In 2017, Dr. David “Davey” Smith, an infectious disease physician at UC San Diego, and his research group launched the “Last Gift Study,” an end-of-life study that recruits individuals living with both HIV and a terminal non-AIDS related illness to investigate and identify the hiding places of HIV before and after death.

Most people are familiar with the concept of hide-and-seek, a popular children’s game in which the “hiders” conceal themselves within a given environment and the “seeker” searches for these hidden players. Indeed, many of us have fond memories participating in this game in our youth. However, this game is not only played by schoolchildren in the comfort of their own neighborhood circles–there are examples of the “hide-and-seek” tango in nature that determine the survival of both participants. With that in mind, consider this: what happens when the given environment happens to be our own bodies, and the “hiders” are deadly pathogens?

37.7 million individuals around the world are living with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Thanks to significant advances in medicine, a good number of these patients are able to live relatively normal lives. Nonetheless, scientists in the role of “seeker” continue striving to detect and identify where these potentially devastating “hider” virions are located.

Current HIV Treatment Options

HIV poses a major threat to humanity, particularly to those in developing nations suffering high poverty rates, a lack of barrier contraceptives, and scarce medical interventions. There are three stages of infection: acute, chronic, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). During the acute stage, where risk of transmission is highest, a large amount of HIV accumulates in the bloodstream. This causes occasional flu-like symptoms that align with the body’s natural response to infection by various pathogens. The chronic, or latent, stage is defined by little to no symptoms due to low levels of HIV replication. However, even if there is still a small amount of detectable virus in the blood, HIV is still infectious to other individuals, particularly during the exchange of bodily fluids such as blood or bodily secretions.

AIDS, the final stage of HIV infection, is characterized by a severely damaged immune system that facilitates typically low-pathogenic microbes to take advantage of the host’s impaired immunity, eventually causing additional infections. Fortunately, few individuals in the United States progress to this third and final stage due to the prevalence of antiretroviral therapy (ART), which has transformed HIV infection from a death sentence into a chronic condition. ART reduces the amount of HIV in the blood to undetectable levels, making it so that HIV+ individuals are no longer infectious to others. Though it is not a cure, ART does prevent HIV from replicating, locking the virus in its chronic stage.

Despite the considerable success of ART, many challenges remain in developing additional therapeutics for HIV. Unlike acute infections such as influenza, HIV remains within people for their entire lives, even when not actively replicating. In particular, HIV searches for convenient pockets of the host’s body to hide in. One such location is brain tissue, presenting a dilemma to potential therapeutics because antiretroviral drugs cannot cross the blood-brain barrier. Thus, for a cure for HIV to be developed, it will be imperative to eliminate these HIV reservoirs in patients before ART is ceased.¹ However, since HIV is never truly removed from the hidden reservoirs in the body during ART, the virus rebounds rapidly if patients stop taking ART for even a short time, making it difficult for researchers to pin down where exactly HIV populates the body during the latent stage of infection. Thus, it is necessary to thoroughly analyze tissue samples from all over the bodies of HIV patients. This feat is only possible with full-body autopsies–an examinations of the body after a person has passed away.

The Last Gift Study

In response to this issue, Dr. David “Davey” Smith, an infectious disease physician and translational virologist at UC San Diego, embarked on a journey to find the hiding spots of dormant HIV in the body. This endeavor was inspired by one of Dr. Smith’s late patients who had regularly enrolled in various other HIV clinical trials until he became too ill to qualify for any more. Thus, the Last Gift Study was established as an ongoing collaboration of Dr. Smith, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), and the HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program in San Diego.²

The Last Gift Study consists of a clinical trial that enrolls and studies HIV+ patients without AIDS-related damage to their immune system, but with a separate terminal illness with a life prognosis of less than six months. The ultimate purpose of this study is to identify the hiding spots of HIV throughout the body to further prototype therapeutic interventions that may interrupt HIV migration from and around its hideouts in host reservoirs.

While participating in this study, patients elect to provide tissue and blood samples from regions of the body that do not require invasive surgeries. These include gut and rectal biopsies–extractions of small tissue samples–as well as blood, genital secretions, and cerebral-spinal fluid samples. However, very little is known about HIV reservoirs in less accessible locations such as the brain. Therefore, patients in this trial also consent to a full-body donation, and a rapid full-body autopsy is performed within six hours of the time of death to observe how HIV populates various tissues. As such, the samples collected before a patient’s death provide a baseline that can be compared against the post-death analysis of HIV replication. Most patients undergo ART during the study, though some have elected to cease treatment as they near the end of their prognosis. These incredibly personal decisions may provide researchers with additional insight on how HIV reservoirs change in those not undergoing ART.

End-of-life studies have existed in cancer research for quite some time, but the Last Gift Study is the first of its kind for HIV-related research. One large benefit of these end-of-life studies is the perceived risk-benefit ratio–patients with terminal illnesses may be more willing to endure frequent tissue sample collections as a means of giving back to their communities, an enormously selfless decision. In addition, owing to their terminal conditions, such patients may be willing to test experimental therapies, which is not possible in those with HIV viral loads well-controlled by ART.

HIV Hiding Places

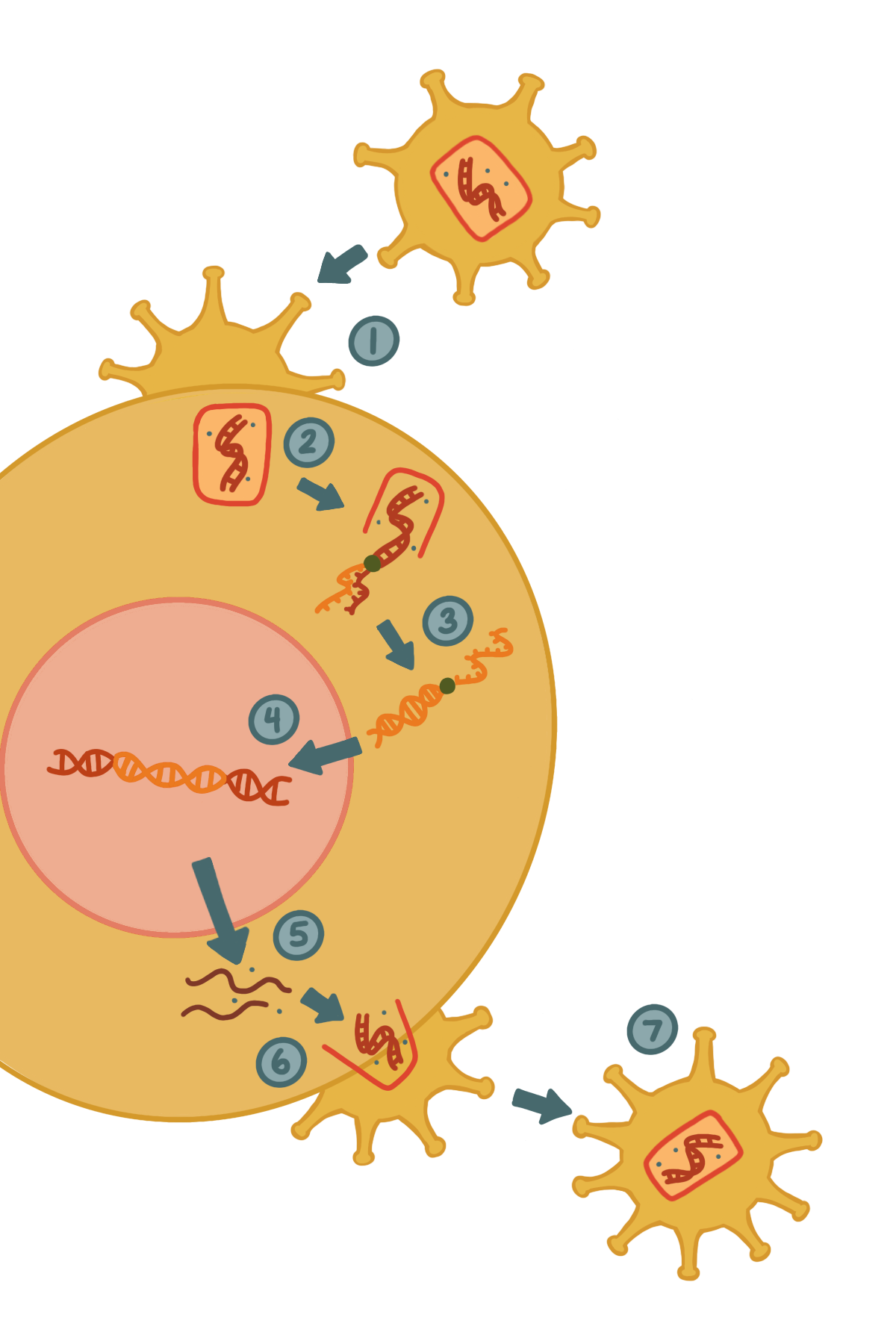

The cycle consists of HIV converting its double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) via reverse transcription, and integrating the dsDNA segment into the host genome.

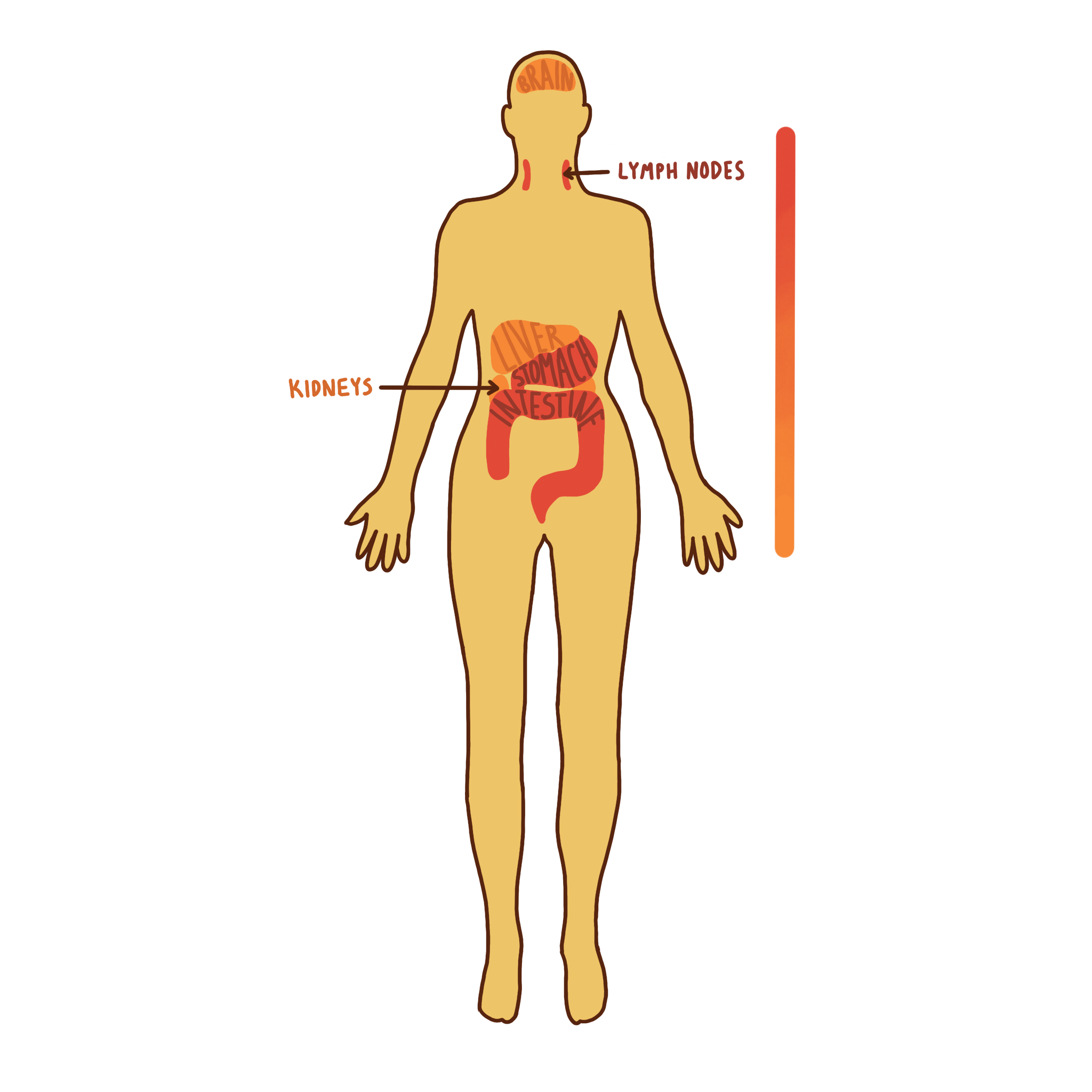

Dr. Smith’s team has determined valuable insights on HIV reservoirs which enable viral rebound after ART. Researchers measured the amount of HIV DNA specimens within the cells of a given blood sample and found that HIV was undetectable in the blood of patients taking ART.³ However, after death, HIV was detected in nearly all tissues. Because ART prevents HIV viral replication and ceases to function properly after a patient passes away, this result is not unexpected. More notably, researchers quantified higher HIV levels in the gut and lymph nodes than in kidney, brain, and liver tissues. This is expected, as macrophages and T-cells, or the immune cells which HIV infects, are more common in the gut and lymph nodes than in the brain.

However, it is important to note that while HIV does not populate the brain to the same extent as it populates other tissues, the brain still remains a major hub for HIV latency. Microglial cells, the brain’s resident macrophages, act as a brain HIV reservoir. Since ART and other therapeutic drugs often have difficulty crossing the blood-brain barrier, understanding how HIV utilizes the brain as a safe hiding place is crucial to clear HIV from the body entirely.

On another front, the Last Gift Study is careful to ensure that their research findings are not confounded by any comorbidities, or other medical conditions existing simultaneously within the same individual. For example, most HIV resides in the gut, but if an individual has colon or gastrointestinal cancer, investigations of the gut are better represented in other enrolled patients. Thus, this individual’s tissue may be more suited to study HIV in the brain. As a result, no one participant can contribute to the study of every tissue, but every patient can contribute something.

HIV Evolutionary Diversity

The Last Gift study also contributes to explorations of HIV evolutionary diversity. During infection, HIV converts its RNA genome into DNA via reverse transcription and integrates these DNA segments into host genomes with the help of virus-encoded cleavage enzymes. The integrated HIV DNA segment then remains in host chromosomes for months to years, lying undetected by the host’s immune system. Simultaneously, the cell continues to produce HIV virions that replicate and infect various cells across the body. During each instance of integration, the host attempts to mount antiviral defenses by introducing mutations into HIV DNA segments during reverse transcription. As a result, a diverse HIV group of variants is created across all of the HIV-infected cells in the body.

The Future of the Last Gift Study

Though the Last Gift Study is currently in its exploratory stage, Dr. Smith plans to implement various clinical trials that manipulate HIV to see if altering reservoirs across the body is possible. Eventually, Dr. Smith hopes to take the Last Gift Study further into testing possible therapeutics for HIV. In fact, CART-T cell therapy–a procedure in which immune cells are taken from patients, adapted to combat cancers, and subsequently reintroduced to the same patient–has been a main contender for HIV cure-related research.

So far, the Last Gift Study has established that HIV replicates and hides throughout the body and at different levels. Genomic sequence analyses permit researchers to track HIV as it moves between tissues. Additionally, HIV viral rebound occurs when patients cease ART, providing important insight as to how HIV might repopulate in the body. Though there is still much to be learned in the development of HIV cure-related therapies, with the advent of the Last Gift Study, humanity is many more steps ahead in this game of hide-and-seek. Perhaps one day, we can build a future where all of the hiding spots HIV takes advantage of are cleared from its threatening presence.

References

- Richman DD, Margolis DM, Delaney M, Greene WC, Hazuda D, Pomerantz RJ. 2009. The Challenge of Finding a Cure for HIV Infection. Science. 323(5919):1304—1307.

- Reardon S. 2018. Virus detectives test whole-body scans in search of HIV’s hiding places. Nature. 562(7728):472—473.

- Chaillon A, Gianella S, Dellicour S, Rawlings SA, Schlub TE, Oliveira MFD, Ignacio C, Porrachia M, Vrancken B, Smith DM. 2020. HIV persists throughout deep tissues with repopulation from multiple anatomical sources. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 130(4):1699—1712. https://www.jci.org/articles/view/13481.

- Wallet C, De Rovere M, Van Assche J, Daouad F, De Wit S, Gautier V, Mallon PWG, Marcello A, Van Lint C, Rohr O, et al. 2019. Microglial Cells: The Main HIV-1 Reservoir in the Brain. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology.

- Kirchhoff F. 2013. HIV Life Cycle: Overview. Encyclopedia of AIDS.:1—9.

Note From the Editors

Dr. Smith is looking for student volunteers to assist with this project. Anyone interested in getting involved in the project should email Dr. Smith at d13smith@health.ucsd.edu.

Written by Katelyn Nguyen

Katelyn is a Microbiology Major from Thurgood Marshall College. She will be graduating in 2022.