If you study biology at UC San Diego (like yours truly), you will find that research plays a pretty big role at this university. Here by the temperate La Jolla seaside, there is a host of biological research labs located on campus and at the university’s surrounding research institutes. Some seek to uncover the mysteries behind complex root systems of plants, while others investigate potential solutions to Alzheimer’s disease.

It’s pretty cool to be a student at a research school, but do you ever feel slightly intimidated by someone (let’s say your professor) who has published an impressive list of research papers, many of them being cited a little more than once? Were they always this passionate about research? What were they like when they were college students? Did they also struggle with understanding mechanisms in organic chemistry? Through this series on the making of a researcher, I hope to humanize the stories of research scientists and understand their journey. Perhaps along the way, this series could also inspire those who have been mulling over the idea of getting into research but are not confident that they have what it takes.

With that said, let’s get down to business.

To kick off this series, I thought of my friend Breanna Lam, whom I met in a physics class during my freshman year. Although I ended up dropping the class shortly after the first lecture, I kept in touch with Breanna and watched her thrive in her studies. Currently, Breanna is on the other side of the country studying as a first-year biology PhD candidate at MIT. A look into Breanna’s time as a Triton sheds some light on one of the many paths to becoming a research scientist.

When Breanna came to UC San Diego, she had her sights set on medical school. Like many pre-med students, she volunteered at a hospital to gain exposure to working with patients in a medical setting.

However, the reality of this experience differed from her expectations.

While volunteering in the progressive care unit (PCU), Breanna witnessed many patients in pain. She found it difficult to converse with them since they were often too tired or too agitated to carry out a conversation. On top of that, the nurses that Breanna worked with were desensitized to their patients’ miseries, which made Breanna realize she would be emotionally drained as a physician in response to seeing her patient suffer continuously. This was not what she envisioned for her future, so Breanna decided to dabble in something else–research.

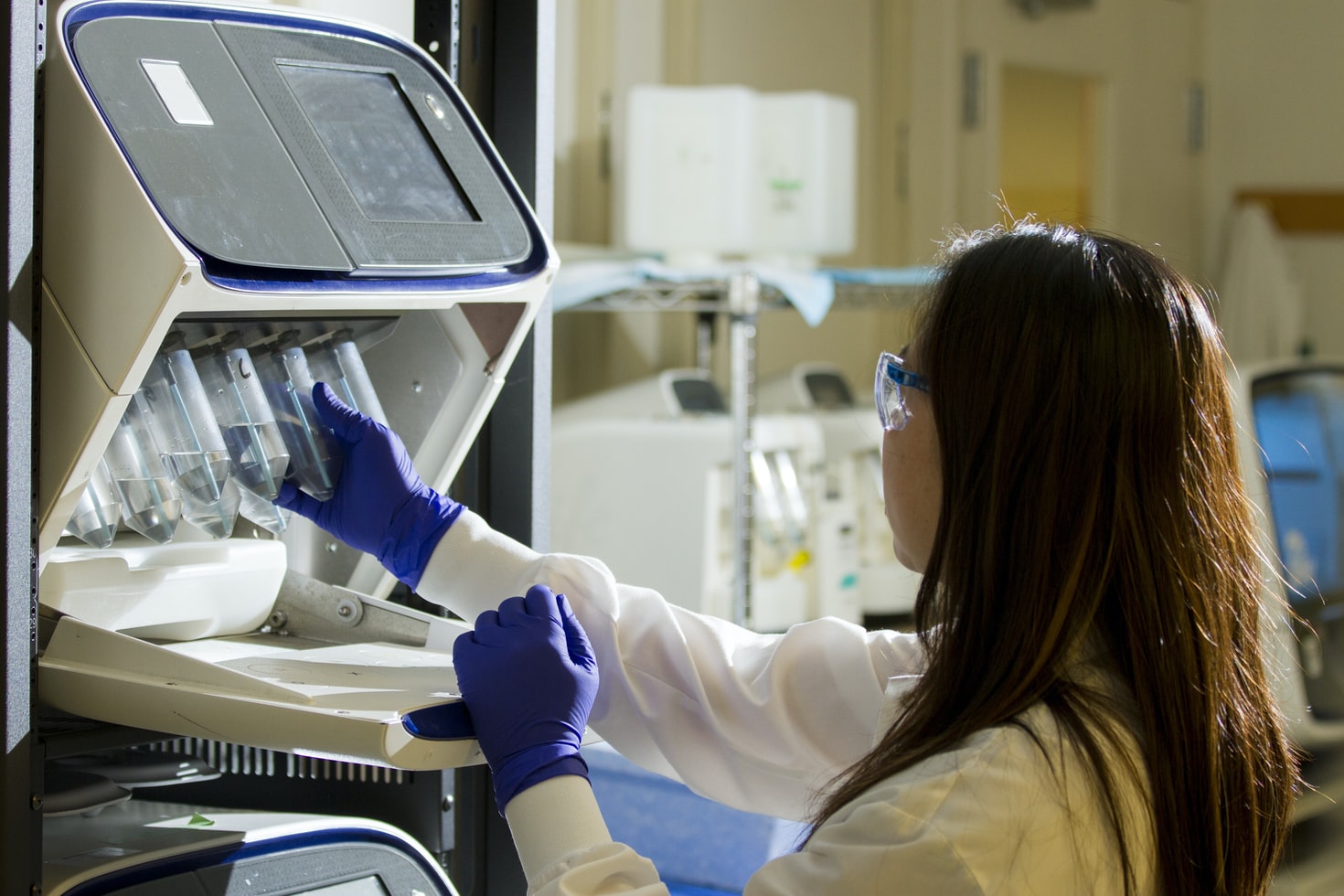

Around that time, Breanna was also volunteering in a research lab, and it helped her realize that she enjoyed spending time in the lab much more than in the hospital. To further explore what research was like, Breanna took part in the Regents Scholar Research Initiative, a program that pairs a freshman like Breanna with a faculty mentor and offers hands-on research experience. While searching for potential faculty mentors, Breanna took immediate interest in Dr. Randolph Hampton’s lab on protein homeostasis and was given the opportunity to work as an undergraduate research assistant in his lab.

At first, Breanna had no idea what she was doing. With no prior research experience, Breanna was faced with a steep learning curve. In addition to learning basic lab techniques like PCR and gel electrophoresis, there was so much scientific jargon that often went over her head. Breanna soon felt what many people feel when they start working in a lab–imposter syndrome. It took months of perusing through scientific literature and asking a ton of questions before Breanna finally obtained a decent understanding of the research project that she was working on.

Having very little hands-on lab experience myself (which is not surprising after taking most of my lab classes online due to the pandemic), I can empathize with Breanna’s feelings of inadequacy. I recently pipetted for the first time and performed my very first SDS-PAGE, a basic lab technique that separates proteins based on their molecular weight and can be used to, for example, analyze the purity of a protein sample. For me, understanding the theory behind the techniques was not difficult. Rather, the hard part was familiarizing myself with a lab environment, locating equipment and figuring out how to use them, and finding the most efficient routine for performing techniques.

Here were some of my thoughts when I was in my lab class:

Sharp wastes go in… this container.

I have no idea how to make this dilution.

What am I supposed to do now?

I made a bubble. Great, now I have to start over.

CAN I POUR THIS BUFFER DOWN THE SINK?!

You get the idea.

I quickly found that my lack of preparation, along with my limited experience with labs, were a great combo for raising my stress levels. After I was finally released from my lab class, I felt relieved but discouraged because I didn’t like feeling so lost. I learned my lesson and decided to come prepared the next time by thoroughly reviewing the lab manual and understanding the “why” behind each step before doing the experiment. My experience was probably more theatrical than Breanna’s, but it gave me a better idea of what she initially felt when working in a lab for the first time.

So, how did Breanna overcome imposter syndrome? Breanna gave credit to Dr. Matt Flagg, a former colleague who was a graduate student at the time, for helping her gain confidence in the lab. He patiently went over experimental protocols, explained the esoteric contents of research papers, and answered any questions that Breanna had, no matter how simple. Dr. Flagg’s investment into Breanna enabled her to grow as a researcher and acquire essential skills such as thinking critically, designing experiments, and writing proposals, all of which helped her in future lab work. As she gained more expertise in the lab, she became more confident in her abilities and the feelings of imposter syndrome eventually went away.

When asked what she thinks students should do to make the most out of their time in a lab, Breanna stressed that it was crucial for students to learn as much as they can about experimental design. Technical skills, like pipetting, are things that can be learned relatively quickly, but in order to really become a scientist, you must learn how to think like one. That means learning how to think critically and troubleshoot experiments. To do this, try talking to senior lab members, graduate students, and the PI about an experiment you want to do. Ask them if doing the experiment your way makes sense and if there was anything that they would do differently. Getting their input helps you get closer to thinking like a scientist. If you’re working in a lab, I hope this advice helps you!

Now, what was it about research that made Breanna enjoy staying in the lab more than at the hospital?

For Breanna, going into research allowed her to help patients in a way that physicians can’t. While physicians who prescribe treatments directly help patients, researchers help patients indirectly by focusing on understanding the problem and then deriving treatments and preventative measures for physicians to use. To put it another way, going into research meant that Breanna could work on solving the problems of today in the hopes of making them problems of the past.

While research and medicine have their own respective challenges, Breanna said she found the challenges of research to be more “forgiving.” If an experiment didn’t work, there would be opportunities to try again. Research gives Breanna the opportunity to think and work on solving a problem at her own pace instead of being pressured to find a solution within a limited time period. In the case of medicine, especially with lives on the line, there isn’t much room for experimentation or creativity.

These differences between research and medicine fueled Breanna’s passion for research and ultimately led her to pursue a PhD. At MIT, she can develop the skills she needs to take research to the next level.

What does Breanna want to do with her PhD? Assuming all goes as planned, Breanna hopes to work as a venture capitalist at a pharmaceutical company where she would be able to, in her words, “bridge the gap between academia and industry, fund innovative projects that can help society, and combine [her] interests in business and the life sciences.”

Her inspiration to pursue this unique path began one summer when she was first exposed to industrial research while interning at a pharmaceutical company. There, Breanna learned that much of the work in the pharmaceutical industry depends on findings from academia to develop products to help society. Many venture capitalists typically have business backgrounds and may not have the best judgment in determining which projects are worthwhile. Breanna’s science background would come in handy in helping her select ideas that are promising.

Prior to my chat with Breanna, I had never looked into this overlapping realm between research and business. Besides academia and industry, it’s clear research has other potential directions beyond those we normally think about.

I asked Breanna to share a final piece of advice to our readers.

“The most valuable thing you can do during your undergraduate career is gain new experiences and figure out what it is you want to do,” she said. “It’s incredibly easy to want to be a doctor, a lawyer, or any other career, but you won’t know if it is for you until you actually see what their day-to-day is like and experience it. For me, I was set on becoming a doctor until I realized that my expectations were wrong. Being able to spend time in a lab and do real research made my decision to pursue a PhD easier.”

Breanna’s story has shown me that being a research scientist does not mean you have to be insanely smart. While I know Breanna to be extremely intelligent, it also took a lot of hard work to get to where she is today. On top of that, a research scientist is not a self-made individual. Rather, it’s someone with a stubborn passion for learning who is not afraid to ask questions and seek advice from mentors.

References

https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2021-lifestyle-burnout-6013456?faf=1#4

https://www.phosphosolutions.com/pages/sds-page-demystified

For more advice from Breanna, feel free to check out her book titled “Demystifying the PhD Process” where she shares some insight on applying to PhD programs.