory link between LSD and serotonin, the discovery prompted biochemists D.W Woodley and E. Shaw to form a critical hypothesis concerning LSD function in the brain: “the mental disturbances caused by lysergic acid diethylamide were to be attributed to an interference with the action of serotonin in the brain.” Amazingly, their almost seven-decade-old claim aligns almost perfectly with the now prevailing belief that psychedelics work by serving as agonists to 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptors.

Great! But again we ask, what does that mean?

Let’s first break down “5-hydroxytryptamine 2A” into its constituents. 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) is the fancy scientific name for serotonin, and 2A is simply an identifier that denotes a specific type of serotonin receptor (like flavors of ice cream, there are multiple kinds of serotonin receptors). Now, what’s an agonist? An agonist describes a chemical that attaches to and activates receptors. Put all of this together and you get a much simpler, jargon-free overview of psychedelic function: in the brain, psychedelic compounds latch onto and activate certain receptors that usually interact with serotonin, a process that scientists are confident plays a large role in psychedelic effects.

Still, scientists don’t know everything that goes on when the brain encounters a psychedelic. Though certainly an illuminating discovery, the interaction between psychedelics and serotonin receptors is but one process among a sea of puzzling processes that assemble the incredibly profound and sometimes “life-changing” psychedelic experiences that have captivated so many for so long. Only with more time and research can scientists fully unravel the elusive blueprints which underpin the massive yet subtle operation psychedelics conduct whilst in the brain.

Nevertheless, what we definitely do know is that psychedelics are powerful drugs. So powerful, in fact, that they may just be the long-awaited foot that finally kicks depression all the way to the curb.

One psychedelic in particular has sparked high and sustained interest across the healthcare industry: psilocybin. Present in mushrooms within the Psilocybe cubensis species, psilocybin is the chemical responsible for creating a user’s “trip.” Once consumed, psilocybin is converted into a chemical called psilocin, a process crucial to unleashing the ‘shroom’s observed effects. An almost perfect structural replica of serotonin, psilocin binds to and activates serotonin receptors in the brain, which, as mentioned earlier, triggers an intricate set of obscure processes.

Still, recent clinical research into psilocybin has profoundly expanded what we know about the compound, shining a light on the psychedelic’s stunning array of hopeful qualities and potentially groundbreaking clinical applications.

In a recent study, researchers analyzed psilocybin’s efficacy against Major Depressive Disorder, known informally as depression. In the experiment, twenty-seven depressed subjects were randomly split into two groups: an immediate treatment group and a delayed treatment group. Patients in the former group underwent the devised treatment plan at the beginning of the experiment while those in the latter group received treatment only eight weeks after the experiment’s start. Before treatment was administered, researchers recorded depression levels across both groups using an evaluation tool known as the GRID-Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (GRID-HAMD), which conveys both the frequency and intensity of a patient’s depression via a single score, to establish starting data. After treatment, new scores were logged and compared to these initial values.

The treatment took place over an eight-week period, beginning with a series of “preparatory meetings” that lasted about three weeks. Around week three, participants received their first dose of psilocybin, set at 20 mg, an amount described by the study as “moderately high.” A week later, a second 30 mg dose was administered. Supervised and cared for by members of the study’s staff, all patients were given support and assurance while under the drug’s influence. To assess the impact of psilocybin on the patients’ depression, GRID-HAMD scores were assessed and recorded one and four weeks after session two, marking the end of the treatment.

Upon comparing GRID-HAMD scores across the immediate treatment group to those collected from the delayed treatment group (whose members didn’t yet receive psilocybin) a promising observation quickly followed: the average GRID-HAMD scores obtained from the immediate treatment group were at least twelve points lower than those across the delayed treatment group, a powerful demonstration of the drug’s potent influence in curbing feelings of depression.

What’s more, once patients in the delayed treatment group received psilocybin, post-treatment GRID-HAMD scores across both of the study’s groups were compared to their corresponding baseline values, providing visibility into the drug’s overall effect on the patients’ depression. Researchers discovered that seventy-one percent of all of the subjects’ GRID-HAMD scores decreased at least fifty percent at both the first and fourth week after their last administered dose of psilocybin, a finding described in the study as a “clinically significant response.” Furthermore, more than half of the patients “met the criteria for remission of depression,” as their post-treatment GRID-HAMD scores did not exceed seven.

As American lawmakers and politicians tightened their opposition to psychedelics, responding frantically to the ever-expanding counterculture movement, our scientists were forced to ignore what these substances could accomplish and the lives they could improve. But now, old attitudes are changing. Psychedelic-based clinical research is on the rise, fueling sweeping shifts in the ways we perceive and talk about psychedelic treatments.

These shifts couldn’t come at a better time. Pain, uncertainty, and loss rage on, crippling our already fading sense of normalcy and hope. Now more than ever, exploring new avenues to improve mental health care is crucial as we prepare to navigate a tense and difficult future. Thus, if psychedelics do in fact rise to become our most powerful weapons against mental illness, why not embrace them with open arms?

References:

- https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/05/well/psychedelic-drugs-mental-health-therapy.html?searchResultPosition=1

- https://twitter.com/KatEschner?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Eauthor

- http://pitjournal.unc.edu/content/lsd-and-hippies-focused-analysis-criminalization-and-persecution-sixties

- https://alumni.berkeley.edu/california-magazine/spring-2015-dropouts-and-drop-ins/myth-dropout-turn-tune-drop-out-never-really

- https://www.nytimes.com/1996/06/01/us/timothy-leary-pied-piper-of-psychedelic-60-s-dies-at-75.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4813425/

- https://honorsandawards.iu.edu/awards/honoree/121.html

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/489589

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02791072.1979.10472092

- https://www.simplypsychology.org/what-is-serotonin.html

- https://www.pnas.org/content/40/4/228

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/serotonin-receptor

- https://www.osmosis.org/learn/Pharmacodynamics:_Agonist,_partial_agonist_and_antagonist

- https://www.med.unc.edu/pharm/a-scientific-first-how-psychedelics-bind-to-key-brain-cell-receptor/

- https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(20)31066-7?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0092867420310667%3Fshowall%3Dtrue#secsectitle0065

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=81-v8ePXPd4&t=62s

- https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/09/health/psychedelics-mdma-psilocybin-molly-mental-health.html?searchResultPosition=2

- http://bioweb.uwlax.edu/bio203/2011/bielmeie_luke/Pharmacology.htm

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7643046/

- https://iscdd.org/Resources.aspx#:~:text=GRID%2DHAMD-,The%20GRID%20Hamilton%20Rating%20Scale%20for%20Depression%20(GRID%2DHAMD),by%20Max%20Hamilton%20in%201960.&text=The%20GRID%2DHAMD%20was%20designed,relevant%20item%20in%20the%20scale