MADELEINE YU | ONLINE REPORTER | SQ ONLINE 17-18

It is strange to think that our sense of body is not confined to the limits of our physical being; yet, this has been proven true in a vast number of scientific studies. The body can extend beyond its physical limitations; for instance, a study in 1996 demonstrated that neurons in the brains of monkeys respond to touch both on the hand and on handheld tools, such as a rake, used to reach distant objects. This indicates that the brain stretched its representation of the hand to include the rake. Studies have gone further to examine the phenomenon with rubber hands, the cars we drive, and, perhaps more importantly, with mirrors.

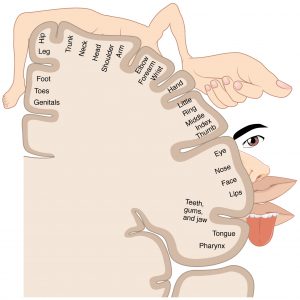

Within the brain, our entire body is mapped out in the somatosensory cortex, an area in the Parietal lobe that stretches like a band over the top of the brain from right to left. Neurons within this area receive signals directly from their respective body part. There is a natural interdependence between the brain and the body where the brain receives sensory signals sent by each body part, such as pain, temperature change, and location with respect to the rest of the body. The brain then sends the body signals to move or act in response to the external stimuli. However, what happens when this connection is severed?

For the rare few who have lost a part of their body, either surgically or in an accident, the adaptation between brain and body is quick and painless. However, sometimes the missing limb feels permanently clenched in a painful position. In a phenomenon known as “phantom limb pain,” no feedback can be sent to the brain without the physical presence of a limb, and the pain cannot be relieved. For a long while, the cause of the pain was often attributed to psychological trauma or the result of active nerve endings. The ghostly pain was simply a new part of life to get used to.

Then, in the mid-90s, UC San Diego professor and neurologist Dr. V.S. Ramachandran proposed a simple solution: a mirror box. Patients would place an intact limb inside the box with their amputated limb beside it. In a visual illusion, a patient’s hand, for instance, is superimposed on the mirror in the place of the amputated limb and this reflection is enough to allow the phantom limb to “move” and release itself from a painful position.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gc3CmS8_vUI&w=560&h=316]

Fast forward to 2010. Haiti experienced a devastating 7.0 magnitude earthquake that took over 250,000 lives and left more critically injured. Due to the presence of poor infrastructure, many buildings collapsed during the quake, killing and trapping occupants within. The country’s healthcare system, still recovering from two tropical storms and two hurricanes in 2008 at the time, was simply unprepared for another disaster.

Elizabeth Seckel, an undergraduate student and research assistant at the UC San Diego Center for Brain and Cognition with Dr. Ramachandran at the time, remembers the day.

“Everything changed for me when I read that the day following the 2010 earthquake in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, the line for amputations was more than 1,000 patients long. I knew this was sure to increase the prevalence of phantom limb pain, which is what I was studying with V. S. Ramachandran.”

Seckel was interested in experimental psychology and optical illusions for as long as she can remember. She grew up reading , Phantoms in the Brain by Dr. V.S. Ramachandran and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for A Hat by Oliver Sacks. When the time came for her to go to college, it was a simple decision. She chose UC San Diego so that she could perform research with Dr. Ramachandran.

It was within Dr. Ramachandran’s lab that Seckel got to witness the therapeutic use of the mirror box on patients first-hand. There, she also worked on studies that involved apparent motion illusions, tactile illusions, synesthesia, neuroaesthetics, and mirror visual feedback.

However, after reading about the events in Haiti and receiving a flyer on Library Walk that advertised the impending arrival of the Clinton Global Initiative-University (CGIU) conference at UC San Diego, Seckel saw an opportunity to bring her research to the larger community.

“All participants had to make a commitment to do some social good, I knew what mine would be: bringing Mirror Box Therapy to amputees with phantom limb pain in Haiti,” she explains. “It was very important to us to make sure our presence would be helpful and not an imposition so we wrote to local hospitals and clinics, explained what the therapy was, and asked if it would be beneficial if we came and gave talks about Mirror Box Therapy.”

The CGIU was founded by President Clinton in 2007 with the goal of empowering the next generation of leaders from college campuses all around the world. Each year, CGIU hosts a conference open to students, university representatives, topic experts, and even celebrities. Global challenges are brought to the forefront, and this discussion provides a venue through which innovative solutions are proposed. Seckel’s proposal is among 6,250 others that have committed to addressing local issues at universities, in communities, and around the world for the past ten years.

“After receiving the Albert Schweitzer Hospital’s invitation,” says Seckel, “I quickly realized I now had to figure out how to pay for it. Fortunately, UCSD has a lot of research scholarship opportunities, and summer research programs with stipends. Funded by a UCSD Eureka! Summer Research Scholarship, I first traveled to Haiti in September 2011 with four of my undergraduate research assistants to practically implement Mirror Box Therapy at the Albert Schweitzer Hospital and Hanger Prosthetics Clinic in Deschapelles.”

Seckel remembers one patient who experienced extremely debilitating phantom pain, with episodes of severe pain as frequent as five minutes apart.

“He described his phantom foot as immovable and clenched very tightly,” recounts Seckel. “One of the physical therapists introduced him to the mirror where he slowly unclenched his phantom for the first time, immediately reducing his pain. It is amazing to see the ‘aha!’ moments experienced by the patients when the therapy clicks and they begin playing with the mirror–tapping their intact limb and grinning when they feel the tap in the phantom.”

“This experience truly changed our lives. We made lifelong friends and continue the work to this day, six years later.”

Seckel and the other undergraduates also held presentations for the doctors and physical therapists at the hospital. 200 mirror boxes, in addition to prosthetics, were provided to ensure the continuation of treatment after the students departed.

Seckel and the team were awarded a university grant to continue their advocacy for mirror box therapy throughout Haiti and the Dominican Republic. They also joined the University of California Haiti Initiative (UCHI) as part of the UC campuses partnership with Haiti’s largest public institution of higher learning, the Universite d’Etat d’Haiti. Together, these educational centers support the reconstruction of Haiti and work to achieve stability and prosperity for the country in the long-run.

Seckel hopes to encourage a future of socially conscious research and has spoken at the 2012 TEDxUSC and TEDxAFC conferences and the 2013 Ashoka U Exchange, the world’s largest social entrepreneurship education conference. She has also been featured on the Discovery Channel, New Scientist, The Sunday Times Magazine, and Scientific American Mind.

Today, Seckel runs Neurotherapy International, a nonprofit foundation, with co-founder Nicole de Faymoreau with the goal of developing and implementing simple and effective treatments for neurological conditions. She hopes to return to work with Haiti’s Ministry of Public Health and Population to implement Mirror Box Therapy throughout the country.

“I would love to see more clinical trials exploring how to maximize Mirror Box Therapy’s efficacy,” says Seckel. “It has also been found to reduce chronic pain from complex regional pain syndrome and to improve post-stroke motor recovery. What other conditions could benefit from these techniques? There is so much left to explore.”

[hr gap=””]

Resources

- https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2011/jan/30/observer-profile-vs-ramachandran

- https://www.britannica.com/event/Haiti-earthquake-of-2010

- http://www.uchaiti.org/who-we-are/history/

- https://www.clintonfoundation.org/clinton-global-initiative/meetings/cgi-university/2017

- http://imaxwell.typepad.com/blog/2012/12/this-weeks-blog-a-look-at-how-the-next-generation-is-building-socent.html

- http://journals.lww.com/neuroreport/Abstract/1996/10020/Coding_of_modified_body_schema_during_tool_use_by.10.aspx