As humans, our waking mind is preoccupied with thousands of thoughts on a daily basis, some of which are so habitual and subconscious that we cannot fully acknowledge their existence. In fact, these thoughts may be occupying much more of our mind than we give them credit for, one notable example is beauty. Beauty may seem like a nebulous concept at first; but in reality, we unconsciously spend an extraordinary amount of time thinking about beauty in ourselves and others. Surprisingly, this isn’t a recent phenomenon: in the 4th century BCE ancient Greek philosophers were discussing the importance of beauty as a trait that paralleled moral characteristics (1). However, much of humanity’s endless chase for beauty is not just rooted in philosophy, but also neuroscience. In fact, beauty is considered to be an important aspect of evolutionary theory, and it provides some explanation about how the animal kingdom developed. Through a more nuanced understanding of the evolutionary role that beauty has played throughout human history, we can better reconcile the implications of certain standards in our everyday lives.

So, what is beauty exactly? With thousands of years of discussion it is difficult to come to a singular definition. However, philosopher George Santayana’s proposed definition is a good starting point. In 1896, he wrote “Beauty is pleasure regarded as the quality of a thing.” This appears abstract, but Santayana describes beauty as an objective quality, something like color or size, that is inherent to the object (1). After a lifetime of being told that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” it may seem strange that beauty has an objective quality. However, even science supports the idea that there is some objectivity to the contributions of beauty to evolution. One meta-analysis of 919 studies revealed that our beauty standards are relatively fixed both across and within different cultures, proving that there are some universally preferred characteristics (3). Some important factors that predispose us to perceiving a face as attractive include health, symmetry of the face and body, specific ratios (between eye distance for example), and facial color. Attractive faces are also defined as familiar because they tend to match the average features of what is in the population around us, especially when it comes to proportions (5).

How do these qualities play a role in evolution? After all, isn’t all evolution based on natural selection? If evolution is rooted in natural selection, then how can we explain the existence of male peacock feathers or a male lion’s mane? How can these attention-drawing attributes possibly be advantageous to survival? It turns out that Charles Darwin himself struggled with this question, writing in 1860 that the “sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail makes me sick.” (2) Peacocks were the ultimate enigma for Darwin, whose theory of natural selection fell short against the peacock’s beautiful and bright feathers.

From this, Darwin developed a theory of sexual selection, wherein the competition for mates of the opposite sex may driven partially by beauty. However, this understanding of beauty may not just be acquired for the purpose of reproduction as one study revealed that even 6 month old infants were able to notice beauty. The infants spent much longer periods of time examining the faces of “attractive individuals” (3). This means beauty isn’t just about sex, and it isn’t solely a behavior-driven phenomena. Some of our perception of beauty may come from physics (Einstein & relativity), chemistry (pheromones), and math (the Golden Ratio & symmetry) (5).

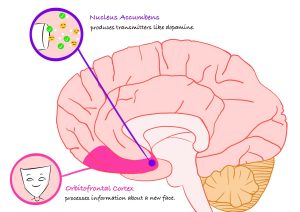

Studies like that performed on the infants suggest that beauty may be wired into our brain. The presence of beauty serves as a form of advertising for many species which serves far more of a purpose than just enabling love. Perceiving takes a cognitive load on our mind, but also yields important rewards. For example, as information about a new face is passed onto the orbitofrontal cortex of the brain, the nucleus accumbens (responsible for reward and reinforcement), will produce transmitters like dopamine (3). In fact, our brains are so hard-wired to recognize beauty that some studies suggest we process attractive faces much faster than unattractive faces(3).

One of the most fascinating aspects of beauty and evolution is the idea of costly signals, which are features that suggest reproductive fitness (3). In order to reap the benefits of these signals, the signaller must make a sacrifice or “cost” –these are often selected for by mates and passed onto subsequent generations in the “Green Beard Effect”. This effect explains why some animals possess such outlandish features such as moose antlers (3). These signals have been selected for repeatedly, change with time, and require nuance to detect. One example in humans is body size. As early as a century ago, a curvier figure was a costly signal that someone was wealthy and well-fed. In the modern day, a leaner figure may be associated with an individual having enough time, money, and discipline to dedicate to their figure. It is important to be aware of the fact that modern technologies allow us to falsely advertise certain costly signals. For example,someone with a fancy car need not necessarily be affluent, and beauty is easily manipulated with the recent rise in cosmetics. The user doesn’t incur as much of a “cost” as compared to true costly signals such as someone undertaking the mental and physical challenges of body building.

Not everyone is genetically blessed with features equivalent to beautiful peacock feathers. But for most of human history, people have sought to find ways to “secure” a mate. For the Ancient Egyptians, this problem was obvious, but the solution was transformative. Egyptians began adorning themselves with jewels and applying kohl to their eyes as a form of costly signalling. This may have inadvertently sparked what one research paper calls a beauty “arms race” that continues into the modern day (4). This is important as existing literature suggests that one’s perceived attractiveness impacts how they are treated.

The objective field of science is not immune to discriminating based on beauty, even if it is inadvertent. One notorious study in Nature highlighted that social scientists benefitted from being more attractive, while attractive natural scientists were perceived as having less credibility. This comes down to our own internal biases or the “Einstein effect.” We don’t like the idea that someone can “have it all,” meaning that they are attractive and intelligent, so we are more biased towards the less attractive natural scientists (6). This proves that our stereotypes can alter how we process beauty and limit it over time, which reinforces the idea that, to a large extent. beauty is out of our hands. We cannot truly conform to the ever-evolving media standards of beauty, but we can understand their origins by examining our own evolutionary relationship with it.

Illustrations by Yichen Wang

Sources:

2 https://www.nature.com/news/2011/110418/full/news.2011.245.html