When the human body is injured, many mechanisms and pathways are activated in order to remedy the situation. One of the most visible and well-known processes is inflammation, a response to tissue damage which often manifests as angry, warm, and red swelling around the site of injury. In the case of diseases such as influenza, inflammation can occur throughout the body, elevating body temperature and producing fever. All forms of inflammation are part of the body’s natural immune response, a means of combating and preventing different types of infection.

Blocking infection is primarily accomplished through heat: the warmth felt in forms of swelling and fevers are both utilized to produce an abnormally hot environment that indiscriminately kills pathogens. Because inflammation does not target or recognize a specific type of microorganism, it comprises part of the body’s innate immune response, a general system which fights against infectious agents. Inflammation is also one of the earliest immune responses, as its action precedes any pathogen-specific targeting or cell-mediated immune responses. Inflammation is a complex reaction which will be outlined and simplified throughout this article. A discussion of acute and chronic inflammation in addition to an examination of a recommended anti-inflammatory diet will follow. Links for more in-depth reading and further research are provided at the end of the article.

The inflammatory response is produced by an association of different molecules in the body known collectively as the inflammasome complex. This aggregate aids in the production of specific cytokines, which are proteins in the body that participate in cell signaling. Interleukins are a specific type of cytokine that is known to be involved with the inflammatory response. Prior to any swelling and tell-tale redness, pro-inflammatory interleukins are released from cells, provoking the process of pyroptosis, an inflammation-specific programmed cell death for infected cells.

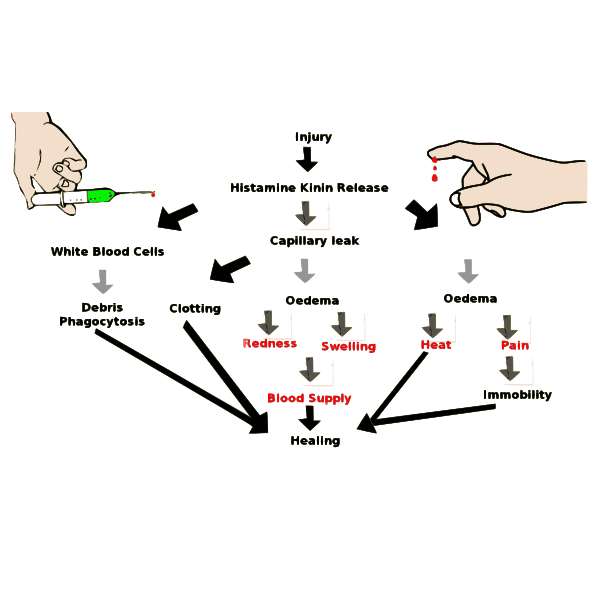

There are two different types of inflammation, acute and chronic, and each has very different implications for the body. Acute inflammation is the more common condition of the two and is part of a normally functioning immune system. Its presence is necessary to hamper infection and to stimulate healing. Upon injury, blood vessels around the site widen in order to accommodate an increased flow of blood from the heart. White blood cells are then recruited to the site in order to fight infection with cytokines. These actions cause the recognizable reddish swelling of inflammation. As healing begins, acute inflammation diminishes and eventually disappears.

Chronic inflammation, however, is characterized by its persistence in the body even after an ailment has been rectified. This long-term form of inflammation produces a constantly hyperactive immune system with greatly elevated amounts of white blood cells. This condition arises from a perceived threat of infection despite the lack of any infectious agents. As a result, white blood cells, which have nothing harmful to fight against, begin attacking the body’s own tissues and organs. This is what occurs in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease.

Another condition linked to chronic inflammation is atherosclerosis, a disease in which excess white blood cells, fatty acids, and cholesterol accumulate in the arteries. These components together constitute plaque, which is incorrectly designated as a foreign invader or pathogen by the body. This is a consequence of a hyperactive immune system. As a result, white blood cells attempt to separate this plaque from blood by constructing a barrier. However, if the structure breaks, the plaque mixes with the blood and forms a blood clot, preventing the flow of blood through that artery. If blood flow to the brain or heart is restricted as a result, a stroke or heart attack may ensue.

The effects of both chronic and acute inflammation have led some individuals to try and reduce inflammatory effects such as swelling. A popular combative method is the anti-inflammatory diet, which promotes the consumption of certain foods while limiting the intake of others, in order to mitigate inflammation. Omega-3 fats, which are readily found in salmon and blueberries, tend to protect the body from inflammation, while trans and saturated fats do not. Consequently, most anti-inflammatory diets incorporate protein from fish and nuts, rather than from red meat as it is high in saturated fat content. Fresh fruit as a source of sugar and leafy greens, such as kale, for iron are also prominent features of the anti-inflammatory diet. Fried foods, sugary drinks, and margarine are all (mostly) avoided. Though diet alone cannot prevent inflammation, it can allow the immune system to function at full capacity while also mitigating plaque buildup that results from fatty foods.

Inflammation is a sophisticated and broad immune response that is normally used to protect the body. In most cases, the heat and elevated white blood cell count characteristic of acute inflammation are enough to alleviate or prevent infection. However, in some cases, inflammation can become detrimental and actually result in negative bodily consequences. While prolonged inflammation has the capacity to become harmful, its presence is nonetheless vital for a properly functioning immune system.

[hr gap=”0″]

- https://vector.childrenshospital.org/2018/02/mda5-autoinflammatory-disease/

- https://courses.lumenlearning.com/microbiology/chapter/inflammation-and-fever/

- https://www.cbhs.com.au/health-well-being-blog/blog-article/2015/01/09/acute-vs-chronic-inflammation

- https://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-disease-overview/ask-the-doctor-what-is-inflammation

- https://www.livescience.com/52344-inflammation.html

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/248423.phphttps://www.nature.com/articles/548534a