I look up amidst my violent coughing fit to see my roommate armed with hand sanitizer, a box of Lysol wipes, and an all surface cleaning spray. It’s week four. Half of our suite is already sick, the other half awaiting the inevitable. Twenty minutes later, we have cleansed every surface in the suite, down to the door knobs and fridge handles. There are hand sanitizer bottles every five feet, a large tub of Lysol on the table. We feel safe and self-assured. In the fight against bacteria, antibacterial products will emerge triumphant.

Or will they? Colds and flus are caused by viral infections, not bacterial ones, and most such products have yet to be proven effective against viruses. In December 2013, the FDA introduced a new rule demanding that manufacturers present data to support the effectiveness of antibacterial products. Studies following this rule indicate not only that antibacterial products are not as effective as claimed, but also that they may be adding to antibiotic resistance. The pressing concern is that in using antibacterial products, we are breeding super-bacteria.

Antibacterial soaps and sanitizers kill bacteria that are mostly benign, leaving behind the stronger, more dangerous ones with genetic mutations that make them immune. So while reading the label reassures us in that the product kills 99.9% of germs, the remaining 0.1% often have a resistance to the substances designed to kill them. They can then pass those mutations onto a new generation of disease-spreaders. These stronger bacteria are then the only ones that reproduce, which in turn increases the population of resistant bacteria, leading to the need for stronger and stronger sanitizing products.

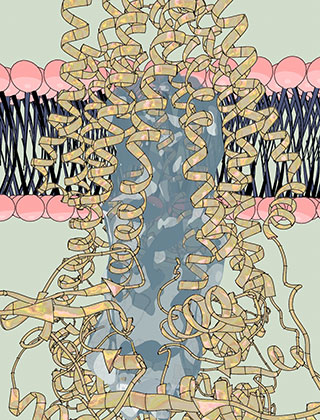

The biggest concern of all is this: by exposing bacteria to the triclosan present in most hand sanitizers, we allow for an increased activity in cellular pumps that the bacteria use to eliminate foreign substances, and contribute to the rise of antibiotic resistance. In effect, this means that in addition to aiding natural selection by allowing mostly resistant bacteria to survive, we may also be helping remaining bacteria develop a resistance.

In waging a war against bacteria, we strengthen them. This could contribute to what the UN Dispatch is calling a “lesser-known apocalypse”, a post-antibacterial era in which we have no drugs that work against antibacterial infections. So how do we stop it?

As demonstrated in a review of over 27 studies published in the Oxford Journals, non-antibacterial soap and water have proven to still be the best method of preventing the spread of disease. These studies showed that, “soaps containing triclosan within the range of concentrations commonly used in the community setting (around 0.3%) were no more effective than plain soap at preventing infectious illness symptoms and reducing bacterial levels on the hands.” Similarly, a study published in the Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy in 2015 demonstrated that antibacterial formulas did not kill any more bacteria than traditional soap and water even after 20 seconds, which is the amount of time that the World Health Organization recommends for hand washing. Several laboratory studies also evidenced triclosan-related cross-resistance to antibiotics among different species of bacteria, although it has not yet been determined how long it takes for this resistance to emerge.

While more research is required in order to gauge how long it takes for this resistance to develop, the fact remains that running your hands under water for even 20 seconds tends to be significantly more effective in removing microbes than using chemicals. This is because the point at which an antibacterial product surpasses standard soap in the amount of bacteria it kills is after nine hours of leaving the solution on – an inefficient amount of time to expect one to wash their hands.

So feel free to grab an alcohol-based hand sanitizer for the road, and use every sanitizing station you see at a hospital. And, remember: bacteria can’t develop a resistance to good old soap and water.