BY LAUREN BRUMAGE | SQ ONLINE WRITER | SQ ONLINE (2017-18)

Imagine the following scenario: you are in a crowded lecture hall, hunched over a tiny desk and staring blankly at an exam. Your heart races and you feel a gnawing headache take hold as you struggle to gather your thoughts to focus on the task in front of you. Fear of failure grips you and clouds your mind.

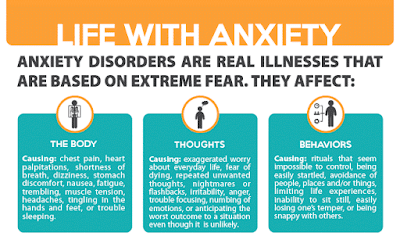

![]() These sensations, experienced by many students at some point in their academic career, are all common symptoms of anxiety. For many people, anxiety is fleeting and associated merely with high-pressure situations such as an exam or a presentation. However, for others anxiety is a chronic and sometimes debilitating condition. When a person experiences anxiety almost ceaselessly for an extended period of time, they are said to have an anxiety disorder.

These sensations, experienced by many students at some point in their academic career, are all common symptoms of anxiety. For many people, anxiety is fleeting and associated merely with high-pressure situations such as an exam or a presentation. However, for others anxiety is a chronic and sometimes debilitating condition. When a person experiences anxiety almost ceaselessly for an extended period of time, they are said to have an anxiety disorder.

“Anxiety disorder” is an umbrella term for a number of closely related, yet distinct, conditions. General anxiety disorder (GAD) patients experience general anxiety regarding everyday life for which they often cannot pinpoint a rational cause [1]. On the other hand, social anxiety disorder (SAD) patients have a more specific anxiety related to fear of being judged that leads to difficulties in socializing with others [1]. According to the National Institutes of Health, the third primary type of anxiety disorder is panic disorder (PD), a condition characterized by a proclivity for sudden and intense waves of fear called panic attacks [1]. Other conditions, such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and specific phobias are closely related to, and may occur in combination with, anxiety disorders [2].

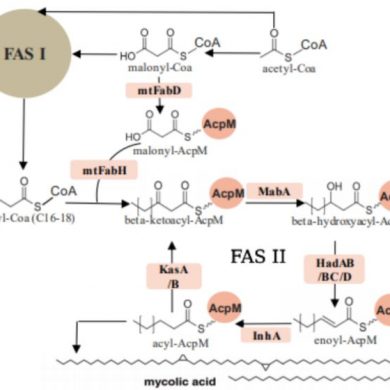

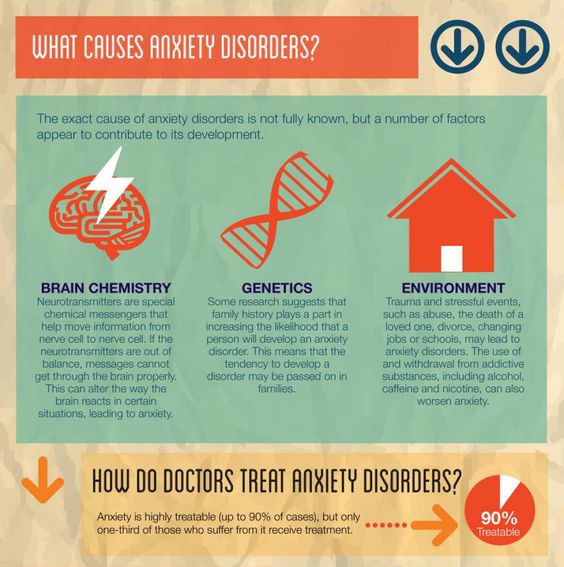

What actually causes anxiety disorders? Researchers do not yet have a complete answer to this question. In some cases, anxiety disorders appear to be hereditary, but current data suggest that traumatic or distressing life experiences can also induce anxiety disorders [1,2]. Certain medications or substances (such as caffeine) can enhance anxiety, although it is unclear whether any of these can actually cause an anxiety disorder [2].

Recent research has shed light on a possible biological mechanism through which anxiety is modulated. A team of neuroscientists and psychiatrists from universities around the country recently published findings in the journal Neuron that describe so-called “anxiety neurons” in mice. Stimulation of the neurons in one area of the hippocampus activated a neuronal circuit that coincided with avoidance and anxiety behaviors in mice, leading the researchers to suggest that the neurons stimulated exert an influence on anxiety [3]. These findings are supported by previous data indicating that the hippocampus might be involved in mood and anxiety disorders [3]. While this study was performed in mice, it is quite possible that the results could apply to humans as well since mice have been successfully used to model other human disorders. If anxiety neurons are indeed present in humans, they could represent a novel and more specific target for future anti-anxiety medications [3].

Current anxiety treatment is imperfect. The aforementioned anxiety disorders are not mutually exclusive; thus, an individual suffering from SAD may also have PD. This factor, as well as the possibility of other mental illnesses such as depression co-occurring with anxiety, complicates treatment. Each patient has a distinct combination of symptoms and unique life experiences, meaning that a “one size fits all” approach to treatment is folly. A medication that relieves one patient’s symptoms may exacerbate the symptoms of another patient.

Many medications exist, and for some patients they are effective with few side effects. Benzodiazepines and beta blockers work fairly well for short-term symptom relief, but if used for long-term control of anxiety, addiction and mitigated efficacy can occur [4]. Buspirone is used in patients who need a long-term anxiety control medication [4]. Antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), are often used to treat patients with SAD [4]. All of the above medications have the potential for side effects including but not limited to nausea, headaches, irritability, and (ironically) anxiety [4]. Not all patients experience side effects, and some experience only minor side effects. Regardless of the side effects, the best outcome that can be expected from medication is the masking of symptoms. No anti-anxiety medication currently on the market cures anxiety disorders.

To truly confront or cure an anxiety disorder, it is critical to find the cause. Psychotherapy, or talking with a psychologist, can help achieve this goal. Psychologists can help patients get to the root of their anxiety and, through cognitive behavioral therapy, teach them techniques to manage and inhibit their anxiety [1]. For patients with SAD, this may involve the patient learning strategies for navigating social situations [1]. Medication may be a useful aid in the process, similar to using training wheels while learning how to ride a bike. Once an individual feels confident in their ability to confront and control their anxiety, they can taper off their medication.

Even though anxiety disorders are the most prevalent form of mental illness in United States, impacting as many as 40 million adults, only an estimated 36.9% of those suffering from anxiety actually seek treatment [5]. Perhaps the primary factor contributing to failure to seek help is the stigmatization of mental illnesses, including anxiety, in the United States. Persons suffering from a mental illness are often stereotyped as damaged, weak, failed individuals, or as potentially threatening to society [6]. These stereotypes are reflected in lack of social support for, and sometimes outright ostracization of, individuals who confess their struggle with anxiety disorders or other mental illnesses. Furthermore, health insurance may not adequately cover mental health care making economic accessibility a barrier to treatment [6].

Anxiety is a relatively common issue here at UC San Diego as well as at many other college campuses. I’ve struggled with anxiety myself over the years and, judging by the multitude of teary and stressed conversations that I have overheard while strolling down Library Walk, so have many other students. What can be done about anxiety disorders? Individuals who do not have an anxiety disorder should be supportive and open-minded to people who do have an anxiety disorder. People suffering from anxiety disorders do not choose to suffer from those disorders and they may simply be too afraid of social (or professional) backlash to seek help. Those who suffer from an anxiety disorder should remember that they are not alone as anxiety disorders are much more common than people think! They should not be afraid to seek treatment as anxiety is not something to be ashamed of. Having an anxiety disorder does not mean that a person is broken, or dangerous, or a failure at life or any other such nonsense. There are always people who can help, such as the professionals at Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) here at UC San Diego. Getting treatment, or at the very least building a support network of family and friends, can make life much more enjoyable in the long term.

Additional Resources

- Project Implicit from Harvard – implicit bias tests regarding mental health topics

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America – useful resources on how to manage and overcome these mental illnesses

- UC San Diego Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS)

[hr gap=”0″]

Sources

- https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders/index.shtml

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anxiety/symptoms-causes/syc-20350961

- http://www.cell.com/neuron/pdf/S0896-6273(18)30019-9.pdf

- https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/mental-health-medications/index.shtml

- https://adaa.org/about-adaa/press-room/facts-statistics#

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/mental-illness/in-depth/mental-health/art-20046477