I have a confession to make: sometimes when I’m really, really bored, I find myself watching Riverdale. Anyone else? (Feel free to say no–I know you’re lying, and this is me calling you out on it). If you’ve ever watched the show–which, as we’ve established, I’m willing to bet you have–then you’ve been introduced to Betty Cooper, the goody-two-shoes with a dark side. (Note: by dark side, I’m referring to the fact that she’s a bit of a psychopath. Not the Blair Waldorf kind, but the Joe Goldberg kind). As much as I despise her character, she’s taught me a lot. The first thing would be to avoid crossing her, because the consequences are fatal (see: the dead body in her kitchen). The second would be that there’s a “serial killer gene” out there which, surprising nobody, she has.

To be honest, I’m not completely sure why it’s called the “serial killer gene.” If I had to guess why, I’d imagine it’s because it’s got more of a ring to it than “aggression proclivity gene.” In reality, it’s not a gene that creates serial killers, because that would be disconcerting, but rather a gene that’s linked to a predisposition for violence and aggression–which, to be fair, is still fairly alarming. The issue here isn’t that the gene has a catchy, soundbyte-friendly name; it’s that its misused as both a legal defense for murder, and as a prosecutorial “gotcha!” used to justify convictions in the absence of more concrete evidence. 2010 was the first year we saw the gene used successfully in order to defend a killer in Italy–Abdemalek Bayout–who admitted to stabbing a man to death. His attorneys simply argued that Bayout was mentally ill and not fully to blame for his actions, so the judge reduced his sentence from life in prison to a mere nine years. A later appeal proposed by Bayout’s attorneys in an effort to reduce his sentence saw Pietro Pietrini, a molecular neuroscientist at the University of Pisa, and Giuseppe Sartori, a cognitive neuroscientist at The University of Padova, discover that Bayout’s genetic makeup was to blame for why he committed the murder. The judge, once again, ruled in favor of Bayout, decreasing his sentence by another year. Here in the United States, notorious serial killers Bradley Waldroup and Brian Dugan were found to have the same exact gene that granted Bayout a commuted sentence. Fortunately for us, and unfortunately for them, their defense backfired. Waldroup was handed a life sentence; Dugan, ever the unlucky murderer, was sentenced to death shortly before the death penalty was banned. Even though all three killers had genetic makeups that would theoretically make them more inclined to aggression, they were hit with dramatically different sentences. It feels a bit incongruous, no matter what your take on the use of dubious genetic science in criminal court is. The whole concept of your genes being responsible for murder is not only a relatively new topic of research, but also a bit far-fetched. As we come to learn more about its role in creating killers–especially serial killers–we’re also learning more about the influence of the environment on psychological development.

The history of the genetic murderer isn’t a long one, but nowadays, genetics seem to explain a lot of mysterious things, so scientists took it upon themselves to see if it could explain the behavior of the most prolific serial killers. Initially, the most concrete evidence they could find revolved around sex chromosomes. In 1965, a survey performed on male prison inmates revealed that the majority of the inmates had an additional sex chromosome, leading geneticists to believe that an extra sex chromosome might correspond to a predisposition towards crime.

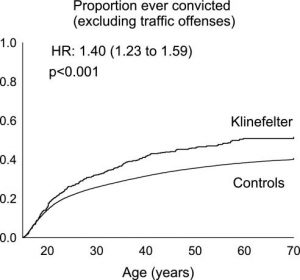

Another study compared subjects with XXY (otherwise known as Klinefelter’s Syndrome (KS)) and XYY genotypes to a counterpart subject with a normal sex genotype like XY or XX. 385 out of the 934 (~ 41.22%) subjects with KS were convicted at least once, compared to 37,085 out of 88,829 (~ 41.75%) of the control counterparts. Although the size of the pools vastly differed, the percentage of subjects who were convicted in both groups were almost exactly the same.

Image: The graph above compares subjects with KS to their controls clearly showing that as both categories of subjects aged, the proportion of subjects with KS who were convicted was higher than the proportion of control subjects who’ve been convicted (Source).

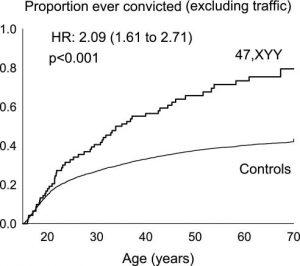

For subjects with the XYY sex chromosomes, roughly 50% of the subjects had committed at least one crime, while around 40.92% of their control counterparts had. Although there was a greater difference in this case, there wasn’t enough scientific evidence to back up the claim that sex chromosomes play a role in one’s propensity for aggression because the difference in subject pool sizes was so big. Therefore, scientists deemed the connection between crime and sex chromosomes as weak and definitely not enough evidence to draw any concrete conclusions to mitigate a crime.

Image: This graph compares those with an additional Y chromosome to their counterpart control subjects. Once again, as these subjects aged, the proportion of subjects with an additional Y chromosome who were convicted was higher than the proportion of control subjects who’ve been convicted. It’s important to note that the proportions have a greater difference in this graph than the previous graph (Source).

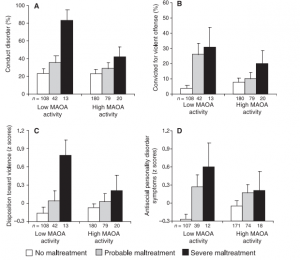

It stands to reason that there are very obvious environmental factors that can play a role in creating a serial killer, but scientists were eager to find a concrete genetic basis for criminality. They found it in Monoamine Oxidase A (MAOA), which has been credited with being the “most common denominator” amongst serial killers. MAOA is an enzyme that breaks down the neurotransmitters of crucial chemical compounds like serotonin and dopamine–compounds our brains produce that are typically associated with happiness– to allow for proper functioning during the synaptic transmission in the nervous system. Essentially, it keeps us happy, normal, and sane–a tall order for a single gene, huh?

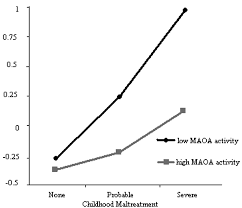

The issue occurs when there’s a low expression of it–MAOA-L. When that occurs , our bodies have higher levels of these chemical compounds, giving rise to aggressive behavior. Now, you might be asking yourselves: “how could higher levels of compounds associated with happiness create psychopaths?” The truth is, there’s an optimal amount that our bodies are used to and when those amounts change, the consequences are dire. In this case, the dysregulated levels of compounds such as serotonin negatively affect the way our brains react to social stimuli. The cause of MAOA-L is both a result of natural influences and environmental ones. Exposure to childhood trauma like abuse, loss, or bullying can contribute to the decreased expression of MAOA. This decrease in gene expression creates issues ranging from the benign like social awkwardness–to the deadly–like aggression and a proclivity for violence. Every now and then, these issues fester, creating a serial killer. It’s fair to say that, to an extent, we’re all slaves to our genetic makeup–and sometimes, the way the cards fall can save or take a life.

Image: The graphs compare people with low MAOA activity to people with high MAOA activity and take into account maltreatment as a child with white showing no maltreatment, gray showing probable maltreatment, and black showing severe maltreatment. Each graph shows how the combination of different social behaviors and different levels of MAOA affected adults differently. In nearly all the graphs, there’s a greater percentage of those with low MAOA activity that have social issues than those with normal or high MAOA activity. Also, regardless of MAOA activity level, subjects who suffered severe maltreatment also account for the highest percentage of social issues (Source).

As crazy as the impact of abuse and negligence is, it doesn’t justify anything. 1 out of 7 children have experienced abuse in their childhood, an estimated 5% of children will suffer the loss of one or more parents by the age of 15, and about 21% of children are bullied in middle and high school. Even though millions of children suffer, they don’t all turn into criminals–and they definitely don’t all choose to take someone else’s life. Ultimately, the connection between MAOA is correlative, not causative; there are many people who have a lower expression of MAOA, but precious few of them turn into the serial killers that haunt our nightmares.

(Source)

As I said before, there’s no “serial killer” gene–there’s a gene that can influence someone’s level of aggression and emotional control. Classifying people as “serial killer gene carriers” is a terrible idea for several reasons. Some people find themselves enabled by the knowledge of carrying a so-called “serial killer” gene as absolving them of responsibility for their actions. Determinism can be empowering, and often in the worst way possible. Consequently, knowledge of being a MAOA carrier can have the opposite effect–convincing perfectly ordinary, healthy people that they’re walking time bombs primed to explode. They might overthink their actions or go out of their way to avoid aggressive or violent behavior. Adrian Raine, a neurocriminologist, discovered that his genetic makeup was similar to that of the serial killers he studied. He went on to say that that discovery gave him “pause,” and caused him to reevaluate his past behavior and tendencies. While Raine didn’t turn into a serial killer, he went on to study them–but not everyone is as lucky. Labeling people as potential serial killers out of a misguided sense of genetic destiny is damaging; it can stigmatize healthy people, but it can also create serial killers out of once-normal people.

This brings me to an important point: serial killers aren’t born, they’re made. The social culpability for it bears a larger burden than any set of genes could. We’re a clear reflection of where and how we grew up, so there’s no point in assigning blame to our biological predispositions or environmental factors because its been known that we’re a product of our collective experiences. Ultimately, the solution to this problem is institutional. There are plenty of steps that we, as a society, can take to decrease the amount of crime and we should because, ultimately, every serial killer is a reflection of society and its flaws–just ask the town of Riverdale. 😉

References:

https://escholarship.org/content/qt5w51b7bg/qt5w51b7bg.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2987314/

https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/bornbad-1.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4776744/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4306065/ https://www.lehigh.edu/~mhb0/EnvtoPerson.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7144278/

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2013/may/12/how-to-spot-a-murderers-brain

https://www.nature.com/articles/219351a0.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4351151/