In the landscape of mental health, scientists are researching how upholding mental well-being can impede or even cure disease.

A tired student works on schoolwork late into the night, illuminated only by the harsh light of their computer screen.

PHOTO BY SAM ZILBERMAN

This fall, 16,700,000 students began another term of their undergraduate degrees. In October 2020, 31,842 Tritons began an intense online quarter filled with midterms, assignments, projects, final exams, and extracurriculars–all of which can combine to form an alarming recipe for stress and potentially poor mental health. This precarious balance between academics and mental health is often difficult for students to manage, as reflected in the popularity of on-campus resources such as Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS). That said, what happens after an individual is diagnosed with anxiety or depression? Upon receiving a diagnosis, many may initially hesitate before asking their physician if there is a “pill for that.” In fact, according to a report released in March 2020 by the National Center for Health Statistics, the rate of antidepressant use in the United States increased by 400% between 1988-1992 and 2005-2008 in people ages 12 years and over. This alarming increase in the number of people turning to prescriptions to improve their mental well-being leads us to the following question: what does a healthy balance between prescribed and self-initiated care look like?

GOT BIOLOGY?

Over the last several decades, researchers have slowly uncovered a number of biological pathways that directly tie into our mental well-being. From the development of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for treating depression to the role of lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder, the success researchers have had in utilizing these pathways to treat mental illnesses has somewhat reinforced our culture’s enthrallment with prescriptions. After all, prescriptions initially seem to offer the most direct way of changing our mind’s biological and chemical landscape. The power of the pill is nothing short of immense–so much so that it has influenced our society’s understanding of what recovery looks like.

Here at UC San Diego, researchers across campus are working in a variety of ways to better understand this biochemical aspect of mental wellbeing and how, if at all, we can influence it. One such group is the Spitzer lab, where integral research is being done to identify a biological pathway implicated in PTSD.

THE SPITZER LAB

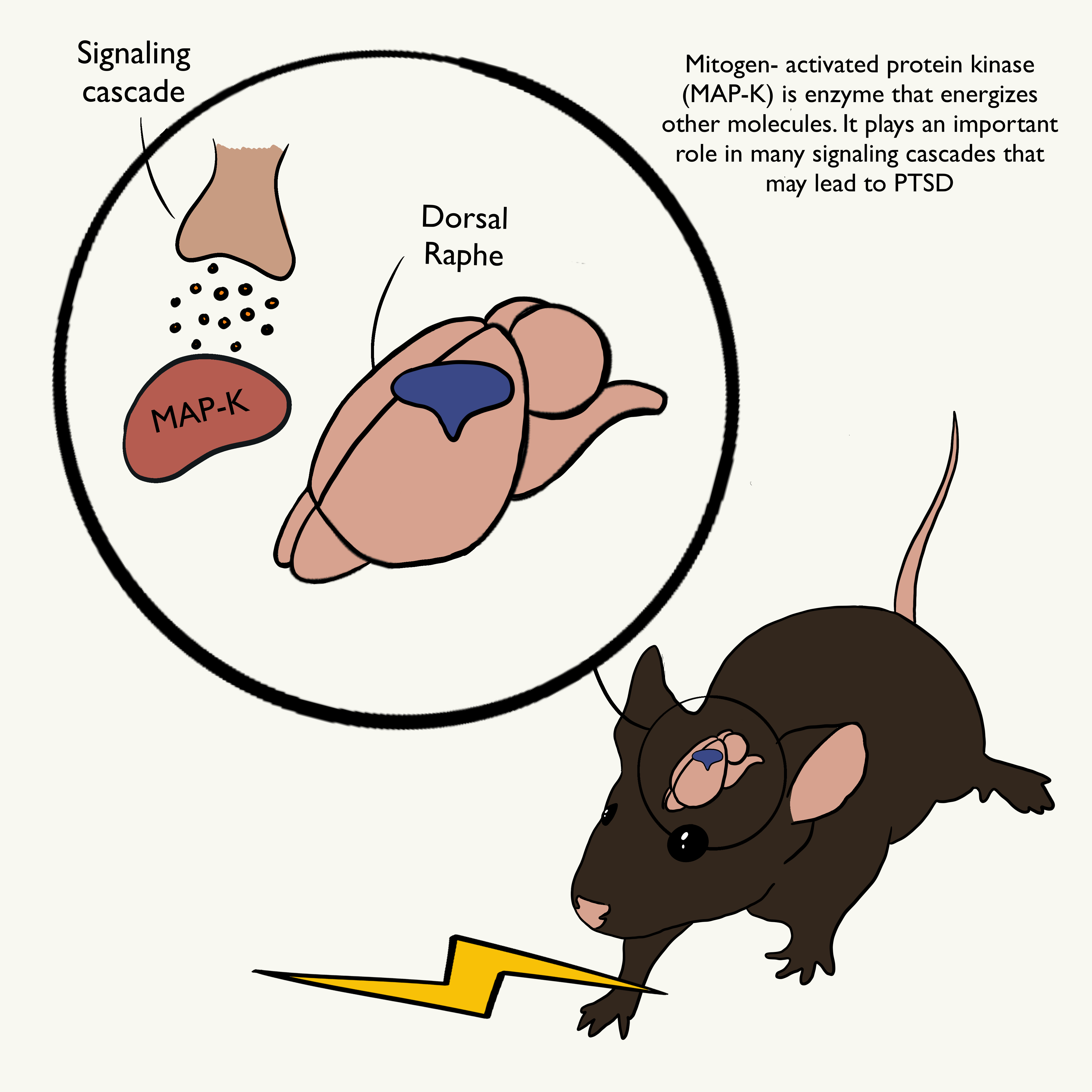

Under the guidance of Dr. Huiquan Li, UC San Diego alumnus Wuji Jiang worked in the Spitzer Lab and conducted research on the possible connection between neurotransmitter switching, or when one neurotransmitter is replaced with another, and harmful outcomes such as PTSD result. By associating a specific neurotransmitter change with the onset of PTSD in mice, Jiang and the Spitzer Lab hoped to develop a biological explanation for PTSD in humans.

In order to induce PTSD, the mice were placed into a box which periodically delivered shocks, stressing them to the point of traumatization. Jiang then tested mice for “freezing behavior,” characterized by the mice’s inability to move during re-exposure to a trigger, as an indicator of PTSD. Once this behavior was confirmed in all the mice, the researchers analyzed each mouse’s brain for a neurotransmitter change by measuring neurotransmitter levels. To measure the neurotransmitter levels, Jiang used an antibody targeting the neurotransmitter-producing enzymes and measured its growth via a process called immunohistochemistry (IHC). The researchers reasoned that detecting an increase in these enzymes via IHC suggested that more of a particular neurotransmitter was being made, indicating a neurotransmitter switch had occurred.

It turned out that Jiang did find a switch: from glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter, to GABA, an inhibitory one. Despite successfully investigating one notable hypothesis, the lab has yet to find an explanation for why this switch occurred. In spite of this frustrating aspect of science, Jiang believes that the Spitzer lab should persist in their search for this molecular explanation in order to gain a stronger biological understanding of mental well-being. By finding a biological response to PTSD with the neurotransmitter switch, the Spitzer lab’s work reinforces the validity of the connection between mental health and the brain’s biochemistry, a connection which prescriptions successfully utilize.

Therefore, Jiang’s research highlights the importance of prescribed care, or the care prescriptions provide for our mental health, as a potential tool for undergraduate students. Although inconclusive, Jiang’s work shows us that an assortment of neurotransmitters and molecules play a key role in determining our mental well-being, as seen in conditions like PTSD. While the most obvious takeaway from this research might be the direct approach of prescriptive care, this study’s insight leaves another potential research question on the table: can self-initiated care, through practices such as meditation, positively impact our mental health? Can we self-initiate and activate the influence of these molecular pathways through practices such as meditation, and thus move away from prescribed care as a primary form of treatment?

When a mouse gets repeatedly shocked, it develops PTSD. The Spitzer Lab delved deeper and found that in the mice’ brains, there was a neurotransmitter switch from glutamate to GABA.

SELF-SUPPORTING MENTAL HEALTH

Through mindfulness exercises such as prayer, yoga, and tai chi, humans have consistently utilized methods to alleviate distressing emotions, from angst to anger. This leads one to wonder: can we improve our society’s rapidly declining mental health by incorporating these centuries-old practices?

While mindfulness cannot remedy all mental health conditions, the benefits of prioritizing mindfulness in our daily lives are becoming increasingly clear, as it provides a level of autonomy beyond the effects of any pill. Located on UC San Diego’s campus, Debra Lindsay, a graduate student under Dr. Karen Dobkins’ mentorship, is looking at the effect of self-confidence on overall mental wellbeing.

HUMAN EXPEIENCE LAB

In September of 2018, Lindsay and her team recruited 338 UC San Diego undergraduates to participate in a study researching the relationship between positive self-reinforcement on overall mental wellbeing. Lindsay first had the participants take an initial personality test that identified their “top strength,” such as being funny, and “bottom strength,” such as being empathetic. Lindsay also measured the participants’ baseline wellbeing through self-reported surveys and established measures of happiness and self-esteem using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) symptomology for depression.

A young woman practices yoga while holding a prescription bottle. The Spitzer Lab and Human Experience Lab show that mental health is a multifaceted entity that can be maintained in a well-rounded way.

Lindsay then divided the participants into two groups: the first group would be told the truth about what their top strength was, and the second group who would be lied to and told that their bottom strength was their top strength. Lindsay instructed all participants to deliberately use their “top strength” over the course of a week and be aware of how this affected their mental well-being. Lindsay predicted both groups of participants would experience a positive increase in their wellbeing as a result of exercising their “strength.” She hypothesized that a participant’s resulting belief in themself would have a positive effect on their mental health.

A week later, the participants returned to the lab and filled out another self-reported survey to re-assess their mental wellbeing. The results were intriguing–Lindsay found that most of the participants who reported an improved mental wellbeing believed that their incorrectly assigned character strength was their true top strength. Lindsay’s results suggest that we do have some degree of autonomy over our mental health, as we can fortify our mental well-being just by increasing self-empowering behaviors such as working on positive aspects of ourselves.

This leads us to ask a final unanswered question: do we have enough autonomous control over our mental well-being to consciously protect it from mental illnesses, or must we still depend on directly influencing our biological pathways via medications and external care?

A SYNERGISTIC APPROACH

As seen by these questions about the prevention and development of mental health illnesses, there is still much to be answered regarding the level of control we have over our mental well-being. The conclusions drawn by both the Spitzer Lab and The Human Experience Lab suggest a partial answer to these questions, showing that both prescribed and self-initiated factors should be considered when developing a well-rounded regimen for effectively maintaining a positive wellbeing. This being said, how does this research apply to the mental well-being of the average college undergraduate?

The Spitzer Lab shows us that basic emotions like stress are rooted in an intricate system of biological pathways we have traditionally addressed with medicine. While it might be impossible for us to control the outcome of these pathways once activated, can we attempt to mitigate the initiation of these pathways by reducing our stress levels? Yes! The Human Experience Lab suggests that simple actions like self-empowerment can have a significant positive impact on overall mental well being. In other words, although we may not have complete control over how a biological pathway proceeds, we might have some control over when these pathways are activated simply by treating ourselves with kindness.

Unlike molecular pathways, self-care doesn’t need to be complex and can be as simple as going for a walk, drinking enough water, calling a friend, reading a book, or stepping outside for a breath of fresh air. The Spitzer and Human Experience Labs’ projects show that both prescriptions and self-care practices can help our mental well-being, suggesting that our mental health is optimized through a combination of approaches rather than a singular investment. Midterms, projects, finals, and interviews may come and go, but our mental health is important for life. Ultimately, if you are contemplating between taking the medication or doing the meditation–why not consider both?

WRITTEN BY IAN FOSTH & VARSHA MATHEW

Ian Fosth is a first year student majoring in Neurobiology. Varsha Mathew is a second year student majoring in Molecular and Cell Biology.

FROM UNDER THE SCOPE VOL. 11

To read the original version, please click here. To read the full version on our website, please click here. To read more individual articles, please click here.