MARY LOMBARDI | BLOGGER | SQ ONLINE (2019-20)

Studying and practicing medicine hasn’t always been so glamorous. For hundreds of years, the ancient Greeks used to taste urine to diagnose diabetes, with sweet-tasting urine being its indicative cue. (1) I always hear complaints from people these days when they have to pee in a cup for the physicians to run some tests. But even louder, I can hear those historic greek physicians rolling in their graves.

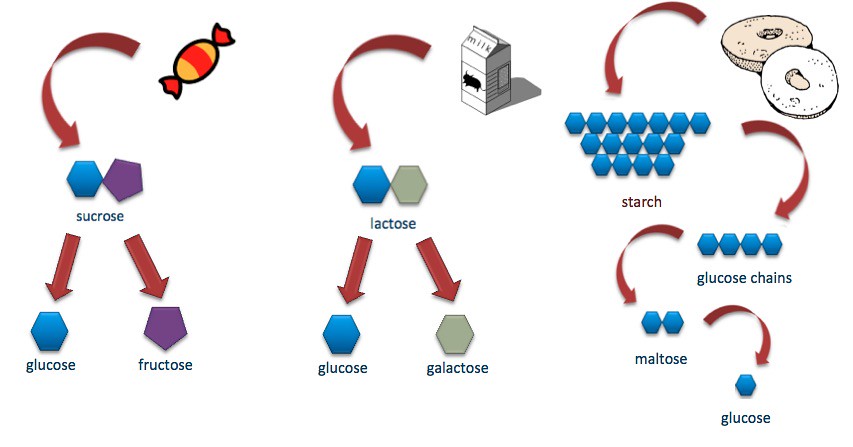

For those who are curious and likely puzzled, you might be wondering how this obsolete diagnosis makes sense (and probably why I wrote about it). Well, sweetness indicates the presence of sugar. And excreting sugar points to an improperly functioning kidney. Normally, the kidney reabsorbs any sugar residing in the urine that has not already been taken up for energy or stored as fat. But when it fails, and in combination with when blood glucose gets too high, glucose passes through the body’s renal system unabsorbed and is excreted into the urine. In the early 1900s, the hormone insulin was discovered and identified for its crucial role in controlling the amount of the sugar glucose, specifically in the blood.

Now, controversy encircles this topic of insulin discovery (and use). Declarations have bubbled to the surface over the years of possible earlier discovery of insulin from other research scientists (stay tuned). Insulin’s discovery endured a long-winded journey, which challenged and frustrated researchers from around the world despite their encouraging findings and additions to pancreatic knowledge at the time. (2)

But first, this controversial discovery requires an understanding of the role of insulin and how it plays a part in the condition of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes mellitus encompasses a group of diseases in which the body fails to produce or respond to the hormone insulin. This results in abnormal metabolism of carbohydrates and elevated levels of glucose (sugar molecules) in the blood and urine. Carbohydrates, the primary source of sugar for the body, initiate the release of insulin upon consumption. The presence of insulin signals cells to absorb the glucose from the bloodstream. Excessive intakes of sugar provokes the body to release greater amounts of insulin, and over time, the body becomes unresponsive or resistant to the constant insulin signal. This manifests as the excretion of sugar and is diagnosed as Type 2 diabetes. On the other hand, Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease in which the body’s immune system attacks healthy cells in the body. In this case, the immune system specifically attacks and destroys the insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas. Daily injections of insulin serve as the main source of treatment, as without it, this condition is fatal. (3)

In the late 1800s, Eugène Gley, a French researcher, decided to test a hypothesis formulated by researcher Gustave-Édouard Laguesse that secretion of a substance capable of preventing the elimination of glucose through the urine might exist. He first isolated a specific tissue relating to insulin in the form of an extract. The tissue was from the pancreatic islets- a group of cells in the pancreas that contain alpha cells (glucagon-releasing) and beta cells (insulin-releasing). The acquired aqueous pancreatic extract of specifically the beta cells (insulin-releasing) was then administered via injection to diabetic dogs with surgically removed pancreases. The pancreas plays an important role in maintaining the body’s blood glucose balance. Without a pancreas, blood sugar is high due to the absence of insulin. But with the injection of this extract containing insulin-releasing cells, Gley noted that excretion of glucose into the urine reduced and the symptoms of diabetes significantly improved. (4)

But after 1890, Gley suddenly ceased his experiments. He wrote a report of his findings sealed within an envelope and handed it over to the Société Francaise de Biologie (French Biology Society) in 1905, with the recommendation that it be opened only upon his explicit request.

10 years later Frederick Banting and his 22-year-old assistant Charles Best, under the Directorship of John Macleod at the University of Toronto, performed a similar experiment as Gley (without having heard of him or his work). They also successfully collected an extract that dramatically lowered the blood sugar levels of diabetic dogs.

Banting, out of nervousness and inexperience, did a poor job delivering the paper at a conference of the American Physiological Society at Yale University in 1921 and the audience was highly critical of the findings presented. Banting and Best’s director John Macleod joined the discussion in attempts to rescue Banting from the scathing commentary. After this fiasco, Banting became convinced that Macleod had stepped in to steal the credit from him and Best, and relations between the two began to deteriorate. (5)

Macleod invited James Collip, a biochemist to help Banting and Best with the purification of their extract. Collip’s breakthrough was the use of alcohol in slightly over 90% concentration to solidify the active ingredient (insulin) in the extract. But he decided he would only share this method of producing a pure extract of insulin with Macleod. In 1923, Macleod represented the group, announcing to a conference that they had discovered the antidiabetic agent- insulin.

In 1923, Frederick Banting and John Macleod received the honorary Nobel Prize in Physiology & Medicine for their discovery of insulin.

After Frederick Banting and John Macleod made their discovery known to the world, Gley revisited his experimental findings with shock. He gave the order to the Société Francaise de Biologie to open the letter of his reported findings from his experiments. The letter disclosed that he had discovered insulin without knowing it!

Gley never offered an explanation as to why he sealed his experimental findings away rather than publish them, and it remains a mystery to this day.

The prize aroused a lively and controversial debate, in that four pivotal research scientists faced exclusion from discovery credit. Banting and MacLeod, the winners of the Nobel Prize, decided to divide their prize with James Collip and Charles Best, as these two researchers had worked right beside them. This, however, officially excluded the two other researchers from receiving credit for the discovery of insulin. (6) The reason for the exclusion of researcher Canada PaulescuРwho concluded that the injection of an aqueous solution of the pancreatic extract allowed an improvement in experimentally induced diabetesРis unknown. And Eug̬ne Gley, to his own frustration, faced exclusion due to the decision to conceal the findings of his unknowingly successful experiments.

Today, the controversy adamantly endures, through insulin production and sale. The patent for insulin, as mentioned previously, was sold for $1 to the University of Toronto upon discovery. Frederick Banting and John Macleod refused to put their names on the patent and make a profit from it, as their intention was to make this anti-diabetic treatment available to all.

Ninety-eight years later, headlines break out in a state of desperation these Nobel Winners did not envision. “Americans are dying because they cannot afford their insulin” embodies this crisis. (7) Type 1 diabetes necessitates that patients take daily insulin injections to survive- but what if a patient cannot afford it?

Since the discovery of insulin, several companies have produced their own brand of insulin and constructed their own price points. However, as inflation rises and company competition increases, prices consequently skyrocket. Patients with Type 1 diabetes typically require two to three vials of insulin per month, whereas patients who are more resistant to insulin (such as those with Type 2 diabetes) may require six or more. Prices range from $200 to $400 per vial depending on brand and potency. (8) In 2009 it cost $225 (on average) for insulin every 3 months; in 2019 the cost shot up to $1800 (on average) for insulin every 3 months. (9)

Today, Colorado is the first in the nation to enact legislation aiming to shield patients from dramatic increases in insulin prices. In early 2019, a new law capped co-payments (fixed amounts a person pays for covered medical services) for the lifesaving medication at $100 a month for insured patients, regardless of the amount of insulin they require. Insurance companies will have to pay the remaining balance. (10)

Ultimately, the profound identification of the body’s insulin-producing beta cells enables physicians to properly diagnose their patients and offer treatment for those with diabetes. The discovery of insulin has saved millions of lives and will continue to benefit lives indefinitely. Fortunately for humanity, brilliant people tend to put their heads together. Unfortunately for humanity, certain people (or companies) tend to treat healthcare as a marketing business.

This is a very “cup half empty, half full” type of scenario. This incredible revolutionary finding certainly transcends the ancient Greek method, but today it’s coupled with the misuse of treatment production. How can we alleviate this situation? What do you think?

- https://academic.oup.com/jhmas/article-pdf/48/3/253/9838324/253.pdf

- https://www.businessinsider.com/insulin-price-increased-last-decade-chart-2019-9

- https://www.diabetesresearch.org/diabetes-statistics

- https://www.goodrx.com/blog/how-much-does-insulin-cost-compare-brands/

- https://www.healthline.com/health/difference-between-type-1-and-type-2-diabetes

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/317484.php

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6205949/

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1923/banting/lecture/

- https://www.npr.org/2019/05/24/726817332/colorado-caps-insulin-co-pays-at-100-for-insured-residents

- https://www.sciencehistory.org/historical-profile/frederick-banting-charles-best-james-collip-and-john-macleod