MADELEINE YU | ONLINE REPORTER | SQ ONLINE 17-18

Nearly everyone knows someone affected by Alzheimer’s disease; it has become a leading medical issue and is often at the forefront of pharmaceutical research. Every year, more and more drugs are introduced for testing, but despite this abundance, not one has managed to succeed in finding a cure. Just two years ago, pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly tested a promising drug called solanezumab that appeared to slow down the progression of Alzheimer’s. However, the drug subsequently failed in a large clinical trial disappointing many who had hoped to finally find a solution to the insidious disease.

Alzheimer’s is characterized as a form of progressive mental deterioration which starts with the loss of ability to form new memories. The disease can later impact the retention of old ones, detract from everyday functionality, and severely alter behavior and personality. With more than 5 million Americans currently diagnosed around the average age of 65, Alzheimer’s is currently the 6th leading cause of death in the United States, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. At the rate at which diagnoses have increased, the number of affected patients is projected to rise to as high as 16 million by the year 2050 in America alone. With so much on the line, Alzheimer’s research can be difficult to conduct when funding is competitive and the pressure to succeed is high.

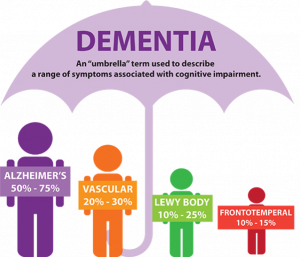

At this point in time, there is no test that can accurately diagnose someone who may have Alzheimer’s. At best, a combination of medical history, cognitive tests, and doctor exams can infer the possibility of dementia, but there are also a host of other physiological conditions–depression, excessive alcoholism, and thyroid problems, for instance–that can produce symptoms characteristic of the disease. Dementia itself encompasses a wide umbrella of subtypes that all demonstrate cognitive impairment in varying ways, but does not necessarily indicate the development of Alzheimer’s.

The identification of Alzheimer’s can only be made certain post-mortem when the physical brain is examined. Only then can doctors visually confirm the disease’s pattern of degeneration, which spreads from the medial temporal lobes–affecting the hippocampus implicated in memory consolidation–to the outer cortex–attacking more stable, older memories–and lastly to the frontal lobe, which is involved in decision making and inhibition.

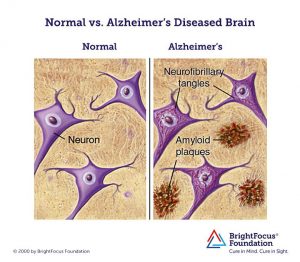

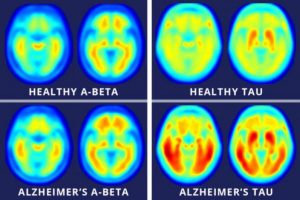

Researchers have used neuroimaging to look for ways to actively identify the onset of Alzheimer’s and have settled upon two main signifiers: the presence of amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles located in brain areas associated with memory and cognitive function.

While naturally-produced amyloid-beta proteins are typically degraded and flushed out of the brain, those with Alzheimer’s experience an accumulation of the protein which build-up into insoluble plaques. Meanwhile, neurofibrillary tangles are composed of a protein, tau, an essential component of nerve cells that helps with the transport of nutrients and signals from one end of a neuron to the other. In Alzheimer’s, tau functions abnormally, causing the structures of neurons to collapse and become tangled. Despite these landmark indications of the disease, the exact cause of Alzheimer’s remains unknown and even the knowing whether or not one is at risk for the disease is difficult and can be extremely expensive.

There is evidence coming to light about the biological necessities for amyloid-beta protein. A new study by the Massachusetts General Hospital has found that expression of amyloid-beta combated potentially lethal pathogens in mice, roundworms, and cultured human brain cells. Another study published in the Journal of Neuroscience demonstrates that the protein is necessary for long-term potentiation (i.e., learning) and memory. While these findings are few, their sheer presence should be cause for contemplation. Many pharmaceutical companies aim to eradicate amyloid-beta completely due to its association with Alzheimer’s, and this can be harmful.

Last year, at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in London, results of a four-year study showed that a significant number of those currently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s may not actually have the disease. Because getting a PET scan of the brain costs around $6,700 on average, most patients opt for a diagnosis based off the symptoms alone. As a result, those with other forms of dementia aren’t getting the right treatment that could mitigate, or even cure, their symptoms.

As of February this year, there is new research out of a collaboration between research universities and centers from Japan and Australia that proposes a new method of Alzheimer’s diagnosis–through blood samples. Perhaps most promising is the accuracy of the test: an impressive 90% of the 232 participants who underwent trials were correctly diagnosed, either newly discovered or validated with the disease. However with the continuous cycle of promising treatments failing in clinical trials, and the intensity of media surrounding Alzheimer’s research, it is difficult to know when the reported results are trustworthy and when readers should take it with a grain (or two) of salt.

These conflicting perspectives on the best way to diagnose and treat Alzheimer’s show that it is a very complex disease that is incredibly scary in its prevalence. Since so many are affected, the need for a solution continues to persist. However, while so many are conducting research under the time crunch of federal grant deadlines, some major setbacks are made when results are rushed. Like in the case of Eli Lilly’s trials with solanezumab, though the drug failed previously in two large clinical trials, the company still reported a significant effect in a subset of patients. This allowed Eli Lilly to receive further funding and to continue onto the next trial.

In further pharmaceutical news, Biogen Inc presented their best option, aducanumab, shortly after solanezumab’s failure. While Eli Lilly’s drug attacked free-flowing amyloid-beta proteins, Biogen’s aducanumab targets the proteins that have already accumulated into plaques. Many hope that this will be the difference in finally finding the cure for Alzheimer’s. Results for the drug’s most recent trial are set for release in 2019.

Though it is good for Alzheimer’s to receive so much attention from the media and the public, too much pressure to find solutions can negate any progress towards the correct path if it is seen as too slow and costly. So, will the new blood test measure be an advancement in Alzheimer’s diagnosis? Will Biogen’s new drug be the cure we’re looking for? It remains to be seen.

[hr gap=””]

Resources

- https://www.nature.com/articles/nature25456.epdf?referrer_access_token=c8PIrOptZE44YmSG4d_-zdRgN0jAjWel9jnR3ZoTv0MbB_79egWQegc3WHcWU_RBzvrBYyGkDYVMgN6lIl73k22Tr_eG7fRflsP0VL8nUV0FNjz_6b94KP86II0MkHitHPPNLbN2N0lXIuSnTytP2aEQGr1L4BrZm5FAnw4QUtC3PdEiRje92B6os00qOJEh10kkpJjbnDXApNYD9716Pxlb3_dCEhZHeYLJUCAkyzsvcZj3C59j3TEtG-MQJqyx&tracking_referrer=www.cnn.com

- https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/how-alzheimers-disease-diagnosed

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1552526017338530

- http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/obr.12629/full

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006322317322539

- https://www.alz.org/facts/

- https://www.bostonglobe.com/business/2017/09/26/biogen-best-hope-alzheimer/iYq5Yiz7kTRmbWQZeO8TEK/story.html

- https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/23/health/eli-lillys-experimental-alzheimers-drug-failed-in-large-trial.html

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/brain-scans-show-many-alzheimers-patients-may-not-actually-have-the-disease/2017/07/18/52013620-6bf2-11e7-9c15-177740635e83_story.html?utm_term=.c8308ff8ba08

- https://www.alz.org/dementia/types-of-dementia.asp

- https://www.brightfocus.org/alzheimers/infographic/amyloid-plaques-and-neurofibrillary-tangles

- http://www.dfwsheridan.org/types-dementia

- http://www.newsweek.com/brain-scans-alzheimers-disease-tau-proteins-amyloids-458733