Here’s a riddle for you–what do the sounds of successive tapping, whispering, hair brushing, massages, and Bob Ross’s voice all have in common?

If you have experienced ASMR, you might know that these are some common triggers for ASMR.

So, what is ASMR?

To begin, ASMR stands for “autonomous sensory meridian response.” ASMR is a fairly recent term, coined in 2010 by Jennifer Allen, that describes the pleasant tingling sensations that some people feel during certain experiences. These may include listening to people talk slowly, having a story read to them, or when someone traced a finger on their skin. These sensations often start at the back of the scalp, travel down the spine, and then sometimes spread to the shoulders, lower back, and limbs. At the time, there was no official name to collectively refer to these sensations, and they were dismissed as nothing more than an unusual obsession.

As a result, Allen took it upon herself to generate a name that would allow people to share their common experiences, without the fear of coming across as abnormal. She ultimately settled with “autonomous sensory meridian response.” According to Allen, “autonomous” describes the independent nature of certain triggers that induce the tingles without external control. “Sensory” signifies the involvement of the senses, and “meridian” refers to the highest point, or climax, of these sensations. Lastly, “response” communicates that this experience is a reaction to a specific set of stimuli, rather than an ongoing state. When the term was finalized, it made its way through the internet and ultimately caught the attention of the scientific community.

The first scientific investigation of ASMR was a 2015 study that surveyed 475 individuals who claimed to experience the phenomenon. This study laid the groundwork for future investigations by identifying the triggers that typically induce the sensations and by exploring reasons why people watch ASMR videos. Whispering, personal attention, slow movements, and crisp sounds such as fingernail tapping were found to be triggers for more than half of the study participants. Furthermore, this study found that the most common ASMR sensations included tingles, relaxation, sleepiness, and feelings of comfort. When asked for the purpose of engaging with ASMR content, almost all of the participants reported using ASMR as a means to relax. Other study participants looked to ASMR for assistance with falling asleep and coping with stress.

When looking at the triggers and the associated sensations as a whole, some theorize that ASMR may be simulating affiliative behavior due to the neurohormones that are suspected of being involved. Affiliative behavior, or interactions related to social bonding, involves an exchange of caring behavior such as grooming or smiling and typically occurs between family members, friends, and couples. Triggers such as whispering and personal attention could be interpreted as affiliative behavior due to their intimate nature. Other sounds and triggers, such as tapping, scribbling, or turning pages, may be indirectly affiliative because they are the sounds of loved ones being near and occupied with other activities. The neurohormones that are responsible for affiliative behavior are dopamine, oxytocin, and endorphins. These neurohormones are known to produce feelings of comfort, sleepiness, and relaxation, the same feelings that are often reported in ASMR sensations. Moreover, positive social bonding experiences are linked to increased oxytocin levels and reduced stress hormone levels. Therefore, the activity of these neurohormones provides a potential explanation for why ASMR appears to help relax individuals.

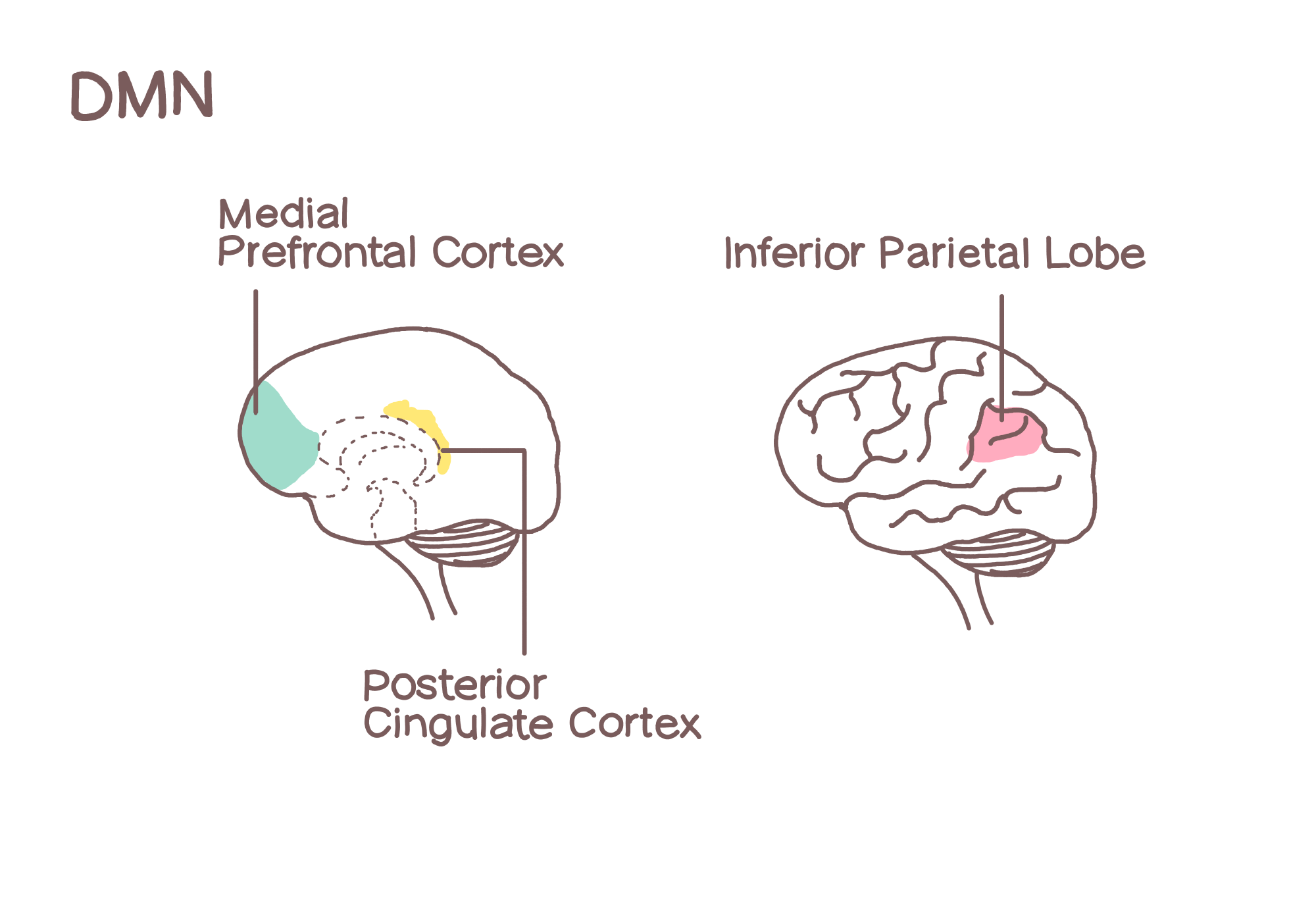

This then raises the question of why some individuals experience ASMR while others do not. Differences in ASMR sensitivity may be attributed to ASMR-sensitive individuals possessing neurobiological wiring that is distinct from their ASMR-insensitive counterparts. A 2019 study observed several resting state networks of the brain and found that individuals who experienced ASMR had less distinct and more blended resting state networks than those who did not experience ASMR. A “brain network” simply refers to a group of brain regions that demonstrate correlated activity, or functional connectivity, when performing specific functions. Thus, resting state networks are brain networks that operate when a person is unoccupied and not engaged with a task or stimulus. In the study, one of the observed networks during resting state is the default mode network (DMN), which is associated with mind wandering, episodic memory, and introspection, and typically consists of the medial prefrontal cortex, inferior parietal lobule, and posterior cingulate cortex.

During resting state, ASMR-sensitive individuals not only exhibited reduced functional connectivity in the DMN, but the DMN of ASMR-sensitive individuals was also found to work with other brain regions that are not a part of this network. This collaboration between the DMN and other brain regions suggests that the brain networks in ASMR-sensitive individuals are more blended than the brain networks of people who do not experience ASMR. In another example, activity in the sensorimotor network (SMN) correlated with activity in the area containing the orbital gyrus, the region of the brain associated with rewards, in individuals who experience ASMR. The connection between the SMN and reward-related regions may help explain why ASMR tingles feel satisfying and rewarding to those who experience them. These results indicate how a blending of brain networks may give rise to multimodal experiences like ASMR.

Despite the seemingly mysterious nature of ASMR, the relaxing effects of its visual and auditory triggers have therapeutic applications, including temporarily alleviating symptoms of depression, anxiety, and perhaps even autism spectrum disorder. ASMR is still not well understood, but scientists have envisioned treatments that can be executed in tandem with health professionals. However, before the therapeutic advances, much more research is warranted to both understand the physiological mechanisms of ASMR and to devise a strategy that will take advantage of its benefits.

Sources

- https://www.steadyhealth.com/topics/weird-sensation-feels-good

- https://asmruniversity.com/history-of-asmr/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/04/magazine/how-asmr-videos-became-a-sensation-youtube.html

- https://peerj.com/articles/851/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6209833/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6648236/

- https://juniperpublishers.com/pbsij/pdf/PBSIJ.MS.ID.555859.pdf

Illustrations drawn by Lu Yue Wang and Svetlana McElwain