I’ll wake up as soon as the alarm goes off, when the phone lights up and starts vibrating on the table, even before the alarm begins sounding. This means that I’ll be the perfect roommate who’ll never annoy you with alarms every 10 minutes for an hour disrupting your sleep. On the other hand, if you’re someone who lets alarms ring early in the morning for more than a millisecond, it means that I’ll never get any sleep. In fact, it won’t even have to be alarms. A loud snore will be enough to make me open my eyes and kick my legs out of sheer frustration.

Snores. You know, that loud thing that drives you crazy in the middle of the night. Why do people do it? Can’t they just…not? How can a person be that persistently loud in their sleep? Why do snores happen?

The Airway Anatomy

To understand how snoring works, we first need to understand the anatomy of our airways. Your nose and mouth are connected by a chamber called the pharynx. Air flows through your mouth and nose into the pharynx, then down the trachea and into your lungs. In the back and roof of your mouth there is the soft palate, separating the mouth space from your nose space. Normally, it’s good that you have a strong, flexible soft palate, as the soft palate helps with breathing, speaking, and swallowing. We like those things, they keep you alive. When it comes to snoring, well, I guess you can’t have everything in life.

Biomechanics of Snoring

Researchers in England proposed two biophysical models of snoring. One is soft palate snoring, which has been observed in humans. Like I wrote earlier, soft palates are good, they help separate your nose from your mouth. The only problem: like its name suggests, the soft palate is soft. And sometimes, that soft palate can be too soft, which can disturb your breathing, especially when you inhale. During the day, muscles keep our airways open, but they relax when you sleep, allowing the soft palate to disturb your breathing. As the soft palate disrupts the flow of air, it flutters and hits/blocks the airway, causing the loud snoring sound.

Researchers in England proposed two biophysical models of snoring. One is soft palate snoring, which has been observed in humans. Like I wrote earlier, soft palates are good, they help separate your nose from your mouth. The only problem: like its name suggests, the soft palate is soft. And sometimes, that soft palate can be too soft, which can disturb your breathing, especially when you inhale. During the day, muscles keep our airways open, but they relax when you sleep, allowing the soft palate to disturb your breathing. As the soft palate disrupts the flow of air, it flutters and hits/blocks the airway, causing the loud snoring sound.

The other proposed model is pharyngeal snoring. As air flows faster, the air pressure within the pharynx (the mouth-nose chamber) is reduced. This follows Bernoulli’s principle, which says that higher speeds of fluids cause a drop in pressure (watch a cool demo here). In the airways, this happens until the walls of the pharynx eventually touch. But of course, you need air, so you continue trying to suck in air by creating a lower pressure in the lungs compared to the atmosphere. The difference in air pressure between the atmosphere and air causes the pharynx to quickly reopen, vibrating from the force of the air. This opening motion and vibrations cause the loud sound of snoring. This model is harder to observe, and therefore hasn’t been studied too closely in humans. However, other mammals (and only mammals—we’re the only ones with soft tissue in the upper airways) such as canines snore due to excess tissue in the pharynx, which may occur following this model of pharyngeal snoring.

Causes

So now you know how snoring works. But what causes it? Thankfully, snoring isn’t always pathological, otherwise it would mean that a lot of people I know are suffering from a respiratory disorder of sorts. Things like age, alcohol consumption, weight, and health all factor into how much a person may snore. If you’re tired, or had one too many drinks, your airway muscles may be a bit too relaxed, partially blocking your airway. Forcing air through the narrow pathway then causes rattling noises as your tissues vibrate, making you snore.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that snoring is never pathological. Snoring is often associated with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which has an estimated prevalence of 15-30% in males and 10-15% in females in North America. Several risk factors can contribute to developing OSA, including obesity and old age. OSA can be broadly defined as a type of apnea in which people stop breathing intermittently for 10 seconds or longer, at least five times per hour. This apnea (absence of breathing) occurs when your throat muscles relax too much in your sleep, blocking your airways. Along with loud snoring, OSA is also characterized by high blood pressure, morning headaches, and waking up choking or gasping. You might want to see a doctor if you have any or all of these symptoms, or if someone notices that you’re periodically not breathing during your sleep. As much as we like soft palates, we don’t like not breathing in our sleep.

Treatment: For snorers

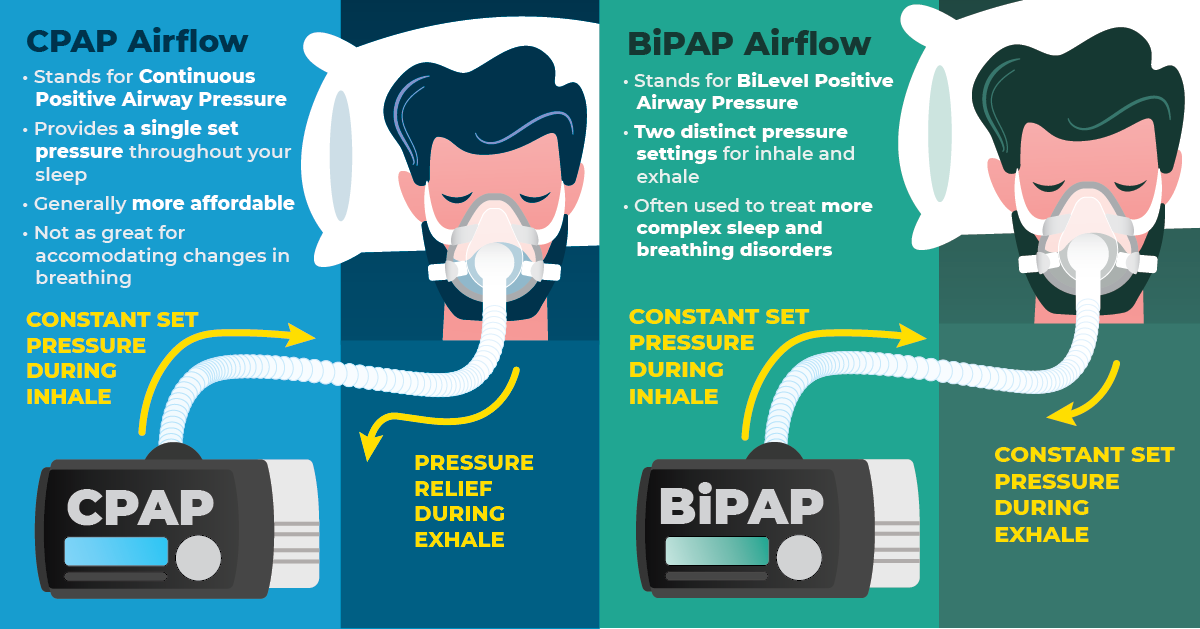

If you have OSA, positive pressure machines such as the continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) or bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) machine can be a non-invasive method of treatment. These machines require you to put an oxygen mask over your nose or mouth, which is then hooked into the machine, providing a positive air pressure environment for your airways. It’s basically pushing air in forcefully and keeping your airways open. It might feel clunky at first, but hey, at least you’re breathing!

If severe enough, you could also get different types of surgeries that permanently manipulate airway structures. This may include—but are not limited to—removing the tonsils, expanding the throat, or shortening the soft palate. Depending on the type of surgery, surgeries can be done by an ear, nose, and throat specialist (ENT) or an oral maxillofacial specialist. This can sound scary at first glance, but surgery is still a better option than leaving your severe sleep apnea untreated. After all, breathing is sort of an essential part of living. If you leave OSA untreated, you repeatedly don’t get enough oxygen during your sleep, which could lead to numerous health consequences. In case the lack of oxygen on its own wasn’t enough motivation for people with OSA to seek treatment, Michigan Health lists possible complications of untreated OSA, which include difficulty concentrating and heart disease.

Treatment: For sanity of people hearing snores

Now, what happens if you’re like me, and need a prescription for maintaining your sanity while others snore away? The Guinness world record for snoring is set at 93 decibels–compared to 50-60dB in an average snore–which is on par with blenders and lawnmowers (though I swear my parents can snore louder). Over 85 decibels for extended periods of time can cause permanent damage to the ears, but fewer decibels is still enough to cause permanent damage to my sanity. Needless to say, we light sleepers are the unwitting victims who also need treatment for other people’s snores.

Now, what happens if you’re like me, and need a prescription for maintaining your sanity while others snore away? The Guinness world record for snoring is set at 93 decibels–compared to 50-60dB in an average snore–which is on par with blenders and lawnmowers (though I swear my parents can snore louder). Over 85 decibels for extended periods of time can cause permanent damage to the ears, but fewer decibels is still enough to cause permanent damage to my sanity. Needless to say, we light sleepers are the unwitting victims who also need treatment for other people’s snores.

This blog introduces a various number of different products that may help with the noise. Among them are white noise machines, which help distract the ear from focusing on snoring, as well as the industrial earplugs. My favorite method at the moment? An extra pillow and foam earplugs (courtesy of Geisel Library—you can swipe an extra pair as you leave). With the earplugs in, I sleep on my side with a pillow on both ears, hoping that I’ll sleep soundly through the night. And when that doesn’t work…coffee. Lots and lots of coffee.