MADELEINE YU | ONLINE REPORTER | SQ ONLINE 17-18

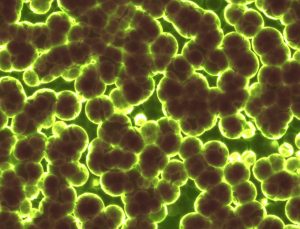

They surround us by the billions in every nook and cranny imaginable, even hitching a ride with us throughout our daily routines. All the while, we are oblivious to their presence.

Microbes.

Despite their ubiquity in our world, little is known about these microorganisms. But, some researchers here at UC San Diego are starting to make headway in chipping away at the microbe mystery.

Researchers at the UC San Diego School of Medicine and Center for Microbiome Innovation have collaborated to develop technologies that detect the presence of microbes and chemicals in a manmade environment. For the first time, this detection extends to the identification of the particular individuals involved, even going as far as detailing who touched what in the space.

Cliff Kapono, a doctoral candidate under Professor Pieter C. Dorrestein at the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences within the UC San Diego School of Medicine played an instrumental role in the process of data collection. Kapono and a large team of researchers were tasked with creating an inventory of the bacteria and chemicals in an office space, and to swab the individuals who interacted with the space.

“[The team] swabbed a bunch of areas–the hands, face, legs, back, and chest, for instance–and then we introduced the samples to mass spectrometry and genome sequencing,” states Kapono. Next, the identified samples were overlaid onto a 3D map of the office space, revealing the locations of the microbes taken from individuals that were now also in the environment.

Nocardiaceae (Fig. 1i), a bacteria commonly found in soil, was noticeably prevalent on the office floor. Another environmental bacterium, Acinetobacter guillouiae (Fig. 1j), which is present in water, soil, and feces, was also in the room–particularly on the hands and face of one of the volunteers. The marine Cyanobacteria from the genus Synechococcus (Fig. 1i) was found on another volunteer’s body. A third volunteer had a high abundance of Actinomycetales (Fig. 1m) on their body, phone, and computer. A bacteria from the genus Staphylococcus (Fig. 1n) was also found on one volunteer, while Veillonella parvula (Fig. 1o), a microbe associated with the human oral microbiome, was found on the arms and chest of another.

While previous studies in the Dorrestein lab examined the microbes left on surfaces of phone screens and on the stains of carpets as an indication of an individual’s personal lifestyle in the past, this study went one step further to identify the individuals that inhabited the space as well as which items they touched by comparing the microbes and chemicals present on their bodies to those found in the office space. As Kapono puts it, the bacteria became a kind of a “molecular signature”.

“It’s the next generation of fingerprints,” says Kapono. Through these microbial traces of human activity, he believes we can understand the small-scale interactions between nature and man. He may not be too far off either; according to the study, the sampled microbes in the office correlated to the correct individual with about 76 percent accuracy. The study has the obvious potential to apply to forensics. However, to Kapono, the acquisition of information to arrive at a bigger picture is most important.

“We’re not trying to put people in jail,” Kapono explains. “Sometimes there isn’t enough data in forensics and there needs to be another supplementary tool.”

In addition, Kapono hopes that this study will bring about an examination of workplace environments.

“Facebook, Google–companies that keep employees around for extended periods of time–can use this method and can show how the chemical and biological environment affects the workplace health, however positive or negative.”

Kapono’s childhood has influenced his particular intent on revealing the world of microbes through research. Born on The Big Island of Hawaii, Kapono grew up in a community that had strong ties to nature.

“We belong to nature,” Kapono echoes, a lesson long since ingrained in him. “I have an abundance of indigenous knowledge that I want to communicate to those who did not grow up with the same background, and science is a very powerful way to share with a global audience the connection to nature.”

A member of the professional surfing community, Kapono has a long held fascination with the ocean. He initially began doing research with coral reefs and the molecular interactions between them. Since then, Kapono has expanded his projects to include molecular interactions between humans and the environment, filmmaking for indigenous activism, ocean conservation, global food security, and virtual reality.

“Not everyone can go to certain places,” says Kapono. “Things like VR and filmmaking allow for just that. People want to know: ‘where do I fit on this planet?’”

While the office study mainly looked at the individual’s influence on the environment, Kapono also is interested in looking at the environment’s impact on the individual. The project ended up becoming a kind of launching point from which Kapono’s Surfer Biome Project began. With the support of the UC San Diego Global Health Institute, Kapono created this project with the intent of exploring the existing molecular signature–by way of the chemicals and bacteria–that connects humankind to the ocean.

“By understanding the relationship with the environment, we can improve global health,” states Kapono.

He hopes to connect with the prime participants for his ocean-focused study: surfers. “I am very fortunate to not only like to surf, but to also be a part of a community that surfs.”

Through this unique opportunity, Kapono plans to not only benefit from his involvement in a surfing community, but to also give back.

“I want to empower these communities; they are a facility through which to power social change. Because people in this community are fascinated by the sea already, it’s a nice way to communicate science.”

Kapono’s goal of educating the community has already inspired collaborations with The Polynesian Voyaging Society, the National Geographic Society, Sustainable Coastlines Hawaii and The Biomimicry Institute. He is set to obtain his PhD in Chemistry in May from UC San Diego, but his work won’t stop there. Awarded an AAAS Mass Media Fellowship, Kapono will go on to write science articles for the Los Angeles Times, and eventually return home to Hawaii, where he will work on more grant applications so that his research with surfing can begin.

Research with microbes is vast, intriguing, and perhaps most importantly, expanding. This interest is not only prevalent within the lab setting, but in the popular media also–perhaps due in part to Kapono’s advocacy for everyone to have access to the sciences. Already, media outlets such as The New York Times, NBC, CBS, Surfer Magazine, and Hawaii Business Magazine have featured Kapono’s work. Who knows what further discoveries there will be in the near future when the answers lie–literally–at our fingertips. Until then, Kapono’s work serves well to remind us of how connected we are to our workspaces, nature, and each other.

[hr gap=””]

Cliff Kapono would like to acknowledge the UC San Diego Global Health Institute, Professor Dorrestein, the American Gut Project, and the Sloan Foundation for making his research possible.

Resources

- http://www.cliffkapono.com/

- https://pharmacy.ucsd.edu/faculty/bios/dorrestein.shtml

- https://health.ucsd.edu/news/releases/Pages/2017-10-19-microbial-anatomy-of-an-organ.aspx

- http://dorresteinlab.ucsd.edu/Dorrestein_Lab/Publications.html

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-21541-4

- http://www.cliffkapono.com/new-page/

- http://globalhealth.ucsd.edu/Pages/default.aspx

- https://www.aaas.org/page/about-1

- https://pixabay.com/en/bacteria-germs-microbes-medical-1959386/

- https://pixabay.com/en/bacteria-pathogen-infection-germs-1744856/