Principal Investigator. Professor. Soccer mom.

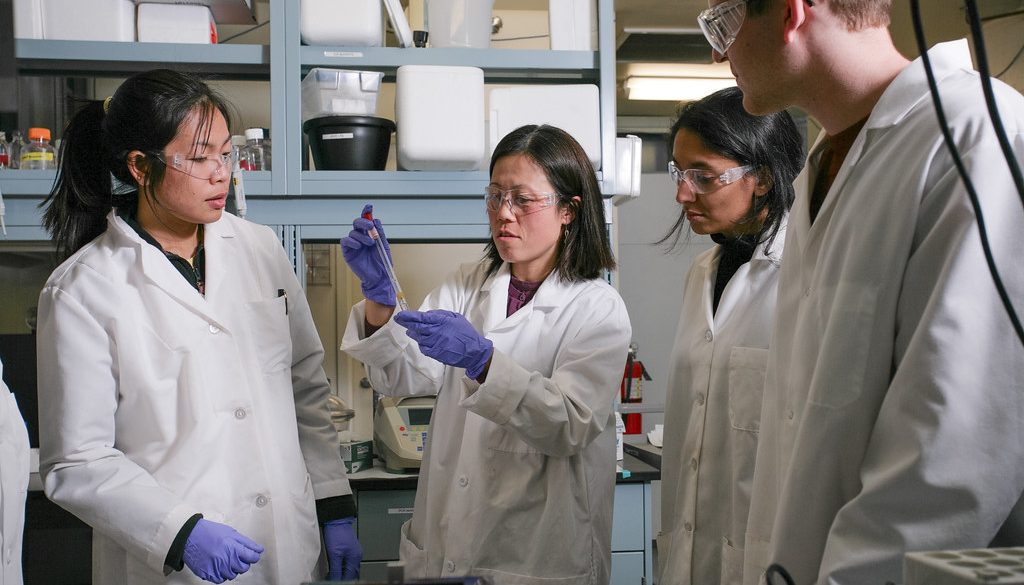

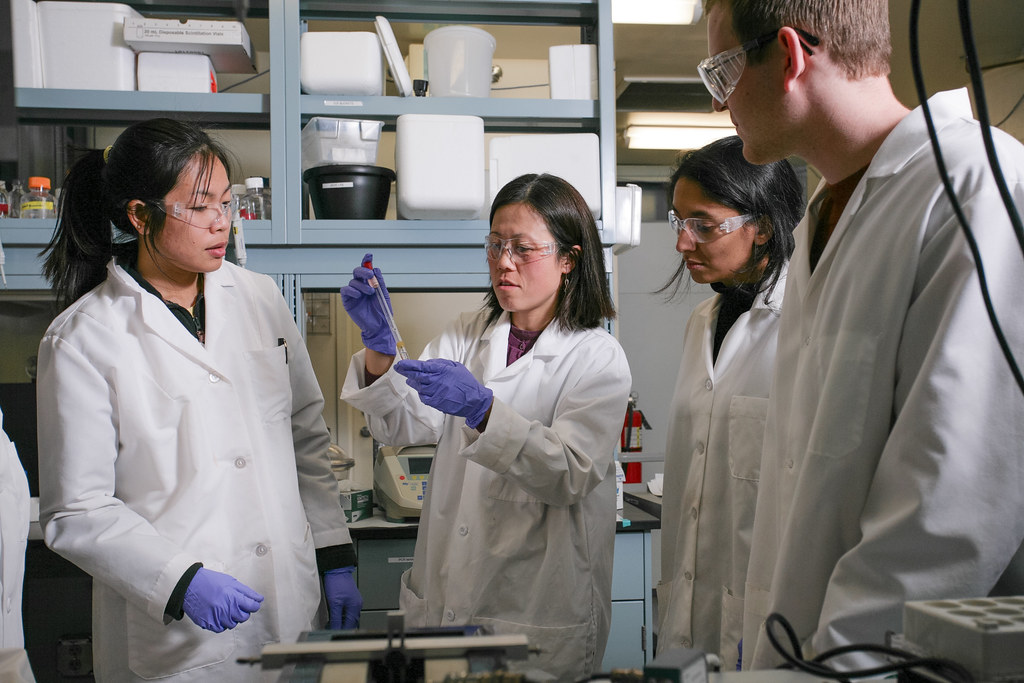

Dr. Sonya Neal is a principal investigator, or PI for short, at UC San Diego studying the nitty-gritty of protein quality control–how cells ensure that every protein produced is properly folded. A protein needs proper folding to achieve a specific shape that will enable it to do its job well. Misfolding of the protein can alter its shape, prevent the protein from functioning properly, and wreak biological havoc. Thankfully, there are mechanisms in place to get rid of misfolded proteins and maintain protein homeostasis. Dr. Neal and her team seek to uncover the steps behind the disposal of faulty proteins with the hope of understanding whether the disruptions to these steps will lead to diseases, and how to utilize that knowledge to develop treatment plans.

But let’s focus on Dr. Neal herself. What does life look like for Dr. Neal as a PI, professor, and mother? I had the opportunity to ask her myself and was astonished by her answer.

Wake up at 4am.

Write grants, manuscripts, etc. for two hours.

Go running from 6am-7:30am.

“Then,” as Dr. Neal puts it, “the craziness ensues.”

1) You must have a love for research. For Dr. Neal, she gets “science-induced insomnia” where she goes to bed thinking of experiments, and she can’t wait to share them because she loves answering biological questions. This love for research will be the core reason why you persist when experiments fail and when the job pay isn’t the best. With that said, there also has to also be an element of creative thinking when experiments don’t work out.

2) Being a PI means you have to be good at many things–patience, training mentees, teaching, communicating science, etc. Dr. Neal compared running a lab to running a business where the PI is the CFO and CEO.

3) Ask yourself: do you have a love for helping and mentoring students? Do you find fulfillment in teaching and seeing the people you mentor succeed?

TL;DR Academia is for those who love doing experiments, troubleshooting, and figuring out biological questions. You’re not going into this for money and you’ll have to assume many roles as a PI. You’ll be in a position to help students, so academia would be a great fit for you if you like doing that (Source).

She gets Kaden, her two-year-old son, ready for daycare and Elina, her thirteen-year-old daughter, for middle school. After taking care of her kids, Dr. Neal arrives at the UC San Diego campus for her PI and professor duties. On the days that she teaches a class, Dr. Neal teaches (obviously), goes to meetings, answers emails, and does anything else that requires little brain power. On the other days, she does research-related business such as writing grants and meeting with trainees and collaborators.

Outside of teaching and research, Dr. Neal does outreach for a UC San Diego mentorship program she founded, known as Biology Undergraduate and Master’s Mentorship Program (BUMMP). The program was born at the height of the Black Lives Matter movement in June 2020, and it arose from a desire to serve students, especially those impacted by the racial unrest. The goal of BUMMP is to help biology students of all backgrounds find their place in science by providing mentorship and resources to navigate their science careers. Dr. Neal is also part of committees that push forward initiatives to diversify the UC San Diego community. Although she does more than what is expected of an assistant professor, and gets some pushback for it, Dr. Neal loves what she does and is willing to carve out time in her schedule for projects that matter to her. To paraphrase Dr. Neal, she says “no” to some things in order to say “yes” to the more important things.

Towards the end of the day, Dr. Neal alternates with her husband for picking up their son from daycare and driving their daughter to soccer practice. Once she gets home, she cooks and does homework with her daughter. The day does not end until around 9pm when Dr. Neal finally has some time to wind down… but not too much time, since she has to sleep early to wake up at 4am every day.

I knew professors were busy people, but this takes it to the next level.

Before jumping into Dr. Neal’s backstory, I want to say a few things to help prime you, the reader. While interviewing Dr. Neal about her life, I couldn’t help but listen in awe. To me, her story was so raw and riveting. I felt privileged to be able to hear it firsthand from her, but I also felt the need to deliver her story in a way that captured Dr. Neal’s resilience and warmth (even if that meant going waaay past the word count). While reading, I hope that you can find encouragement and inspiration in her story–the struggle of finding a sense of belonging, the burden of paving a new path, and the significance of having mentors to guide you.

So grab your favorite drink, get comfortable, and enjoy!

Growing up in North Carolina, Dr. Neal recalls feeling insecure and uncomfortable in her own skin at a young age. Having a biracial identity as Black and Japanese allowed her to be part of two ethnic communities, but she didn’t feel completely wanted by either of them. Her Black relatives did not see her as completely Black, and she had very few opportunities to connect with her Japanese side of the family. This in-between experience led to an internal struggle with self-identity. When she was ten years old, Dr. Neal’s family relocated to Palm Springs, California to follow her father, who was stationed there for his Marine Corps duties. Even after leaving North Carolina, she still remembers the feeling of not quite fitting in anywhere.

In high school, like many students, Dr. Neal had no idea what she wanted to do for her future career. It was not until she took AP chemistry that her teacher noticed her interest in science. He encouraged her to apply for college and explained how she could use a chemistry or biochemistry degree to jump into fields like biotech or medicine. His advice was “enlightening,” especially considering the fact that neither of her parents was a college graduate. Having received no additional guidance, Dr. Neal decided to roll with that one piece of advice from her AP chemistry teacher and apply to different colleges. She ultimately got into UC San Diego as a biochemistry/chemistry major at Warren College, and thus began another journey.

When she first entered college, she was again thrown where she felt she did not belong. It was “imposter syndrome times 100,” Dr. Neal said. From her point of view, all her peers had come prepared–they knew what they wanted to do, they had connections, they had parents who were working professionals, they secured summer internships, yadda yadda yadda. And then there was Dr. Neal, who barely made it into UCSD and thought that that alone was a feat (and it was). She remembers meeting other students and thinking to herself, Oh my gosh, I’m nowhere near them, nowhere near their level.

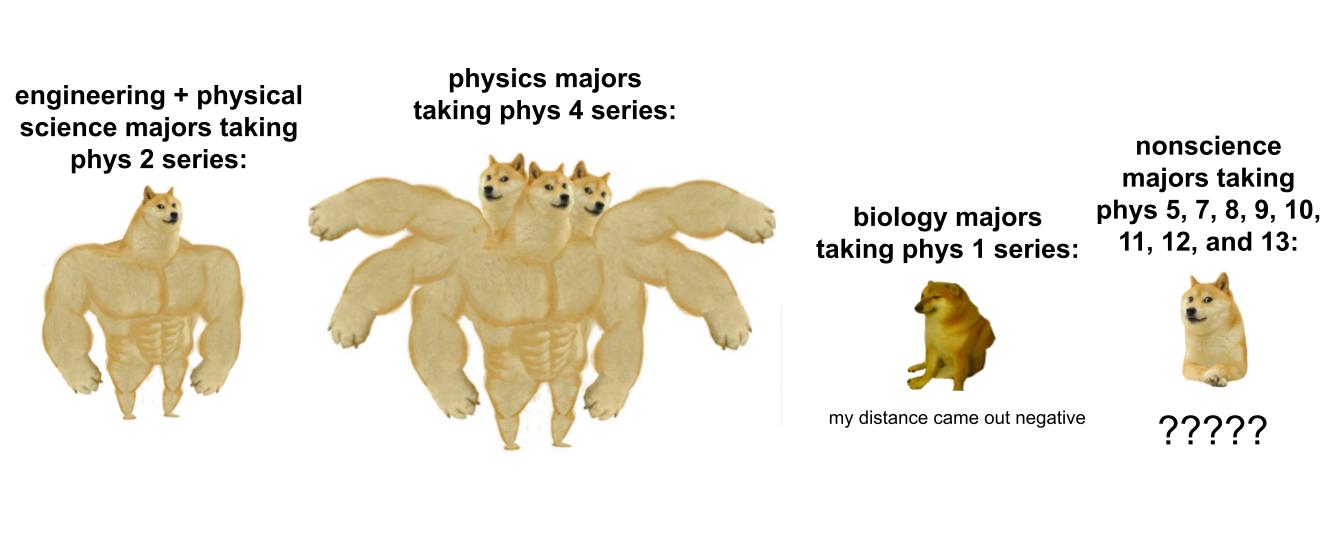

Her imposter syndrome was further exacerbated by a class that remains the bane of many college students today–physics. Her major required her to take the Physics 2 series, the same one required of engineering majors. It was hard, and I’m sure many students, including myself, can relate to that. I myself am currently retaking, and hoping to finish up, the Physics 1 series for biology majors, which is notoriously easier than the Physics 2 series and 4 series geared towards engineering and physics majors, respectively.

Physics itself is a difficult subject, but that wasn’t the only thing that made the class hard. It was also the rigor of courses, the large class setting with hundreds of students packed into a lecture hall, and the reality of being one of the few Black students on campus. All of these factors made Dr. Neal feel isolated, marginalized, and intimidated. She ended up getting a C in her physics class, and she confided in her mom about not feeling like she belonged at school.

So with all that she was facing, how did Dr. Neal get started with research?

After entering college, Dr. Neal was still unsure of what exactly to do with a chemistry degree. Getting into medical school was popular at the time (and I can verify it still is trendy to be pre-med if you’re a biology major here today), but Dr. Neal was not drawn to it. While walking through Price Center, she came across a flyer advertising UC Leads, a program geared towards under-represented minorities interested in doing research after graduation and getting a PhD. She read the flyer and was blown away by how people could get a degree by doing research and get paid to do research at other institutes. So, she applied for the program and got in. UC Leads helped get her foot in the door to academia.

Through UC Leads, Dr. Neal had the opportunity to work in two research labs: one in organic chemistry, led by Dr. Emmanuel Theodorakis, and another in biochemistry, led by Dr. Marilyn Farquhar. While she gained good research experience in both labs, she was drawn to biochemistry a lot more than synthesizing compounds in an organic chemistry lab. Then, Dr. Neal received another opportunity through UC Leads to do summer research at another institute. In her junior year, she spent a summer in Dr. Carla Koehler’s lab at UC Los Angeles to study the molecular mechanisms that occur in mitochondria, and she fell in love with the research. UC Leads helped Dr. Neal realize that she loved spending time at the bench and troubleshooting experiments.

Dr. Marilyn Farquhar, a renowned scientist and one of Dr. Neal’s PI advisors at the time, saw that she was a quick learner, had a good attitude, was a skilled researcher, and was persistent in troubleshooting. Dr. Farquhar told her that she had the potential to pursue a research career based on all these qualities. This encouragement, along with working in all three labs, confirmed Dr. Neal’s desire to pursue research.

Several months later, Dr. Neal graduated from UC San Diego and was accepted to UC Los Angeles’s PhD program, making her the first in her family to get a 4-year undergraduate degree and potentially the first to get a PhD. It was a very exciting time, and life at this point was going very well… until life threw a curveball at Dr. Neal.

She found out she was pregnant.

Dr. Neal was now forced to choose whether she should continue her graduate education or quit to focus on being a mother. Whatever she decided, she knew that she would have to be a single parent, and people were going to judge her for that. Going from the joy of being her family’s first college graduate to the uncertainty of what step she should take next was not easy. There were doubts from family, friends, as well as Dr. Neal herself. She wasn’t sure if she could handle grad school on top of being a single mother, and she was so close to giving up her chance to get a PhD. She thought, There’s no way I can pursue this.

Thankfully, when she was struggling to make one of the hardest decisions in her life, Dr. Neal received guidance from the three mentors whom she had worked with. She did not believe in herself and was worried about people judging her and they told her, “Who cares? You’re already in. Your foot’s in the door. Just go for it and if you can’t do it, at least you tried.” After intense deliberation, her mentors’ heartfelt advice and her family’s willingness to move to Los Angeles and support her solidified the decision to continue with grad school.

I asked Dr. Neal what she would tell her younger self if she could go back in time to that particular moment, and this was what she would say:

“Sonya, thank goodness you decided to push all the doubt aside and just go for it. I am so proud of myself for just doing this… I’m just so thankful that I was able to push that boundary and move it to the next level.”

Whenever she practices her daily gratitude, Dr. Neal always looks back on this moment because she was so close to saying “no,” but decided to push forward in spite of the pressures that came with single parenting.

While in grad school, Dr. Neal recalls being underestimated by others once they discovered she was a single mother. Labs that were initially interested in having her join their rotation subtly rejected her after learning of her situation. With no one willing to take her, Dr. Neal reached out to Dr. Koehler, whose lab she had done summer research in as an undergraduate. Having seen what Dr. Neal was capable of, Dr. Koehler agreed to let her rotate into her lab and support her in any way she could.

Back then, there was no maternity leave nor lactation facility, since many students did not have children, but Dr. Koehler lent her personal office as a lactation room and arranged to let Dr. Neal work from home for two months as unofficial maternity leave. Her advice to Dr. Neal was to stay organized. According to Dr. Neal, staying organized meant she had to plan each day down to the minute and be ten steps ahead of everything. Since she could only be in the lab from 6am to 2pm and she couldn’t work on the weekends, Dr. Neal had to be creative in the types of experiments she could perform. Dr. Neal mentioned that having her daughter Elina was a blessing in disguise, as the busy days pushed her to work efficiently. Also, if an experiment did not go well, it was nice to go home to her daughter as a “distraction” to keep work and personal life separate.

Even with this demanding schedule, Dr. Neal still loved research. Within five years in the lab, Dr. Neal was able to publish three papers and get a grant. She also had the opportunity to attend both national and international conferences and take Elina with her (with Dr. Koehler babysitting along the way). Going to grad school with a baby was not easy, but that never made Dr. Neal waver in her decision to pursue research. Rather, it was the microaggressions from other PIs that made it difficult to continue, but she persisted with her daughter as her main motivation.

After getting her PhD, Dr. Neal decided to do a postdoc instead of going into biotech, since a postdoc position would give her the flexibility she needed as a single parent and the option to choose between industry and academia. When applying for postdoc positions, Dr. Koehler suggested applying to work with Dr. Randolph Hampton at UC San Diego. When they met, Dr. Hampton didn’t judge her position as a single parent, nor see it as a setback. Instead, he saw her as a valuable scientist based on the work she did in Dr. Koehler’s lab. Dr. Neal was drawn to him for this reason, and she decided to apply for his lab.

Simply put, Dr. Neal was accepted into Dr. Hampton’s lab and made a discovery about protein quality control “with serendipitous luck.” Her discovery made her a competitive applicant when applying for faculty positions, but when she finally received interview offers from various institutes, she still couldn’t believe it. She still experienced imposter syndrome and thought, I don’t think I belong here. To this, Dr. Hampton told her, “What the heck. You are competitive, Sonya. You deserve to be here. I support whatever institute you decide to go to.”

1) Reach out to your professors as a first resort since you have weekly interactions with them. Make an effort to go to office hours whenever possible.

2) Graduate students can also be mentors. Keep in mind a mentor doesn’t have to be a professor or PI.

3) Check out the many programs at UC San Diego that offer career workshops, outreach programs, and seminars where speakers come in and speak to students. Consider sending a follow-up email that lets them know how their story or insight impacted you. If you’d like to, try asking for a one-on-one meeting with them. If they don’t respond, it’s okay. Be comfortable with not hearing back from certain people. You’re limiting yourself if you don’t reach out (Source).

Long story short, Dr. Neal decided to join the UC San Diego faculty. Now, she and Dr. Hampton are colleagues in the same division and section, with offices in neighboring buildings. Sometimes Dr. Neal still drops by his office to say hello and laugh. Even as a professor now, she still seeks advice from Dr. Hampton on how to be a PI and manage people. Dr. Neal shared that she was indebted to him and that she wouldn’t be in her position without his support.

Having been the beneficiary of mentorship from many people, it’s not surprising why Dr. Neal is so passionate about mentoring others. Mentors are important, especially when unexpected events happen in life and you need guidance. When I look at Dr. Neal, I see strength and tenacity, but this resilience was only possible with sincere advice and support from compassionate mentors.

For those wondering how to continue despite being different from others, I asked Dr. Neal to share her advice for you:

“Embrace your uniqueness. Embrace it, embrace it, embrace it because you are going to be at this level one day where you can be a role model for other students. For me, being a leader is being vulnerable and telling your own story. When you are unique, you have a unique story to tell. You’re a colorful person, and people are going to admire you. So just continue being yourself. Who cares what everyone else thinks about. You don’t fit into any norm. I sure as heck don’t fit that normal persona or that image that most people would say that a scientist or professor should look like. Of course, you’re always going to get the microaggressions from folks that aren’t used to that, but my endgame is just being at that platform where I can be the role model. If you have that end goal in sight, and you want to do the same thing, nothing else is going to matter. One day when you’re at that level, all the things that you went through, it all will be worth it.”

References

https://biology.ucsd.edu/research/faculty/seneal.html

https://www.bummpucsd.org/about

https://adminrecords.ucsd.edu/Notices/2019/2019-11-27-1.html

Thank you to Dr. Neal for allowing me to interview her and share her story.