When we think of plastic in relation to the environment, heart-wrenching images of polluted seas, dolphins trapped in plastic bags, and sea turtles entangled in plastic rings with deformed shells often come to mind. However, within our own bodies, there exists a lesser-known concern: microplastics in the human bloodstream. Although researchers are still in the process of understanding the possible implications of this finding, scientists have already begun to identify the adverse effects microplastics have on human health, particularly on a cellular level.

Microplastics are tiny plastic particles, no more than five millimeters in diameter, that result from the production of commercial products or the breakdown of larger plastics. Additionally, microplastics can be categorized into two groups: primary microplastics and secondary microplastics. Primary microplastics originate from commercial uses, such as cosmetics and microfibers from clothing, whereas secondary microplastics result from environmental processes that break down larger plastic sources, including water bottles and synthetic rubber tires. Once dispersed into the ecosystem, both primary and secondary microplastics may enter the human bloodstream in a variety of ways, such as through the food and water we consume and the air we breathe.

While microplastics have been previously detected in human feces, it was only until this past April that Dr. Heather Leslie and Dr. Juan Garcia Vallejo of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam detected microplastics in the human bloodstream. In their study published by the Environment International journal, researchers collected samples of whole human blood from twenty-two healthy volunteers and measured the quantity of microplastics present by heating and filtering the samples to break down the components of the blood and isolate the microplastic particles. Following this process, the collected microplastic particles were identified and quantified using a mass spectrometer, a device that separates substances based on their mass. The study concluded that 17 subjects out of the 22, or 77 percent, carried an average of 1.6 µg/ml of microplastic particles in their blood after analysis.

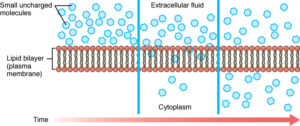

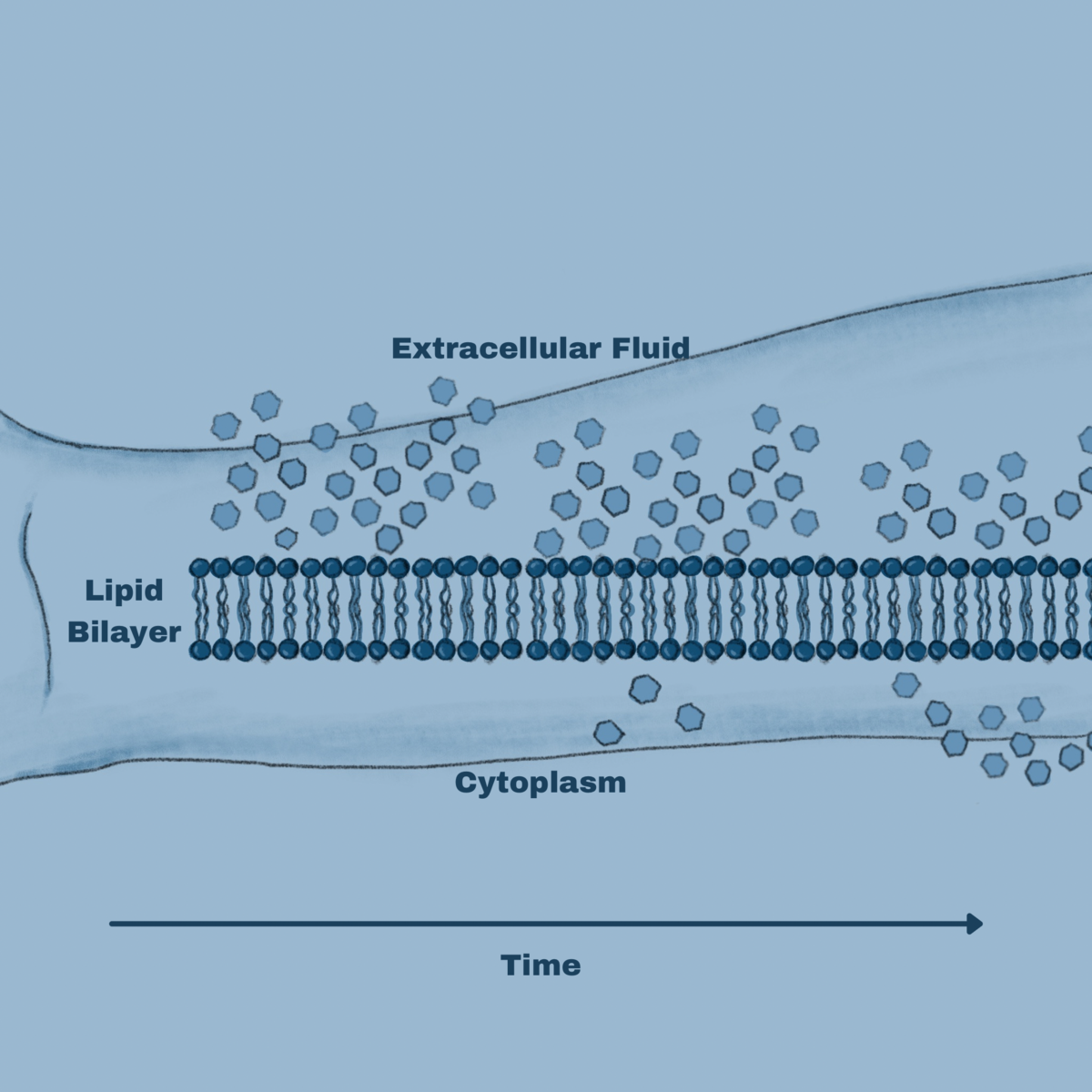

With this novel finding, several studies aim to explore the possible health effects of microplastics in the bloodstream. One possible effect of microplastics in the body is a destabilization of the plasma membranes in red blood cells. The plasma membrane, which separates and protects the interior of each red blood cell, critically regulates the entry of certain molecules, such as oxygen and nutrients, while preventing the entrance of toxins. When microplastics enter the bloodstream, however, each microplastic particle interacts with a portion of the plasma membrane. This causes the cell membrane to mechanically stretch, as microplastic particles, especially those less than 0.03 micrometers in diameter, may easily diffuse into and out of the red blood cells due to their small size. This alteration in structure significantly reduces the plasma membrane’s ability to maintain its shape, which in turn, may interfere with its proper functioning, specifically in regards to the transport of oxygen—the key role of red blood cells. With a decreased ability of red blood cells to transport oxygen throughout the body, the tissues of major organs that rely on oxygen to perform basic metabolic functions, such as the brain and the lungs, may face permanent damage.

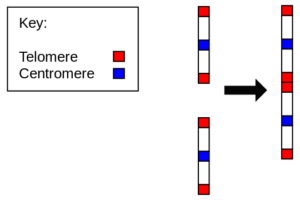

Microplastics in the human bloodstream may also lead to DNA damage within peripheral blood lymphocytes or white blood cells that travel through the heart, arteries, capillaries, and veins. When human peripheral blood lymphocytes were exposed to varying concentrations of microplastics in a study conducted by the National Institute for Research in Environmental Health, blood lymphocyte samples with higher concentrations of microplastics experienced higher proportions of breaks and fusions among their chromosomes. As a result, lymphocytes’ chromosomes may rearrange and impede DNA repair mechanisms, compromising genomic stability. This ultimately increases the likelihood of genetic mutations, thus increasing the risk of cancer development.

Although ongoing studies continue to explore the health effects of microplastics in the human bloodstream, studies thus far demonstrate that microplastics cause harm and must remain on the radar of public health professionals. From interfering with red blood cell function to damaging our cells’ genetic material, microplastics, while barely visible to the naked eye, have the power to alter the body’s physiological processes. As we continue to tackle the excessive amounts of plastic present in Earth’s vast, life-sustaining oceans, let us also focus our attention on “the ocean of our bodies:” our blood.

References:

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/microplastics

https://www.horiba.com/int/science-in-action/where-do-microplastics-come-from/

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/could-microplastics-in-human-blood-pose-a-health-risk

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412022001258

https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2104610118

https://www.mdpi.com/2079-4991/12/10/1632/htm

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abd1211

https://wordpress.org/openverse/image/2641d8e0-dcfa-420a-a9d1-0b19d3a36c6e