Some early mornings, a thick marine layer drifts over campus. If you are unfortunate enough to be caught in it, it would cover much of your vision and leave you waving your hands in front of you, unable to distinguish the distance between you and the blurred lamppost ahead. Everything in front of you seems distorted and imbalanced, and you feel like you’re wading through a dream. The fog envelopes your entire body, so heavy that your thoughts slow, your emotions become muted, and your hands blend with the rest of your surroundings–blurred, gray, and a source of confusion that leaves you guessing if they’re really a part of you. Now, imagine the fog follows you everywhere, even when you finally make it back to your room and greet your roommates cheerfully, even when you sit in your most difficult class trying to understand the new lecture. You are moving and interacting as usual, but you feel a disconnect between yourself and everything around you, between you and your sense of self. The fog makes the control panel in your mind lag, and your body has switched to autopilot, functioning outside of your own control. Everything around you has slowed, and you’re the only one who seems to have noticed.

Dissociative states, including depersonalization and derealization, describe a disconnection from reality. Like in occasional daydreaming, it can be normal and healthy, a response to everyday settings. In extreme cases, it may be described as a heavy “brain fog,” when surroundings or sense-of-self seem cloudy and detached. Since the 19th century, derealization and depersonalization, types of dissociative experiences, have been documented as severe dissociative symptoms that have been recorded in known literature. Depersonalization is described in the DSM-V as “experiences of unreality, detachment, being outside of one’s thoughts, feelings, sensations, body, or actions,” or a sense of detachment from the self. Derealization includes similar feelings of detachment towards external surroundings. Dissociation may serve as a coping mechanism in response to “feelings of helplessness, fear, or pain.” Approximately 3 out of every 4 people who undergo a traumatic experience will fall into a dissociative state that lasts from a few hours to weeks. Those suffering from sleep deprivation and high stress may also experience dissociation.

Those with depersonalization-derealization disorder (DPDR), a type of dissociative disorder, experience persistent or recurring states of derealization or depersonalization that may last up to months to years. Some experiencing derealization or depersonalization are still able to distinguish reality, alongside any distortions that might occur. In some cases, those suffering from such dissociative states may lose memory or awareness of their actions and surroundings.

Derealization and depersonalization may cause emotional numbness and unrealness. Likewise, it could cause a suppression of physical and autonomic, or involuntary, responses to negative emotions such as repulsion. A 2018 clinical trial measured electrodermal response, or skin conductance response (SCR), in patients with DPDR. These responses are due to an emotional output when one is encountered with an external or internal stimulus. It includes the automatic physiological reaction when skin becomes a more suitable temporary electricity-conductor, and it is usually measured by placing electrodes on areas of the body where there are ample sweat glands. The participants with DPDR showed they experienced prolonged delay in electrodermal responses to uncomfortable images, along with a shortened response delay to sudden noise. The trial showed that the intensity of the SCR was also much shorter than that of healthy participants in both stimulants. Researchers connected the increased length of SCR response in participants compared to the responses of control (healthy) participants to the inhibition of processing negative emotion in DPDR. Participants with DPDR showed a shorter SCR latency to the sudden noise, a non-specific stimulation, possibly due to increased alertness to their surroundings. While depersonalized participants may have an increased alertness, the trial suggests that they also experience selective inhibition of negative emotions, as shown by the drastic changes in latency and amplitude of SCR when participants encounter photos only with negative connotations. When encountered with photos of a positive or neutral connotation, SCR response delay in participants with DPDR was not drastically different from that of control (healthy) participants, implying that DPDR mainly affected response to negative emotions. The described emotional numbness and inhibited processing could be influenced by possible abnormalities in brain structure.

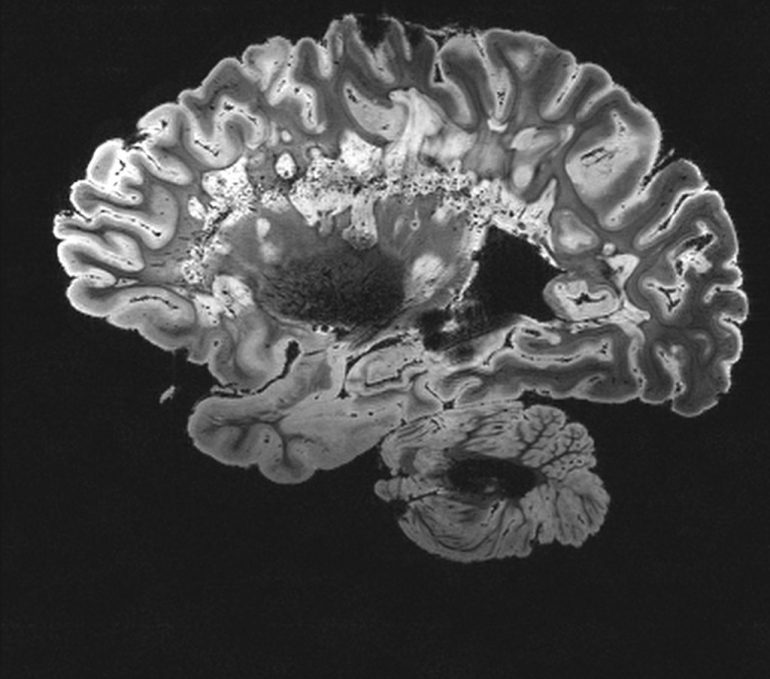

Very little is known about the neurological roots of dissociative experiences such as depersonalization and derealization. In an effort to better understand neural causes for dissociation, a 2015 study used voxel-based morphometry (VBM) technology to observe the brains’ gray matter in participants with depersonalization disorder. VBM uses MRIs, a technology using radio waves and a powerful magnet to scan images of the brain, to segment the brain into the different types of matter, such as gray matter and white matter. Researchers focused on gray-matter abnormalities in patients with DPDR. Gray matter contains many neurons and plays an integral role in neural functions such as emotion, movement, and memory. It is highly concentrated in the thalamus, which influences sensory awareness by aiding sensory input from other areas of the brain. Gray matter in the right caudate also plays an important role in the region’s regulation of emotional processing through input from corresponding areas of the brain.

Through scans produced by VBM in participants with DPDR, researchers noticed a decrease in brain matter in certain areas of the brain. Such decreases in gray matter correlated with the increase of symptom severity and decreased self-focus and positively correlated with a focus on awareness of surroundings. The thalamus, largely composed of gray matter, is one such area with observed decreases in gray matter of patients with depersonalization compared to in healthy controls. The right caudate also demonstrates a significant decrease in gray matter. Abnormalities of gray matter in both neural regions may contribute to the decreased sensory and emotional processing, as observed in people with DPDR. Furthermore, decreased volumes of gray matter were also observed in the occipital lobe, which controls depth and motion perception. This points to the 2D-like vision and difficulties gauging depths and distances which characterizes depersonalization and derealization. However, a study published in 2000 using PET scans showed that the occipital lobe actually demonstrated heightened activity in participants with depersonalization, as contrasted with healthy participants. This potential contradiction in research could be further analyzed.

On the other hand, increases in gray matter, such as in the superior frontal gyrus, correlates with decrease in mindfulness and increase in symptom severity and alexithymia, or difficulty identifying and detailing emotion. The superior frontal gyrus is the main center for attention and emotional control. These increases in gray matter of this region of the brain, compared to the controls, might contribute to difficulties in emotion regulation and self focus as reported by participants with DPDR. Gray matter concentrations were also increased in the brain’s right postcentral and superior temporal gyri. This seems counterintuitive, as both gyri are responsible for feeling bodily ownership and receiving information from sensory input. However, as seen in the PET scans at the separate study in 2000, when these regions are stimulated, it causes feelings of ungroundedness, which participants described as feeling “not present and floating away.” What remains unclear is whether the differences in gray matter are causal to the development of DPDR or if they are the result.

Dissociative disorders such as DPDR are under-researched and highly stigmatized psychiatric disorders. There are still many questions and ongoing theories about the neurological processes that contribute to such experiences. Along with the reductions and increases in gray matter in the brain, research also suggests that chemical imbalances in the brain might also contribute. In order to fully understand DPDR, more research must be conducted to explore its neurological causes, in order to progress the treatment for the persistent dissociative states.

References:

- https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm08#BABDICIH

- https://www.google.com/url?q=https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2020/09/researchers-pinpoint-brain-circuitry-underlying-dissociation.html%23:~:text%3DStanford%2520scientists%2520identified%2520brain%2520circuitry,from%2520their%2520bodies%2520and%2520reality.%26text%3DDissociation%2520is%2520a%2520phenomenon%2520in,their%2520bodies%2520and%2520from%2520reality&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1636988047767000&usg=AOvVaw34CjLKcfR_XunMlD-GeDCi

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/1025389031000138538?needAccess=true&

- https://www.media.mit.edu/galvactivator/faq.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4275327/pdf/jpn-40-19.pdf

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28479527/

- https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/mri

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553239/#:~:text=%5B6%5D%20The%20grey%20matter%20throughout,all%20aspects%20of%20human%20life.

- https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1782

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01614/full

- https://www.neurotransmitter.net/depersonalization.html

- https://depts.washington.edu/uwhatc/PDF/TF-%20CBT/pages/7%20Trauma%20Focused%20CBT/Dissociation-Information.pdf