If your high school sexual education program was anything like mine, you probably spent a class period or two watching a childbirth video or locating the fallopian tubes on a vague diagram of the female anatomy. Maybe your PE teacher rolled a condom onto a banana and called it a day. Or, if you were really lucky, you might have sat through lectures on abstinence and the criminal nature of sex before marriage.

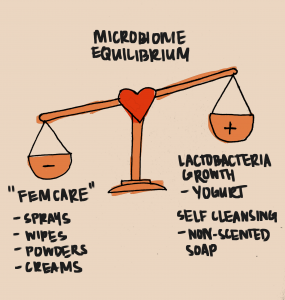

While this might have sufficed for public school’s educational standards, the sexual education of many young women is subsequently left to the hands of the $2 billion ‘femcare’ industry. This industry often neglects common and legitimate vaginal health concerns in favor of reproductive health and hygiene products. By endorsing ‘odorless,’ ‘hairless,’ and ‘fresh’ products, they have also created a culture of stigma and misconceptions surrounding vaginal health. By shifting our focus away from vanilla scented tampons, we can begin to address a foundational yet often neglected aspect of women’s health: the vaginal microbiome.

The vaginal microbiome consists of naturally occurring bacteria–the most abundant and important bacteria being Lactobacilli. Lactobacilli converts lactose and other sugars into lactic acid, which creates a protective, acidic vaginal environment with a PH of 4.5. Harmful pathogens are unable to thrive in such an acidic environment, which helps protect the vagina from possible sexually transmitted infections. This lactic acid-rich environment produced by Lactobacilli is also correlated with lower HIV rates due to the vagina’s acidic defense mechanism. In fact, one study looked at the rate of vulvovaginitis onset, a microbiome-related vaginal inflammatory condition, in women with a previous history of the infection. The experimental group was treated daily with 250 grams of Lactobacilli-containing yogurt and compared to a control group. After six months, the women who ate the yogurt everyday had a lower vulvovaginitis recurrence rate of 0.38, compared to the higher recurrence rate of 2.5 in the control group.

Studies have also shown that the vaginal microbiome composition can influence the quality of women’s fertility and reproductive success. Lactobacilli has proven critical in successful reproductive outcomes, as a recent in-vitro fertilization (IVF) study has found a positive correlation between a lactobacilli-poor microbiota and adverse pregnancies. Authors of the study concluded that, among other reproductive factors, microbiota lacking in lactobacilli can be considered a primary cause of implantation failure. In tandem with the lack of lactobacilli, other studies have focused on the effects of microbial colonization, or the occurrence of a higher population of unnaturally occurring bacteria. In a study of 110 women undergoing IVF procedures, researchers found a higher rate of successful pregnancy in the group with no excessive microbial growth, as opposed to the group with increased microbial colonization.

When the vaginal microbiome’s composition is thrown out of equilibrium, infections and other adverse conditions can arise, including Bacterial Vaginosis (BV), the most commonly diagnosed condition among reproductive-aged women. Women with BV frequently experience symptoms of unusual vaginal discharge and malodor. While current literature on the exact cause of BV remains uncertain, growing evidence shows that BV occurs when the normal, healthy composition of lactobacilli decreases and is replaced by other types of bacteria that do not produce lactic acid. Without lactic acid, the vaginal environment is no longer acidic enough to ward off harmful pathogens, therefore inviting infectious agents to cause adverse conditions.

Almost a third of women in the U.S. have experienced BV at one point in their lives, and one of the biggest risk factors is the common misconception that some popular feminine care products, including vaginal moisturizers, lubricants, creams, and cleansers, are beneficial to women’s reproductive and sexual health. In fact, when women purchase and use these reproductive health products, they unknowingly engage in improper vaginal hygienic practices that actually exacerbate BV. Despite the alluring advertising for vaginal sprays, wipes, and powders, these inorganic products are actually not hygienic at all. In fact, one research study on the effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal microbiome found that participants who used vaginal health products were approximately three times more likely to contract adverse health conditions, such as UTIs, yeast infections, STIs, and BV. This seemingly contradictory phenomenon occurs because chemically infused, inorganic hygiene products can completely disrupt the growth of healthy Lactobacillus bacteria, as well as strip the vagina of its protective epithelial cells, which form the layer of tissue that lines the surface of the vagina. As a result, the vaginal microbiome can plummet to an unhealthy, highly acidic pH level below 4.5.

Despite misconceptions about the proper way to clean vaginas, the answer is rather simple: doing nothing at all. Equipped with lactic acid, healthy microbes, and vaginal discharge, the vagina can independently protect its internal environment and flush out unwanted pathogens through discharge. In terms of cleanliness, professionals only recommend using non-scented soap and water gently on the vulva, the outer opening of the vagina.

Clearly, misconceptions continue to rule our common knowledge of the self-protecting, self-cleansing powers of the vagina. However, with increasing interest, funding, and research on the vaginal microbiome, there is hope that stigma surrounding women’s reproductive health–along with scented wipes, douching, and other invasive ‘hygiene’ practices–will soon be a thing of the past.

Sources:

- https://cusjc.ca/catalyst/project/shaming-the-vagina-the-psychology-and-pseudoscience-of-health-and-freshness-marketing/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3780402/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5865287/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1472648317301876#:~:text=In%20recent%20years%2C%20the%20health,supplementation%20have%20been%20shown%20to

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3780402/#R59

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3758931/

Illustrations by Diana Presas