During an on-campus fire drill in her junior year, recent graduate Syreeta Nolan realized that UC San Diego, like many universities, was asking her to either prioritize her physical health or her education.

At the time, Syreeta did not openly identify as Disabled, despite having chronic illnesses that affected her diet, fatigue, mobility and overall health. Because Syreeta’s symptoms have an internal physiological effect and may not necessarily be outwardly apparent, Syreeta can “pass” as able-bodied. Syreeta is not alone, as 96% of people with chronic illnesses are considered invisibly disabled, a colloquial term used to describe a disability or illness that is not always outwardly obvious. However, after Syreeta transferred to UC San Diego, she felt as if her identity as a Black student researcher was the only one worth centering due to how the university approached the Disability community. At the time, Syreeta never knew the power of owning her disability identity in the midst of her chronic mental and physical health conditions.

For Syreeta, physical activity is often difficult and painful due to her Fibromyalgia and sciatica. Fibromyalgia is a chronic widespread pain in a person’s muscles, ligaments, tendons and bones, while sciatica describes a pain that localizes across the sciatic nerve from one’s lower back and down their legs.

At UC San Diego, students with mobility needs are often given housing accommodations on the first floor both for students’ safety and accessibility. On the other hand, Living and Learning Communities that emphasize culture, representation, and academic success are not necessarily offered on the first floor, even though they are advertised as being offered to all incoming students. This causes a separation between the Disabled community and education.

Syreeta had to choose housing suited for her body’s needs or the Bioscience Living and Learning Community that would introduce her to other new transfer students interested in similar academic pursuits. Because of Syreeta’s desire to connect with a new community and her passion for pursuing higher education, she made the decision to forgo her mobility accommodations and move to the community in the Village. Only later did she find out that the community was located on the eleventh floor.

Syreeta enjoyed her time at the residence and had not run into issues regarding accommodations, until she received an email notifying her about a fire drill scheduled for her building. During the fire drill, all residents were required to take the stairs down to the main floor, walk two more flights up to Ridgewalk to check in with their resident advisors, who gave them the participation incentive of a Kripsy Kreme donut. Being gluten free, there was no incentive for Syreeta, only the knowledge that she would get to Ridgewalk in intense pain and likely be fatigued for the rest of the day.

“Having Fibromyalgia and sciatica, I knew that if I did participate in the fire drill that these conditions would lead to a pain flare up either happening on the way down the stairs, or while I’m going up,” Syreeta explained over the phone to her house liaison, who was responsible for the residents on that floor. During this conversation, she was told that she shouldn’t participate in the drill and instead stay at a friend’s apartment located on a lower floor of the building.

Hanging up, she had a realization: she was a disabled student on the 11th floor with no applicable plan in the case that there was an actual emergency. Many questions surfaced. Why was she being asked to choose between her physical health and a learning community that would engage her intellect? Why did she, as a Disabled student, have to pick one or the other? Why didn’t the academic institution think of these issues proactively, instead of allowing the stress to fall onto her? “As a Disabled student,” Syreeta explains, “I felt like an afterthought that was expendable in the case of an emergency like an unspoken, eugenic lack of policy.”

Disabled students in academia are asked to prioritize either their health or their education instead of institutions setting up systems for students to succeed in both. Syreeta details how we have allowed this to commonly happen in university settings.

Disability in universities is typically seen solely as a medical issue to provide accommodations for, rather than a diverse community to foster. At UC San Diego, the Office for Students with Disabilities (OSD) provides various services, including transportation across campus and modifying meals to accommodate students’ diets, and clearly states that it is not an advocacy agency. However, since Disabled students receive little support and community outside of these accommodations, this mindset fosters the medical model of disability rather than the social model.

The medical model describes that people are disabled by their physical, mental, or sensory differences, and these differences should be fixed or changed by medical treatment. Because this model was historically established by the able-bodied majority, it has been adopted as the norm in many public spaces and institutions, including universities. However, the medical model allows for ableism, the intentional or unintentional discrimination of Disabled individuals, to occur in many contexts.

Syreeta has witnessed the negative effects of the medical model first hand in her developmental psychology class at UC San Diego, which was led by an able-bodied professor. Students were asked to argue both sides of a topic on their online discussion boards each week, and one week the debate presented to the class was: “Should we try to cure autism?”

The CDC defines Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) as a developmental disability that can cause social, communication, and behavioral changes for over 2.2% of adults in the United States. Neurodiversity is a term first coined in the 1980’s that describes that all people have unique differences in their cognitive abilities, including neurominorities like autism.

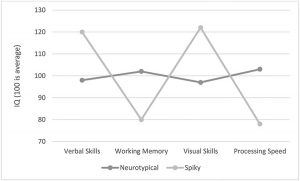

When scoring a person’s verbal skills, working memory, visual skills, and processing speed, a doctor will plot that person’s score on a graph. The majority of the public who are neurotypical will have scores that “flatline” across each skill, with no statistically significant peaks or troughs. A neurodivergent person will have a “spiky profile” with some cognitive skills having immense scores while other skills being significantly lower than their peers. 17% of adults in the United States are considered neurodivergent, and can include a range of neurominorities like autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and Dyslexia. Many people do not know where they lie on the neurodiverse spectrum, as diagnosis is based on the developmental monitoring of a child by their parents, which allows for many missed or delayed diagnoses.

Syreeta’s class conversation surrounding autism frustrated Syreeta, since she is also a neurodivergent woman with ADHD and has experienced the deep-rooted complications of a delayed diagnosis. Syreeta was only just diagnosed with ADHD in February 2021, and while Syreeta felt that she now understood herself more completely, it didn’t erase years of self doubt. In a study that followed a group of 140 girls with ADHD over a ten-year period, it was found that girls are more prone to self-harm than both boys with ADHD and neurotypical girls. Additionally, in a study of 433 college women with ADHD, it was found that many of the girls had a history of violent partners and victimization through their relationships. “To be entirely vulnerable, this was me,” Syreeta comments.

When she then saw this question regarding autism posed to her class, she cringed at its lack of nuance. She proudly lost 2 points on the assignment rather than engage in the ableist argument that they expected her to participate in. Syreeta asks, “Why aren’t we getting Autistic researchers in (class) to present something that would have been so much better?”

Centering Disabled people in conversations surrounding disability advocacy is the basis of the social model of disability. The social model opposes the medical model by describing that disability is caused by the way society is organized, rather than the individual’s impairment or difference. Society deems certain actions, like the ability to walk up stairs or see images on a computer screen, as normal and ultimately ostracizes those who are unable to uphold these actions. Instead of only discussing disability in the context of treatment and a problem to be fixed, the social model asks what society can change in order for Disabled people to have autonomy and self-expression.

As a neuroscience researcher herself, Syreeta explains that this type of ableism is ingrained into the STEM field. For any diversity training, it is expected of our peers to be anti-discriminative. Just as our university encourages anti-racism instead of solely race inclusivity, diversity programs should include anti-ableism. “Do the number of programs, services and spaces equal up between the Disability community and the Black community (at UC San Diego)?” Syreeta asks. “I think that answer is clearly no.”

This lack of recognition, adaptation, and support allows Disabled students to slip through the cracks of education and creates a negative feedback loop for the next generation. While there are 19% of U.S. undergraduates who identify as disabled upon admission, only 34% of these students finish four-year programs in the United States. In the professional research world, reporting disability status has led to the decline of grant money. Research grants received by the National Institute of Health (NIH) awarded 0.7% less grants from 2008 to 2018 to PI’s whose labs indicated disability status. And it might be because of this decline in funding that we are seeing fewer researchers disclose their disability status on NIH grant applications. If post-docs, PIs and faculty members at universities are redacting their Disabled identities to the professional public, this fosters a brittle academic environment for Disabled undergraduates who are left without mentorship or support.

STEM culture has set high expectations of students at the expense of their mental and physical health in order to be competitive in the workplace, and because of this, STEM fails to recognize Disabled people as present in STEM spaces. “The way we exclude disability is actually deteriorating STEM,” Syreeta continues. Researchers and medical students who have first hand experience in the subject they are studying would likely benefit the field. “I would love to have a Disabled doctor, they would know intimately what it means to live with disabilities and the ableism that we face. The empathy and respect Disabled doctors have for Disabled people is phenomenal.” Syreeta says. “But the truth is, it’s not likely to happen because there’s not that kind of respect or support for disability within medical science.” Again, we see more examples of the harm of the medical model of disability to Disabled people, rather than supporting them.

Over the past few years, Syreeta has found the community she had been longing for on #DisabilityTwitter where researchers can gather and speak honestly about the intersection of their identities with the STEM field. On this platform, Syreeta has founded Disabled in Higher Ed which has brought together more than 7,000 Disabled and neurodivergent people as a robust community, who are either well into their careers or are students like her. This created an intersection between #AcademicTwitter and #DisabilityTwitter to discuss the ableism within academia that leads to Disabled students dropping out.

Positive experiences, like these unapologetic conversations in the Disabled community, and negative experiences born from the medical model, like the fire drill at UC San Diego, invoked the importance for Syreeta to openly identify as Disabled. “There’s just a degree of freedom in not having to hide an aspect of who you are,” Syreeta explains. “Fighting against yourself is not going to be a winning battle, because you have to live with yourself. This is what shapes your relationships with the reality around you.” Today, she has embraced her identity as a Black, Indigenous, invisibly Disabled, neurodivergent woman, and feels pride both in herself and her community online.

What does openly identifying as Disabled look like? Syreeta describes that similarly to those in the LGBTQ+ community, Disabled individuals all must face their own internalized ableism before seeing a value in identifying as Disabled. Being part of a community as one accepts their identity is reassuring, although fostering this community is not supported heavily enough within higher education.

Disability culture is often unintentionally suppressed in public spaces due to the medical model’s approach to one’s medical history. HIPAA securities rules were created to electronically protect people’s private health information and punish those who solicit medical information without consent. Although this does preserve medical confidentiality, it also deters public spaces like universities to actively recognize and support Disabled communities.

Syreeta had the opportunity to counter this argument with UC President Michael Drake this spring quarter with the idea of disability pronouns. When she introduced herself, Syreeta stated her pronouns were she/her/hers and her disability pronouns were Disabled woman, invisibly Disabled and neurodivergent. Syreeta explains that she had first heard the term “disability pronouns” during her involvement in disability advocacy programs. Disabled with a capital D acts as a term of identity, for both the user and the people they interact with. Just as the terms Black and Deaf are capitalized with the intention of recognizing community, the pronoun Disabled serves as a way to communicate identity without revealing private medical information.

Throughout this article, Syreeta and her identity as a Disabled woman have been highlighted, not the details or science behind her chronic illnesses. Although Saltman Quarterly blogs serve to explain the science behind student life at UC San Diego, our articles and community can benefit from this separation of medical and social models. It’s these distinctions that will allow the Disabled community to exist in STEM spaces without the consequence of losing accommodations or revealing medical information that would be rather privatized. With more and more platforms on campus recognizing and embracing these nuances, communities will continue to intersect and grow.

—

Syreeta has worked diligently in the past year to replace long-lasting ableism with community support on the UC San Diego campus. Syreeta coordinated and commissioned a world renowned artist who had initially designed and put together the Marshall College mural, entitled “American Progress – The People don’t Matter, to incorporate the Black Disabled Lives Matter symbol within their pre-existing mural, which uses an infinity symbol, within a Black Lives Matter fist, to represent neurodiversity. She developed, coordinated and hosted many of the 14 events she curated along with the former UCSD delegation of the UCSA Disability Ad Hoc Committee for Disability Awareness track during Spring Break 2021. These events sought to bring awareness to Disabled students that we have a Disability community and to bring awareness to the UCSD community that the Disability community is here. She proposed and now helps with coordinating an art installation piece that celebrates the Disability community at UCSD and she will continue to serve on this community as an alumna. Syreeta hopes to see a space for disability pronouns on future UC applications and integrated across campuses. One legacy she leaves UC San Diego as she graduates is the installation of a disability studies minor, which will be available for future students to pursue in the Ethnic Studies Department. To learn more, please feel free to read her article entitled “The Compounded Burden of being a Black and Disabled Student during the Age of COVID-19” in Disability and Society.

Sources:

- https://invisibledisabilities.org

- https://medlineplus.gov/sciatica.html

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/fibromyalgia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354780

- https://osd.ucsd.edu/_files/OSD-Brochure-7.6.2020.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6312522/

- https://www.autistichoya.com/p/ableist-words-and-terms-to-avoid.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/facts.html

- https://www.neurodiversityhub.org/what-is-neurodiversity

- https://academic.oup.com/bmb/article/135/1/108/5913187

- https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/screening.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/screening.html

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0886260515586371

- http://www.disabilitynottinghamshire.org.uk/index.php/about/social-model-vs-medical-model-of-disability/

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ableism

- https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=60

- https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0228686

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00887-8

- https://twitter.com/DisInHigherEd?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Eauthor

- https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/security/laws-regulations/index.html

- https://signhealth.org.uk/resources/learn-about-deafness/deaf-or-deaf/