Lexie Frye Rochfort | Blogger | SQ Online (2014—15)

I just watched Age of Adaline, and I thought to myself: perfect. I’ve been dying to talk about something dumb that happens in a movie, but then they used “almost magical” as their excuse. Too bad, I’m still going to make fun of this movie: beware spoilers.

I just watched Age of Adaline, and I thought to myself: perfect. I’ve been dying to talk about something dumb that happens in a movie, but then they used “almost magical” as their excuse. Too bad, I’m still going to make fun of this movie: beware spoilers.

Fortunately, I already talked about what happens when you get electrocuted; this movie, however, suggests some science talk about electron compression, amperes, and deoxyribonucleic acid. Big words to cover up a lack of knowledge (sounds like what I do). The narrator suggests that getting into a car accident, dying of drowning/hypothermia, and then getting struck by lightning causes “electron compression in the telomeres of her deoxyribonucleic acid.” Sounds sciency, but I’ve been googling for half an hour what electron compression is, and I’ve got nothing.

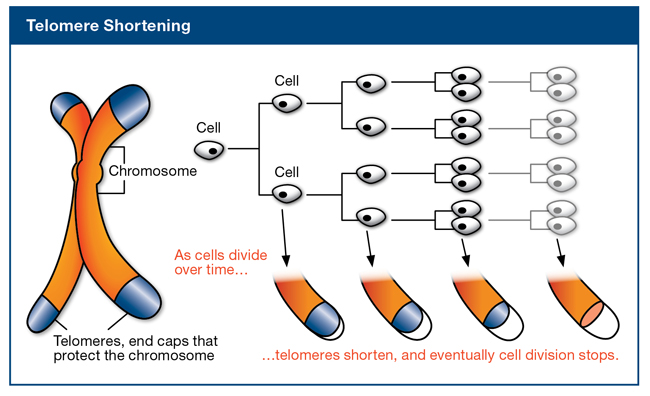

Let’s talk about aging. As a matter of fact, in my molecular biology class, we were just talking about aging and the cause: shortening of telomeres. Each time you make a copy of your genome during cell division, telomeric regions at the ends of the chromosomal strand get shortened because of the nature of DNA replication. Telomeres exists as a repeating sequence of “junk.” Its use is to protect the important coding regions from being lost. The RNA primers that initiate DNA replication cannot bind past the ends of the DNA strand, so each time, between 50-100 base pairs are lost. Going from one fertilized cell to the plethora of cells in the human body, the amount of base pairs lost must be substantial.

Also in my previous article, I mentioned Henrietta Lacks, the woman whose cultured cancer cells still exist today. How come cancer cells don’t die from telomere shortening after constant division? We do have enzymes called telomerase, which attempt to rebuild and extend telomeric sequences. Certain cancers simply promote the expression of telomerase. If Adaline were to have telomerase running around the clock in her cells, she may live forever as a cancerous blob.

Magically, again, she has a similar experience to undo her living forever near the end of the movie, so I guess telomerase was deactivated? Unfortunately, deactivating telomerase does not seem to be a viable treatment for cancer; it just makes the cancer angry. Ok, not really angry, but the cancer does seem to become more aggressive. Using some alternate mechanism to continue to extend telomeres, deactivating telomerase expression actually causes cancer-promoting changes through gene expression. We will certainly find a way to better treat cancer, but telomerase inactivation is unlikely.

There’s just no winning with this movie–it was really bad. I was actually taking someone on a date on her request to see this movie, and it was so boring she fell asleep during it! Bad movie, bad story, bad characters, bad science.

[hr gap=”0″]

Sources:

- https://sqonline.ucsd.edu/2015/04/you-frankenstein/

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3370421/

- http://www.cell.com/abstract/S0092-8674(12)00026-8

- https://pbs.twimg.com/media/CD4x2ifUIAAD57O.jpg

- http://vrp.com/static/images/aug2012nl_telomere.jpg