When asked to describe her reaction when the weight of the COVID-19 pandemic set in, third year Kyla Laing said, “I don’t know how else to express it except I was lying in bed thinking, ‘I’m going to die.’”

For some, it may be hard to recall the red-hot panic they experienced back in March 2020. But for Kyla, not only was she transitioning into finals week like so many other students, but she also faced an increased risk for serious COVID-19 symptoms. Kyla, like 1.5 million people in America, lives with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and is considered immunocompromised.

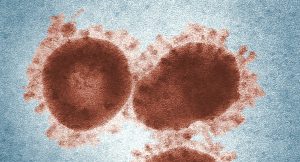

In autoimmune diseases like SLE, the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues which leads to tissue damage and widespread inflammation. How does this happen for SLE specifically? A mix of environmental and genetic factors can cause programmed cell death in the body’s tissues and release genetic material normally protected by the cell’s nucleus. The immune system will mistakenly label this free floating material as foreign and will try to inhibit their function by producing antibodies. Antibodies will bind to the “foreign” material and accumulate in tissues, leading to severe systemic inflammation.

As there is currently no cure for SLE, Kyla takes medication to suppress her overactive immune system and manage her symptoms including periods of fatigue, fevers, and joint pain. Here is where Kyla’s complicated Catch-22 is exemplified. Because the medication actively suppresses her immune response, her body’s defense is severely weakened if she is exposed to a pathogen, like the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19.

Understanding the dynamic nature of SLE symptoms is important to contextualize Kyla’s anxious response to the pandemic. Her symptoms “ebb and flow”, in which she will feel relatively healthy one week, and then be hit with fatigue or joint pain the next. Stress, exhaustion, injury, or exposure to viral illnesses are all environmental triggers that can resurface symptoms.

The perception of “health” is not so discrete either, as it lies on a spectrum of what a person believes to be their baseline. Many people consider that they are “healthy” if they aren’t physically sick. But the World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

Kyla’s own definition of health has evolved over time. Even though Kyla recognizes that she has a support system of friends and family, she has difficulty expressing when the symptoms of SLE are affecting her. She says, “I [would] feel like a broken record if I brought up every time I felt sick because I feel that way all the time.” Not only did her state of health change after the onset of SLE, but her baseline of what it means to be healthy evolved into her “always being a little bit sick.”

However, even though her symptoms are constantly affecting her, Kyla tries to achieve the WHO’s more complex definition of health in her daily life by addressing her physical, mental and social needs. She was a runner before her diagnosis in high school, and she still runs to this day. As a human biology major, she has worked as an IA and has been part of a lab even through quarantine. She also transitioned from a vegetarian to vegan diet early on in her diagnosis as another way to benefit her health, something that she believes may have aided into her speedy remission due to other patients’ testimonies.

SLE has redefined many aspects of Kyla’s life, which has made her appreciate her health to a much higher degree than she did pre-diagnosis. She notes that it can be difficult for college students to mull over one’s health if they personally have not experienced a severe health condition, near-death experience, or chronic illness. And college culture seems to place higher value on living life to the extreme, pushing our bodies to their limits both to satisfy our own curiosities and to conform to a rigorous school load.

Let us recontextualize this cycle of insomnia, stress, and lowered immune response and once more sink back into Kyla’s apartment at the end of winter quarter.

In order to maintain her definition of health, Kyla must take immunosuppressant medication, which decreases her levels of inflammation-inducing molecules. While over-inflammation causes many adverse symptoms of SLE, inflammation is also one of the body’s means of signalling the immune system to heal and repair damaged tissue. She is fully aware that her repressed inflammatory response makes her body susceptible to viruses, and the fear of contracting COVID-19 keeps her awake at night. At the same time, she has the mental pressure of wanting to do well during finals, which requires her to rest and remain healthy even though fulfilling these needs becomes impossible.

The combination of sleep deprivation, a demanding work environment, and deadlines create stress that is sensed by her brain, which signals her adrenal glands to pump out hormones. The release of adrenaline and cortisol activates her flight-or-fight response, and normal bodily functions are put on pause as her body prioritizes survival. And as the pandemic progresses, these hormones remain at high, irregular levels which create unnecessary inflammation and overwork the immune system.

Additionally, based on evolving data, stress is thought to be a trigger for SLE that exacerbates Kyla’s symptoms. This additive cycle of pandemic-related stress has her body working in overdrive, and if she were then exposed to the coronavirus, her immune system would not be able to meet the demands COVID-19 asks of the body.

Finally, she makes it through finals only to encounter an unempathetic response from the greater community in America. People are protesting the use of masks in the streets, and on social media, friends are ignoring social distancing guidelines to hang out. “It’s hard to get other people to care about your life,” Kyla notes. If people are not immediately affected by the consequences of the pandemic, it is easy to brush off the risks as a minor inconvenience. “Eating a restaurant, going to a bar… [this] is based on your desires of what you want to do for fun, but this is my life. I don’t know how to make other people care as much as I do.”

Part of this lifestyle stems from the privilege that many people have not had to redefine their baseline of health and realize its importance in response to chronic disease, which may be why they do not consider their health in such a high esteem that Kyla does.

But it can be difficult for a society with such an individualistic mindset to step outside one’s own lived experience. Kyla explains that, “Even people who are really close to you, of course they care about you, but they can never fully internalize or empathize with you. They can’t fully care about you as much as you care about you.” And in this individualistic society, you must become your own advocate.

So how might professors, allies, and friends better support people with chronic diseases during a pandemic? Kyla recounts when Professor Philbert Tsai, a physics professor at UC San Diego, demonstrated the qualities allies should aspire towards. In spring quarter, he communicated openly about COVID-19, demonstrated empathy and understanding for students’ situations, and provided accommodations for everyone whenever necessary. While professors and university staff cannot change the situation we are all in, they should continue to validate students’ experiences and vocalize global situations that could potentially bar a student from performing at their best. This attitude must continue into the upcoming quarters. Students may have “adjusted” to online learning, but that does not mean their hardships are entirely mitigated.

By allowing herself to be interviewed, Kyla has brought light to pertinent issues regarding accessibility, student wellness, and how we as a university can show our support. Sharing and solidifying experience on paper somehow makes the subject more concrete and tangible. And by acknowledging other people’s struggles with health, we can make decisions regarding COVID-19 that reflect our shared humanity.

Kyla Laing gave permission to display her real identity in order to shed light on SLE and how it has affected her experience at UC San Diego. If you would like to share your own experience with chronic illness, disease or disability, please feel free to reach out to akifer@ucsd.edu. And to Kyla, thank you. As the writer of this blog, I am truly honored that you shared your experience of SLE and COVID-19 with me. I hope to continually provide a platform for your voice as it deserves to be heard.

If you would like to learn more about SLE, the next blog of this series will describe Kyla’s journey through remission and what it is like to live with an invisible illness.

_______________________________________________________

Sources:

- https://www.lupus.org/resources/lupus-and-teenagers

- https://www.cdc.gov/lupus/facts/detailed.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3508331/

- https://www.health.com/condition/infectious-diseases/coronavirus/immunosuppressants-coronavirus

- https://www.lupus.org/resources/what-is-a-flare

- https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/frequently-asked-questions

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/immunosuppressive-drug

- https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/07/21/538377221/is-inflammation-bad-for-you-or-good-for-you

- https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/10/14/923672884/sleepless-nights-hair-loss-and-cracked-teeth-pandemic-stress-takes-its-toll

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0961203318817826?rfr_dat=cr_pub%3Dpubmed&url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&journalCode=lupa

Image Sources:

- https://unsplash.com/photos/s1jiWXu6lHU

- https://unsplash.com/photos/L0jLHqF7Q94

- https://unsplash.com/photos/Gvm7qlEae_M

- https://unsplash.com/photos/z7lTC8cFKKs