LIAM HUBER | BLOGGER | SQ ONLINE (2016-17)

How Flowers Overthrew the World’s Reigning Flora

and Reshaped the Biosphere, Befuddling Botanists to this Day

Having outlasted the 2016 dumpster fire, it would be nice to report that 2017 will be less lousy. Unfortunately, only a few weeks in, this does not look like it will be the case; between impending political implosions, mounting UC tuition hikes, and shorter seasons of Game of Thrones, there’s not a lot to look forward to in the new year.

You can, however, find solace in the fact that you are not a Torrey Pine. Those scraggly conifers growing on the northwestern side of campus are not only trees–which I imagine must be pretty boring–but are also endangered trees. Given both these factors, you have to wonder how the Torrey Pines deal with such a sensation of powerlessness and depression.

The pines’ plight is nothing new; they, and all other conifers, are the losers of an evolutionary world war that wracked the forests and fields of bygone supercontinents. Emerging from the fallout was a new plant power, one which would basically define the biosphere in which you and I live.

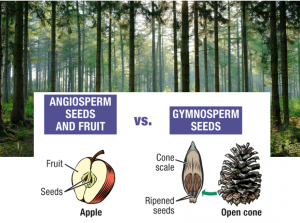

All seed-bearing plants fall under two categories: angiosperms and gymnosperms. An angiosperm, or “container seed,” has a fruit surrounding its seed, or embryo. A gymnosperm, or “naked seed,” does not. Yes, the place you go to work out comes from a Greek word for naked. (Source) (Source)

Taking Root

While watching a fern perform photosynthesis is not exactly the most exhilarating experience (for now, Planet Earth will stick with orcas annihilating some poor sea lions), it is true that plants, as a kingdom, do pull off one or two interesting things every couple hundred million years. The most recent episode of botanical upheaval happened in the furnace of the Mesozoic Era, that time on Earth that spat out clades similar to how you, as a freshman, spat out liquor. In terms of diversity, however, the other children of the Mesozoic–like mammals and birds–didn’t come close to what the plant kingdom produced.

I’m talking, of course, about flowers. Flowering plants–otherwise known as angiosperms–did not exist until a stone’s throw back into geologic time. Today, however, angiosperms account for 90% of all plant species, having an inextricable impact on just about every ecosystem. The only biological clade that packs a more diverse punch are insects.

It doesn’t seem totally unreasonable that angiosperms were able to do this in that short a span of time. After all, mammals also evolved during the Mesozoic and have done some pretty impressive things since then–just look at us (alright, you might have to look outside your dorm… try watching the news–no, don’t do that). But here’s the thing: angiosperms attained their present diversity during the mid-Cretaceous period, when mammals were still struggling to out-scurry dinosaurs and when birds still had teeth. Fossilized flowers from around 125 million years ago would suggest that angiosperms went from one unruly blossom to world conqueror in roughly 40 million years.

All this evolutionary success, of course, came at the expense of the existing dominant plants, which during the Mesozoic were none other than the gymnosperms, like our pal the Torrey Pine. The question these conifers might be asking–and what many paleobotanists are wondering too–is what allowed the angiosperms to come out on top, and how it happened so quickly.

Pollination is how plants–specifically angiosperms–have sex. Sperm is packaged inside pollen (yes, your allergies are from inhaling plant semen) and delivered to partners via helpful animal bros, like the bee seen here… and you can’t even get your roommate to knock. (Source)

Growing Formula

Charles Darwin pondered the same question. In fact, he was rather tormented by it, since he saw the rapid diversification of flowering plants as evidence against natural selection, which is necessarily a slow process. He referred to it as the “abominable mystery,” and, to solve it, he proposed that flowering plants had popped up on a lost continent and, from there, spread to places that scientists had studied, giving the impression that angiosperms had evolved out of nowhere. This theory sounds like something I would have written at the end of my BILD 4 lab report, and Darwin knew it. He continued to lose sleep over the abominable mystery until a colleague suggested a pretty simple solution: coevolution. Specifically, the back-and-forth evolution between flowering plants and the insects that pollinated them might have allowed angiosperms to evolve more rapidly than expected.

This was a satisfactory answer for Darwin, who could rest easy knowing that his theory of natural selection would become the cornerstone of modern biology regardless of those pesky plants. Contemporary botanists know a bit better; those big, fancy flowers that attract insect pollinators appeared during the mid-Cretaceous, already too late to be of much use. Simply put, they were a product, not the driver, of angiosperm diversity.

Don’t go discrediting Darwin just yet; before you throw your biology textbook into the ocean, consider that modern biologists have also pinpointed the origin of angiosperms to around 200 million years ago. Biology’s founding father had been onto something; it’s just that the undiscovered ancestors had been hiding around the globe, not on some unexplored continent. The fossil record in the 19th century was pretty empty, and this was the ultimate reason for Darwin’s headache. You might recall from an earlier blog that a similar scarcity of fossil information led Darwin and others to rush to proclaiming Archaeopteryx as the missing link between dinosaurs and birds.

Originating around 200 million years ago gave flowering plants time to evolve according to natural selection, but it still doesn’t explain how they evolved so well.

The genus Amborella, seen here, represents a remnant of one of the very earliest branches of the angiosperm evolutionary tree. (Source)

Flower Power

It’s time to talk about meiosis–what you’ve been pushing into the back of your mind since BICD 100. Meiosis is what generates sperm and eggs in all eukaryotic organisms–read animals, plants, fungi, and so on. Meiosis, you might recall, sometimes screws up, thrusting together two chromosomes that were supposed to be separated. This leads to a polyploid organism with extra sets of chromosomes. In animals, this basically means you die. In plants, however, it can actually be a plus. In fact, scientists think that, roughly 200 million years ago, this fortune fell on some lucky shrub. This became a basal angiosperm, the forerunner of every flower and fruit that you have ever met.

An extra set of chromosomes meant more room for mutations as well as more available protein product. This is where we get all the fun stuff that we associate with angiosperms: primarily, flowers, which became the signature feature of the angiosperm lineage very early on. Keep in mind, however, that the “flower hypothesis” doesn’t really explain angiosperms’ success; these new plants had pretty much consolidated their grip on the planet before pollination would have become all the rage.

Another important adaptation, also made possible by having an extra set of chromosomes, was leaf venation. A 2009 study that looked at a bunch of leaf fossils found that, during the Cretaceous, angiosperms had accumulated many more veins in their leaves. More veins meant more water for photosynthesis, which meant more growth and more kicking gymnosperm-ass. This nutrient-based theory also suffers a setback, however; while angiosperms are better at collecting water, gymnosperms can compensate, since their needles collectively provide much more surface area than leaves would.

What, then, was the key weapon in the angiosperm’s arsenal? Scientists are still not sure. Most likely, certain adaptations helped flowering plants adapt in certain environments, while others helped in different environments. The abominable mystery still lingers, and botanists have a lot of work to do–which might encourage you to enroll in Plant Molecular Genetic and Biotechnology Laboratory (but if watching The Martian didn’t make you consider a degree in botany, I highly doubt that this blog will).

Another unlikely beneficiary of the angiosperm ascension. (Source)

Putting it Together

While scientists still don’t know for certain which traits enabled the angiosperm takeover, we are fortunate that something did. Our civilization today is as much a result of flowering plant evolution as it is of human evolution, considering that our agriculture consists almost entirely of these organisms. Everything from the bread on your table to the pumpkin spice latte that Starbucks will hopefully stop advertising now that the holidays are over (and yes, for Christ’s sake, a pumpkin is a fruit) is because of a shrub that, 200 million years ago, messed up meiosis.

Some confluence of adaptations–be it pollination or leaf venation or some other benefit–led angiosperms to nearly annihilate the reigning gymnosperms over much of the Earth. Here, though, lies one of the most intriguing mysteries: why did flowering plants apparently take mercy on their victims? Torrey pines might not be doing so well in San Diego, but in the northern taiga forests, gymnosperms are still partying like it’s 200 million years ago. Even if the cold weather and barren soil here are setbacks to angiosperms, it makes little sense that out of 350,000 tries, no species of flowering plant was able to become dominant in this part of the world. That might be a much-needed comfort to a Torrey Pine, and you can remind one of it if you ever feel a need to go tree hugging–just make sure to hide about anything you consume, since it will likely be a product of the plants that brought on their agony.

A fruit is the protective structure that grows to surround a fertilized egg, known as a seed. We typically think of the tasty, fleshy kind, but the painful burrs that stick to your hiking boots also qualify. (Source)

In summary for this week:

- Roughly 200 million years ago, some unassuming plant mucked up meiosis, giving itself an extra set of chromosomes. This gave its ancestors, the angiosperms, the genetic ammunition to take over the world by the finale of the Mesozoic Era.

- No single factor was solely responsible for the angiosperms’ awesome success, but pollination and enhanced nutrient uptake certainly helped in certain environs. There’s still a lot that paleobotanists haven’t nailed down about their evolution.

- Angiosperms’ success was great for humans, since our agriculture relies almost entirely off of them, and terrible for gymnosperms, who saw their forests overwhelmed by the invaders. Conifers are still dominant in the taiga of the far northern hemisphere, where, for reasons still unclear, angiosperms could never adapt that well.

[hr gap=”0″]

Some places where you can read more about this:

- Everything you want to know about Torrey Pines: https://torreypine.org/history2/torrey-pine/

- Evolution of Angiosperms: https://www.boundless.com/biology/textbooks/boundless-biology-textbook/seed-plants-26/evolution-of-seed-plants-158/evolution-of-angiosperms-620-11841/

- The Abominable Mystery: http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20141017-how-flowers-conquered-the-world

- Origin of Angiosperms: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18559813

- Game of Thrones Season 7: http://screenrant.com/game-of-thrones-season-7-episodes/

Since a picture source is worth a thousand blogs:

- http://cdn.phys.org/newman/gfx/news/hires/2014/bee.jpg

- https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/sites/gateway/files/Noogoora%20burr%20Xanthium%20strumarium%20burrs_DAFWA.jpg

- http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-QRPK8EGe4vs/UOU9uJ6o8ZI/AAAAAAAABhI/ZKOW1uZVVZw/s1600/Angiosperms%20and%20Gymnospserms%20Differences.gif

- https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/564x/b6/b2/31/b6b2310a3b661b5821f8c55f00538484.jpg

- http://weknowyourdreams.com/image.php?pic=/images/forest/forest-07.jpg

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/26/Amborella_trichopoda_(3065968016)_fragment.jpg

- http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20141017-how-flowers-conquered-the-world