Today, I want to tell you a little bit about a movie that I watched recently. It’s a well known Peruvian film entitled La Teta Asustada, which translates to “The Milk of Sorrow”. The premise of this movie is based on an old Andean folktale that emerged around the 80s –a time of great violence in Peru. Thousands of women across the country were raped, and families slaughtered. For those who survived, the trauma was forever burned into their minds; the story goes that traumatized mothers would pass on their paralyzing fear to their offspring through their breast milk. While this is only a folktale, it sets the stage for future discoveries centered around the idea that our human experiences are more heritable than we ever imagined. Our epigenome, the way our genetic material is organized and packaged, has been shaped by our experiences and those of our ancestors. In fact, one recent study showed that offspring of Holocaust survivors exhibited the same “trauma-related” altered methylation patterns as their parents, meaning that unfortunately this Peruvian folktale has a great deal of truth to it (2). While the predictive power of Peruvian folktales is nothing short of amazing, it leaves me wondering how this is all possible.

To address how experiences can even be heritable, we have got to back up a bit and address something we’re all a bit addicted to. Specifically, I need to confront your addiction. The one you know is bad for you. The addiction whose side effects can be debilitating, but you so desperately need it as a coping mechanism. It’s one of the most prevalent addictions of the 21st century: STRESS. That wonderful sensation that has grown to become your best friend during the course of your college career. You’ve tried to get rid of it countless times, but without success. And now, you’ve come to this very article to seek help— or at least understand the ramifications of this dependence. Now, I’m not here to tell you to “meditate every morning” or “step away from the screen”, because for many of us, these objectives are not feasible (I’m looking at the no-screens-two-hours-before-bed rule). But if we understand stress from a biopsychosocial perspective, then we may be able to manage it better.

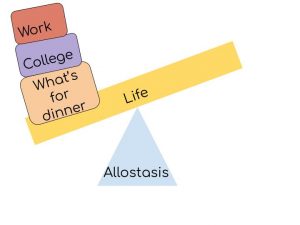

The first step to recovering from our “stress addiction” hinges on acknowledging what stress entails. Contrary to popular belief, stress does not have to be detrimental. In response to the stressors that plague our daily lives, our bodies have come up with a combat weapon known as allostasis. Allostasis refers to the physiological response we have to short term stress that helps us build resilience to environmental threats (1). Some examples of allostasis that you’ve probably experienced include increased heart rate when you remember you have a paper due tomorrow, or elevated blood pressure when you finally start that exercise routine. In short, it helps regulate our body to communicate with the various obstacles we face throughout the day, whether it be noise, hunger, temperature changes, or even crowds. A good way to think of allostasis is like the fulcrum to a seesaw; it moves to keep you balanced. However, allostasis is not a panacea for all stress. In fact, chronic stressors cause allostasis to malfunction and go into allostatic overload which can cause epigenetic changes that may unintentionally be propagated into the next generation (1).This means that stressors have the potential to impact future generations that haven’t even had exposure to the original stimuli. This makes sense–if we overload the allostatic seesaw, then no matter how much the fulcrum is moved, balance simply won’t be achieved.

The word stress has become quite overused in our society as we have grown to associate the most minor inconveniences with supposed “stress”. Does ordering soy milk instead of almond milk stress you out that much? I didn’t think so. To distinguish between actual stress and colloquial hyperbole we need to remember the wise words of Dr. Hans Seyle: “ It’s not stress that kills us, it’s our reaction to it”. Major stressors that have been linked to reactions include child abuse, neglect, war, famine, violence, lack of care/support, and a low socio-economic status (1). That isn’t to say other stressors don’t stimulate the same response, but those listed most commonly elicit a bodily response.

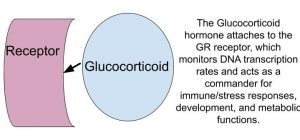

What is this “response” and what significance does it have? It’s not as simple as perspiration or elevated heart rate. As mentioned previously, scientists have researched stress and found that it has the ability to induce changes to methylation, histones, mRNA, and glucocorticoid signaling. What is glucocorticoid signaling? Well, for one, it is a mouthful to say, but it is also an endocrine process that stems from the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis’s release of the glucocorticoid hormone (1).

Yes, that entire sentence was English; but don’t worry, I’ll explain using my favorite method—the analogy.

The endocrine system is all about sending messages in hopes that the net effect is regulatory—kind of like the US Postal Service. One of the important routes of the endocrine postman is delivering messages between his most important clients: the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal gland. Although they each have their own functions, when used together they achieve a superadditivity that makes for a highly efficient stress response. This highly efficient process results in the delivery of an integral package: the Glucocorticoid.

Let’s take a closer look:

Why does this matter? Epigenome changes are associated with a higher risk for some of the leading causes of death (e.g. heart disease, depression, impaired ovarian function, etc), but that’s not all. Think about a time when you went through a major life change. You were probably more sensitive and vulnerable in some respects. On a more microscopic level, our bodies mimic this same phenomenon. When gene expression is altered, bodily system responses are prone to dysfunction (the endocrine system for instance may be more reactive which can lead to mood swings and frequent cravings).

Before you begin to contemplate your decision to pay six-figures to subject yourself to gene changing stress everyday for 4 years, you should know that studies have shown that we are more sensitive to these changes during early life (pre- and post-natal care) and late age (1). Of course, this often depends on the type and length of stressor, so you aren’t completely immune to these changes in adolescence or adulthood. In fact, after early life the epigenome tends to become more and more sensitive to changes in certain respects because we acquire more cumulative stress.This means that chronic stressors in adulthood and adolescence can accelerate epigenetic aging and put us at a greater risk for future depression or anxiety (1). And although little research has been conducted (mostly in mice), there is a slight indication different stressors can interact in different ways and accumulate to remodel the genome long after a stimulus is gone (1).

Stressed yet? Well, all hope isn’t lost just yet. Sometimes biology alone isn’t enough to resolve the “stress epidemic”. Social science perspectives are a tremendous asset that allow us to look at systemic issues in order to resolve stress. Thus, we are best served by examining both areas in conjunction when we think about limiting the control that stress can have over gene expression.

If we look at other mammals, their social structure parallels ours in several ways. The dominant (at the head of the pack) members have access to resources that are limited for subordinate (lower status) members.This includes territory, food, mating, and protection, which causes subordinate members to have higher baseline levels of stress (2).This makes sense, as after all, we are bound to be more stressed if we are at a disadvantage for surviving.

In monkeys, fish, and baboons rank-related stress has been associated with transcription and hormonal changes that are subsequently associated with disease risk (2). Want a fun fact for the dinner table? Higher ranked Savanna baboons have been shown to have less behavioral disorders and faster wound-healing than their subordinates (2).

Indeed, as humans, we are aware of social status as early as the age of two! Our social organization facilitates a system of stress that often falls heavily on the shoulders of those with lower socioeconomic status which leads to epigenetic changes that can create psychological issues (2). For instance, those who experience early childhood abuse may have more amygdala (fear factor) reactivity in adolescence which puts them on track for adult-onset depression (2).

So there is a clear systemic issue, and while a radical overhaul is not the most practical or logical solution there are intervention-based actions that the public health community can employ to reduce the impacts of stress. Low maternal stress and violence, increased parental care and protection (especially throughout adolescence), parental support, and general avoidance of trauma, poverty, famine, and war (which is of course easier said than done) can provide an infrastructure for people to experience stress in a healthy manner as opposed to having it serve as a constant burden (2).

As for us students, I suggest you should turn-off all screens two hours before bed. Perhaps even consider embarking on a fancy meditation retreat this summer. I’m joking of course, but, hopefully, knowing the implications of stress can help you consider implementing stress-management techniques into your life. Try out different things and find what works and what is sustainable for you, whether it’s something as small as lighting candles or taking up a new hobby like bird-watching. Now, maybe you should get back to that paper due later?

Sources:

- https://www.nature.com/articles/mp201735

- https://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/full/10.2217/epi-2016-007