The healthcare system regularly fails women of African ancestry, transgender patients, and HIV+ individuals, calling for reform in access to treatment, a restructuring of the healthcare referral process, and an increase in awareness of patient needs.

What path would you take if you felt like you couldn’t trust your own doctor? Many historically marginalized groups often face bias from medical professionals, resulting in inadequate treatment and even fatal outcomes.

PHOTO BY SAM ZILBERMAN

For years, Amira Lewally had lost the ability to hear in one of her ears. As an African American woman, she was wary of doctors and was always frightened that they would not take her seriously. Her primary care physician diagnosed her with allergies, yet her worsening symptoms and her continued doubt led her to take matters into her own hands. She went to several medical professionals, yet specialist after specialist continued to insist that her symptoms were simply allergies. Lewally eventually stumbled across an article that matched her symptoms, and finally found an ear, nose and throat doctor (the third one she had been to) who diagnosed her with a cerebrospinal fluid leak.

Lewally’s testimony, published in the LA Times, is not unique, and reveals a grim reality about Western medicine–it caters primarily to white, cisgender men. However, all patients deserve a clinical experience in which doctors are unbiased: aware of their patient needs and takes patients seriously.

Researchers at UC San Diego have begun to tackle this issue, focusing specifically on women of African ancestry with breast cancer, transgender individuals, and HIV positive patients with cancer. These researchers are exposing age-old biases, identifying core issues in the current system, and providing feasible solutions to improve medical care for minority groups. Healthcare prides itself on its ability to care for all, and it’s time to make that claim a reality.

BREAST CANCER SURVIVAL

According to breastcancer.org, breast cancer is a common form of cancer among women, affecting around 1 in 8 women in the United States, particularly women of African ancestry (WAA). Although breast cancer has been well-researched over the past few decades, disparities among rates of diagnosis and survival for the disease still exist.

Yilin Xu, a Biochemistry/Chemistry major at UC San Diego, delved deeper into this topic through her research on the correlation between BRCA mutations and survival disparities among women of African descent.

Mutations in the BRCA genes are the main causes of hereditary breast cancer in women, according to the Illinois Department of Public Health. When there is a mutation in the DNA coding for BRCA proteins, the resulting proteins cannot repair DNA or suppress tumors as they normally would, resulting in the development of cancer. Women with African ancestry are more likely to have the BRCA mutation and are at higher risk of developing triple-negative breast cancer, a highly aggressive form of breast cancer that is difficult to treat.

To quantify the obstacles faced by WAA with regard to breast cancer risk and diagnosis, Xu drew comparisons between these women and non-Hispanic white women by compiling data from various research papers. In doing so, she was able to draw several conclusions about the correlation between the BRCA mutations and survival rates of breast cancer for WAA.

Primarily, she found that WAA are diagnosed with breast cancer less frequently, even though they face a higher mortality rate. Women of African ancestry have a ten-year survival rate of 64% compared to 81% for non-Hispanic white women.

How might we address these disparities in survival rates? Xu proposes multiple avenues for improving the situation. For starters, she states that health education is a necessity. Informing women, specifically those with African ancestry, about breast cancer-related issues shows potential in dramatically decreasing the gap in survival rates. Additionally, Xu says providing cancer diagnostic resources such as free mammograms would allow many women to discover breast cancer at an earlier stage. She also emphasizes that genetic testing is a useful tool for preemptive diagnosis and treatment, as 69% of those who carry the BRCA mutation receive a triple-negative breast cancer diagnosis.

Eliminating systemic biases from society is arduous, as they are often ingrained in our subconscious. But by promoting awareness of these issues, we come one step closer to making the medical world a better place for women of African ancestry.

GENDER TRANSITION PROCESS

Transgender (‘trans’) patients are another marginalized group in the medical field. Trans individuals are those who identify with a different gender than the one they were assigned at birth. They have the option to go through medical treatment in order to transition; this process often involves hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgeries in order to achieve the physical and hormonal makeup of the gender with which they identify.

Unfortunately, these procedures are complicated, as trans patients usually deal with unsafe medical environments. 85% of trans patients are misgendered in clinical settings because many professionals are unaware of the social etiquette and medical needs of these individuals. Furthermore, there is a systemic lack of patient autonomy for trans patients and no clear route through the transition process.

David Everly, a Public Health major at UC San Diego, addresses these disparities through his research on specific medical practices that can improve both the transition process and general medical care for transgender patients. Through a systematic review, Everly identified papers containing the “best practices” that address parts of the trans clinical experience.

Currently, to be eligible for gender transition services, clients must meet criteria for a diagnosis of “gender dysphoria.” This is known as the gatekeeper model, and involves a meeting with a psychiatrist, approval by a psychologist, and a year of hormone therapy before eventually beginning the transitioning procedures. By placing roadblocks in the transition process, this model limits the autonomy of transgender people and is therefore viewed as unethical by many in the trans community. Instead, Everly proposes the informed consent model. This model involves a general practitioner providing adequate information to a person before allowing the individual to make an informed decision regarding gender-affirming medical treatment, providing medical equity and autonomy for trans patients.

The medical system can feel like a maze for many transgender patients. Making the system more navigable is essential to ensuring patient wellbeing.

Everly’s next suggested practice is the multidisciplinary medical home, a team based health care delivery model where specialties collaborate to provide their patients with the best care. Trans patients are often overwhelmed with referral processes as a patient sometimes requires multiple referrals for only one of the many procedures they undergo. Therefore, a “medical home” in the form of a vetted referral system would be effective. This system greatly lowers the risk of unfavorable experiences with providers due to a lack of education or a lack of cultural competency training. The healthcare company Kaiser Permanente has already been implementing this model through the opening of a Multi-Specialty Transition Department at several locations.

Medical professionals’ awareness of these disparities–and how to alleviate them–is a must. Without the types of changes highlighted by Everly, trans patients will continue to experience the repercussions of a system not tailored to suit their needs.

CREATING TOOLS TO HELP

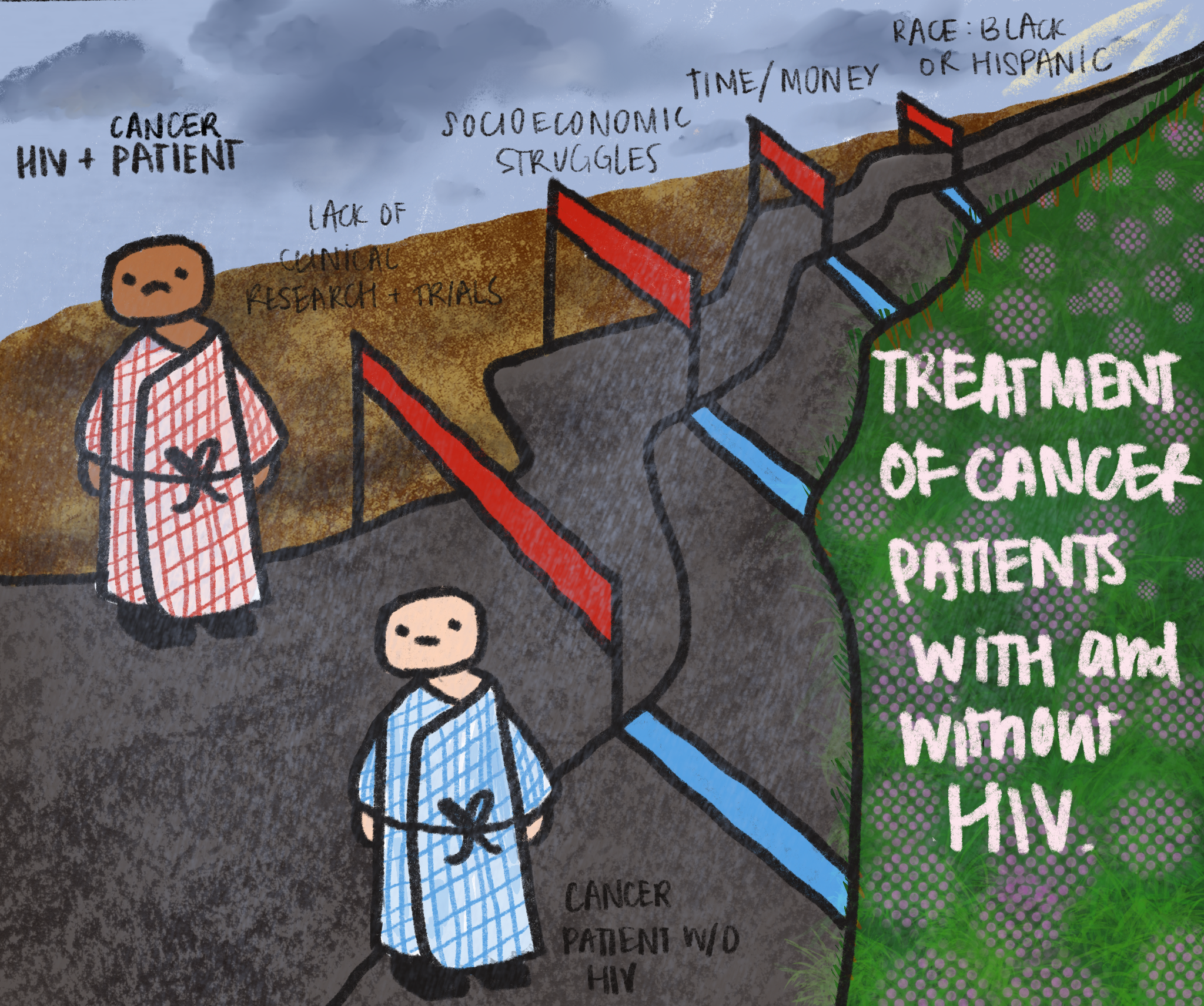

To this day, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a major global health issue. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, over 38 million people worldwide were HIV+ in 2019. HIV attacks the immune system and increases patients’ susceptibility to other diseases, including cancer. Unfortunately, HIV+ patients with cancer face disparities in healthcare treatment compared to other cancer patients.

Rowan Ustoy, a UC San Diego General Biology major, conducted a literature review to look into the barriers that HIV+ cancer patients face. Based on Ustoy’s research, HIV+ patients suffer from higher rates of cancer but lower rates of adequate treatment. Why? Like the cases of women of African ancestry and trans individuals, the answer stems from a lack of awareness of patient needs.

Alarmingly, many physicians lack knowledge about the treatment of cancer patients with HIV. Part of this may be due to the fact that 45% of oncologists (cancer specialists) do not discuss treatment with a patient’s HIV specialist. Furthermore, HIV patients have been, and continue to be, excluded from cancer clinical trials.

From lack of research to high-cost treatment that many cannot afford, HIV+ patients with cancer face many hurdles in getting any access to help.

This lack of inclusion has resulted in a scarcity of data regarding the needs of such patients. Consequently, a shocking 75% of physicians report lacking confidence in cancer treatment approaches for their HIV+ patients. This can be life-threatening, as antiretroviral therapy (ART) drugs, the primary treatment for HIV, are known to often clash with cancer treatments.

In addition to the factors mentioned above, many HIV patients face socio-economic struggles. HIV is a lifelong disease and requires daily medication, and cancer requires intense treatment involving multiple hospital stays. Treating these diseases demands both time and money, and many of those afflicted lack the funds necessary for these treatments. Furthermore, HIV+ patients are more likely to be non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic. These are groups that are disproportionately less likely to receive treatment, as they lack insurance and therefore access to healthcare.

Is there a way to overcome these challenges? Yes, and one may look to the promising advancement in anal cancer treatment as proof. Anal cancer has been well-documented in clinical guidelines, allowing HIV+ patients to obtain quicker diagnoses and more specific treatment options. Knowing this, we can be confident that it is indeed possible to lessen the disparities between HIV- and HIV+ cancer patients.

In order to extend the same chances of survival to HIV+ patients with other forms of cancer, Ustoy emphasizes the necessity of promoting clinical trials that include HIV+ patients and those that focus on the link between HIV and cancer.

ADVOCATING FOR HEALTH EQUITY

Medicine, just like the rest of society, is biased. Society’s racism, transphobia, and HIV stigma are rampant, and solving these issues is complicated. In 2020, America faced a wake-up call to the inequalities and injustices carried out against its historically marginalized populations. The murder of George Floyd shed light on police brutality against African Americans. The Trump administration proposed a new rule that would allow sex-segregated shelters to refuse service to transgender people. Eight in 10 people in the US with HIV continue to feel internalized stigma while receiving treatment, a direct result of the discrimination they face.

Under these circumstances, it is more important than ever for medical professionals to take the appropriate steps to tackle these injustices. Providing healthcare resources to underserved communities, furthering inclusion of minorities in clinical trials, and providing quality care that respects patient autonomy are some of the first steps to providing a more inclusive healthcare system.

By acknowledging these disparities and spreading awareness that they exist, we as a society can take the first steps towards closing the gaps in healthcare equality.

WRITTEN BY RACHEL LAU & NIKHIL RAO

Rachel Lau is a first year student majoring in Neurobiology. Nikhil Rao is a second year student majoring in Molecular and Cell Biology.

FROM UNDER THE SCOPE VOL. 11

To read the original version, please click here. To read the full version on our website, please click here. To read more individual articles, please click here.