BY BAR YOSEF | UTS WRITER | SQ 2017-2018

[hr gap=”null”]

At UCSD, the art and biology departments are located on opposite sides of campus and have seemingly opposite goals, courses, and students. Art and science are in general seen as drastically different. However, if you look closer, art and science have many similarities and a deep historical connection. Both disciplines are a means of investigation that study nature and society by combining mind and hand in an attempt to gather information and apply it. In recent years, the connection between art and science has manifested in BioArt, in which artists use living organisms in their practice. It is also a connection that goes back centuries and may be most strengthened by art and science’s mutual exploration of life.

The relationship between art and science is perhaps best exemplified by Leonardo da Vinci. An innovational painter, da Vinci was also interested in various subjects including sculpting, architecture, music, mathematics, anatomy, and engineering. He is regarded as the epitome of a “Renaissance Man,“ someone of “unquenchable curiosity” and “feverishly inventive imagination” (Gardner 1970). Da Vinci studied physiology and anatomy in order to create paintings that accurately depicted human gestures and expressions. Beyond the canvas, he made contributions to many areas of science and technology. As a Christian, he believed that both art and science were a means to a higher spiritual truth.

The Impressionists and Post-Impressionists of the late-19th and early-20th like Vincent Van Gogh and Claude Monet were concerned with the effects of color and light physiologically and psychologically. Monet is widely regarded as the greatest nature painter in modern history. Through loose brushwork and composition, or the arrangement of elements, Monet sought to create an “impression” of nature. This impression is precognitive, meaning that it is before the mind identifies what it sees and converts it into memory. In Monet’s painting, On the Bank of the Seine, Bennecourt (1868), his fiancé looks down at the reflections of the houses and trees in the river. The upside down reflections symbolize the process of seeing. Light enters the eye and is inverted and projected onto the back of it, where the brain processes the information into an image. The moment Monet captures, between impression and perception, is known as the contingent moment, and conveys the sense of time passing and landscape changing. This concept can be related to Einstein’s theory of relativity, which asserts the contingent nature of observing reality.

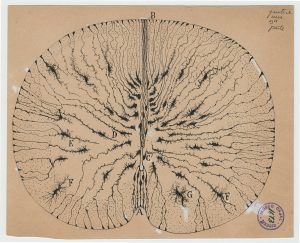

As artists use science and technology to create innovative works, scientists in turn adopt artistic techniques and ideas into their research. Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the father of modern neuroscience, did revolutionary research into the microscopic structure of the brain. Most seminal were his drawings of neurons that earned him the Nobel Prize for physiology and medicine in 1906 and are still used today. Ramón y Cajal made his drawings based on microscopic examinations of stained brain tissue, a novel method for his time. However, this most recent example is one that Maura C. Flannery, professor of math and computer science at St. John’s University, may criticize.

In Biology & Art: An Intricate Relationship, Flannery describes that the relationship is too often a “one way street“ in which artists are influenced by research or scientists create illustrations, like Ramón y Cajal. She advocates for a relationship that is a more “seamless whole,“ exemplified by Jonathan Kingdon’s zoology research. Kingdon, a zoologist and artist, drew pictures of the animals he studied. He believes that drawing is superior to photography because humans don’t see like cameras do and drawing forces one to pay attention to every detail.

Viewing nature itself as art is a centuries-old concept. This can be seen in nature printings of plants and fish. It can also be seen in artistic representations of nature that, like Kingdon’s drawings, can be informative. One area is glass art, which is more realistic because they are three-dimensional, transparent, and liquid. Glass art is particularly good for a different perspective on the microscopic and marine worlds.

More recently, artists have begun to move into laboratories by assuming assuming the role of scientist, particularly in topics relating to biology, in BioArt. This shift towards manipulating life as part of artistic practice can be seen as a continuation of an exploration of life that has always been a central focus of art, exemplified by Da Vinci’s anatomy paintings and Monet’s nature landscapes.

“What I find particularly interesting is that the entire history of art is actually pervaded by allusions to life, representations, imitations and simulations of life, and now manipulations of it too. From this perspective, the whole of art history is also the history of what’s alive. When you consider the early anthropomorphic statues and hydraulic automatons from Byzantium, and the definition of a work of art itself as an organism, and extrapolate this line of reasoning all the way to so-called genetic art, then you realize that this fascination with that which is alive has always been at the core of art,” said Jens Hauser, curator, scholar, and journalist.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

“the whole of art history is also the history of what’s alive”

___________________________________________________________________________________________

BioArt is not aesthetic, but conceptual, meaning that ideas are central. It often deals with synthetic biology. BioArt can also include art that uses imagery from medical and biological research. It often explores the ethical issues and controversies of the life sciences, and evokes humor and shock. It is a social response to the scientific practice of biology and is subjected to the same standards as the laboratory when artists use living organisms. It raises questions of what can be done in the name of progress for humans, as well as what it means for something to be alive. This practice emerged in the late 20th century and gained popularity in the early 21st century.

A controversial example is Eduardo Kac’s GFP, the first transgenic artwork. Kac coined the term transgenic and defines it as “a new art form based on the use of genetic engineering techniques to transfer synthetic genes to an organism or to transfer natural genetic material from one species into another, to create unique living beings.” Kac injected an albino rabbit embryo with green fluorescent protein, or GFP, to make it glow in the dark. He transformed a laboratory object into a social object and asked the questions of what is justifiable for an artist to do and how far will humans go in artistic and scientific practice. The work was created in conjunction with the National Institute of Agronomic Research in France, but sparked criticism from other genetic engineers, who found the work unneccessary. Kac’s many intentions for the work may have been lost on them.

One goal was to provoke an ongoing dialogue between professionals in various disciplines and with the public, as well as interspecies communication between humans and the transgenic animal. Another was to explore the scientific topic, particularly to subvert the reductionist hegemony of DNA as the creator of life by creating a more nuanced dialogue around the relationship between genetics, organism, and environment. Kac also wanted to examine the concept of what is normal, pure, hybrid, and “other,” as well as promote respect for the life of transgenic animals. Finally, he wanted to expand the boundaries of artmaking to include the manipulation of life.

The work can be viewed as an attempt for society to understand science through art. In an age when the public lacks trust in scientists, in part due to its increasing complexity, and the government, under the Trump administration, is withdrawing funding for it, fostering this understanding is important. By combining art and science, Kac challenges the notion that art and science are opposites and strengthens the connection between the disciplines. Not only has he made the public aware of this connection, but also challenged the hierarchy that, from the perspective of scientists, makes science more worthy of using GFP than artists. Perhaps artists, as demonstrated by Kac, are in fact more capable of provoking thought and understanding of scientific techniques.

Artists like Kac are beginning to subvert the dichotomy between the “subjective“ and “objective“ disciplines. They are designating art as a legitimate field of knowledge production. In academia today, interdisciplinary seems to be a buzzword. However, in order to return to the spirit of Da Vinci and the Renaissance, which integrated all disciplines, we may need to not only collaborate across disciplines, but alter the way we differentiate between them altogether.

Sources

Gardner, Helen (1970). Art through the Ages. pp. 450—456.

http://www.artic.edu/aic/education/sciarttech/2a1.html

“Biology & Art: An Intricate Relationship”

http://www.npr.org/sections/13.7/2017/01/20/510528975/the-art-of-the-brain-on-exhibit

https://www.aec.at/aeblog/en/2015/06/02/es-gibt-keine-bio-art/

http://www.ekac.org/slawson%203.html