CHERYL PATEL | BLOGGER | SQ ONLINE (2014—15)

August 26

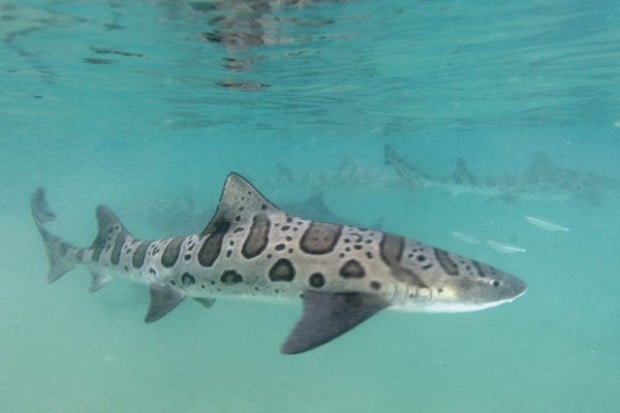

Dozens of pregnant leopard sharks gather in the warm, shallow waters off the coast of La Jolla in the late summer / early autumn. That’s why I was sitting on my paddleboard for a whole two hours, using it as a boat while I continually reapplied sunscreen to my exposed skin. There was this great photo online of leopard sharks congregating, and it was taken from an aerial point of view so that each shark looked like a dark, short streak painted into the clear water. Of course the image quality from a news helicopter did not do the scene justice, so I decided to get my own photos.

Getting a closer look at these fish was going to be easier than commandeering a helicopter; I got my friend, Andy, from the Birch Aquarium to come out with me so I could possibly touch the sharks as well. “Since sharks are fish, they have scales, just like fish do. But if you try to pet a shark from tail to nose, your hand could end up getting cut up,” he told me while we were waiting together on the water. This applies to all sharks.

It was important that we were on the water during the hottest part of the day because these female sharks search for warm waters. They usually do this when they are pregnant to keep the pups inside them warm, much like a mother bird sits on its eggs to regulate their internal temperature. Under the glaring sun, the only solace I had was to keep my legs dangling over the board.  I wasn’t scared that any stray sharks would come take a nibble at me; leopard sharks are bottom feeders, so they stick to swimming right above the sand and using their noses to feel around for clams, crabs, fish, and shrimp.

I wasn’t scared that any stray sharks would come take a nibble at me; leopard sharks are bottom feeders, so they stick to swimming right above the sand and using their noses to feel around for clams, crabs, fish, and shrimp.

Excitement bubbled through me as I first saw the shadows gliding through the water under me. They were beautiful. It wasn’t long before every square meter had at least two sharks in it. That’s when Andy slowly slipped off his paddleboard and stood in the water. It came up to his chest. “You gotta let them get used to you,” he said, stretching his arms over the still surface of the water. After a good ten minutes, he began his attempts to catch one of the females. I resisted the urge to squeal when he pulled one out of the water. It was almost three feet long and squirming every few seconds to escape Andy’s grip. Paddling over, I held my breath and I touched the smooth gray skin.  Up close, the leopard pattern on the shark was vibrant. Andy dipped the shark’s gills into the water before bringing it out so I could take a couple of shots of it.

Up close, the leopard pattern on the shark was vibrant. Andy dipped the shark’s gills into the water before bringing it out so I could take a couple of shots of it.

“Most sharks have to continuously swim so that water passes over their gills. That’s how they get their oxygen. Leopard sharks are able to stay stationary on the sand and pump water over their gills to keep the oxygen flowing through.” Andy had gotten back onto his board and was randomly spouting facts at me about leopard sharks and other sea creatures as I moved around my board to snap pictures of the scene underneath us.  “I’m more wary of squid than I am of sharks,” Andy said. “Humans have given sharks such a bad rap, and we forget how incredible and ancient they are.” My hand languidly waved through the water as close to the sharks as I could reach while lying on the board on my stomach. They minded their own business enjoying the warmth, and my hand traced their movement whenever one swam by.

“I’m more wary of squid than I am of sharks,” Andy said. “Humans have given sharks such a bad rap, and we forget how incredible and ancient they are.” My hand languidly waved through the water as close to the sharks as I could reach while lying on the board on my stomach. They minded their own business enjoying the warmth, and my hand traced their movement whenever one swam by.

“They’re cute,” was all I said to him.