Imagine a quiet night in. You sit with your headphones on as music blasts in your ears, staring at your computer screen in the effort to submit your homework before midnight strikes while your roommate lies on their bed and scrolls through their phone. As you contemplate the next homework question, you notice something strange with your computer screen. The webpage that you’ve been staring at for the past hour begins to peel off the computer screen, flapping viciously like a piece of paper to a strong wind you cannot feel. As you try to press it down, it suddenly glues back onto the screen and stills. You are indoors, all windows are closed, and your roommate is looking at you strangely. At the moment, the nonexistent wind inside your room and the near escape of your homework problems seemed unquestionably real. This is an account from an individual who experienced psychosis, specifically during their experience with early psychosis.

Psychosis is defined as a condition where an individual experiences some degree of loss of contact with reality. Psychosis includes hallucinations and delusions. Hallucinations are characterized by false perceptions of reality often engaging the five senses. Those who experience hallucinations may see, hear, touch, smell, or taste things that are not actually present in reality– with visual and auditory hallucinations being the most common kinds of hallucinations. The experience described with the homework and wind is an example of a visual hallucination. Delusions include false beliefs and perceptions of the world around the individual and do not specifically focus on the five senses. People who experience delusions may persistently hold beliefs despite possible evidence contradicting their beliefs. The most common kinds of delusions are persecutory delusions, in which case the individual may believe that others are “out to get them” despite any lack of evidence. This can take the form of an individual believing that they are being spied on, that they are being followed, that they have hidden cameras watching them, or that others are plotting against them to cause harm to the individual– some common examples. Oftentimes, having psychotic experiences– particularly recurring psychotic experiences– is considered a symptom of a psychiatric disorder, such as for psychotic disorders like schizophrenia or delusional disorder, or for a mood disorder such as bipolar disorder. Psychosis is not a diagnosis in itself. While about 3% of the population have or will experience some psychotic event at least once, this does not mean that they must have a psychiatric disorder. Psychotic episodes may also occur in individuals without such disorders, usually from extreme stress, sleep deprivation, drug use, or a genetic predisposition, among other risk factors.

Early or first-episode psychosis (FEP) is the period of time during which an individual experiences their first psychotic symptoms. FEP usually occurs in people in their late teens and mid-20s, although there is no age restriction of when it can onset. Some positive symptoms of FEP, or the more active changes in behavior or thoughts, include delusions, hallucinations, and vague or odd speech, among other symptoms. Some negative symptoms, or symptoms characterized by the absence or decrease in normal behaviors, include abnormal facial inexpression, apathy, or withdrawal from family and friends, among other possible symptoms. Since FEP only marks the beginning period of time in which the individual begins to experience psychosis, it is not sufficient to diagnose a disorder based on FEP symptoms. Schizophrenia, for example, requires at least six months of persistent psychotic symptoms in order to be diagnosed.

Previous studies have suggested neuroanatomical differences in those who experience certain symptoms of FEP and healthy individuals. Some individuals who experience FEP symptoms find themselves impaired in their daily functioning. Researchers in a 2020 study searched for neuroanatomical differences in patients with such symptoms and healthy individuals. They used the University of California, San Diego Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA) to measure the daily functional ability of its participants, with a lower score in the UPSA pointing to a lower functional capacity in potentially-common aspects of their lives, including skills in the finance, transportation, communications, household maintenance, communication, and planning.

The research study found some potential trends for neuroanatomical abnormalities in participants with FEP compared to healthy controls. Along with different studies of the past, they found thinner cortices, or the outer layer of the brain’s cerebrum consisting of gray matter and important to consciousness and memory, in the frontal regions of the brain including the superior frontal, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) middle frontal, and fusiform regions. The frontal region of the brain controls more sophisticated executive functions, such as voluntary movement and language expression. The decrease in cortices implies a decrease in the density and size of neurons.

The study also found that, compared to the healthy participants who served as the control group, those with FEP had a decreased fractional anisotropy (FA) in the area of the brain called the right and left inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF), which is a white-matter path that connects multiple regions of the brain. FA is a measurement method that determines any changes in white matter and connectivity within the brain. A decreased fractional anisotropy reflects decreased white matter density and thus less connectivity between different regions of the brain. The decreased FA in the bilateral ILF, then, refers to the decreased white matter intensity between the areas that the ILF connects: the occipital lobes, which process visual information, and the temporal lobes, which receive the processed visual information from the occipital lobes and give it meaning. The decreases of FA in the left ILF, as observed in FEP, have also been previously recorded in schizophrenia and correlate to the presence of visual hallucinations. The ILF also plays an essential role in social functioning such as accuracy in an individual’s ability to detect facial expressions and emotions. However, such observations are complex, according to the study, and may be sensitive to error. Overall, the study suggests that such neurological differences between participants with FEP and those without are worth noting, though more sensitive methods of measurement should be developed and used in future studies to ensure greater accuracy.

Another study published in 2009 also focused on the neurological differences, this time in the hippocampus region in individuals experiencing psychosis, individuals at risk for psychosis, and healthy individuals. The hippocampus is heavily involved with brain regions such as the frontal lobe, which has been observed to have been impacted in the case of psychotic symptoms and schizophrenia. Within the small sample size of this study, those with first-episode psychosis showed a 4.5% decrease in left hippocampal volume compared to healthy control participants.

Some studies also suggest differences in neuroanatomy even among FEP patients experiencing different symptoms. Persistent apathy is yet another possible symptom of FEP, and a 2015 study suggests that there may exist correlations in different brain structures in those who experience FEP with and without persistent apathy. This study reported that FEP patients with persistent apathy tended to have significantly reduced in their left orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and left anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) compared to FEP participants without persistent apathy and healthy control participants. The OFC and ACC are regions of the brain that have been studied to have a role in motivation, which is an important aspect of goal-directed behavior. Thus, a reduction in these areas could be correlated to the decrease of these behaviors, potentially leading to the experience of persistent apathy. Studies of first-episode psychosis suggest a wide range of personal experiences and potential neurobiological differences between each individual.

No matter their symptomatic or potential abnormalities in neurobiological makeup, first-episode psychosis remains a critical stage for treatment to maximize positive response to treatment and potential recovery. There are programs in place that specifically treat individuals experiencing first-episode psychosis. The UC San Diego first-episode psychosis CARE program offers specialized and personalized outpatient care for young individuals who experience early psychosis. The care they provide to individuals participating in the program may include individual talk therapy, medication, group therapy and peer support, and continued after-recovery support. UCSD’s CARE program not only treats adolescents and young adults presenting with early signs and symptoms of psychosis, but also strives to better understand “the risk factors for developing psychosis and… identify people early before the onset of psychosis so that we can prevent some of the devastating effects of a first psychotic episode,” according to Dr. Cadenhead, MD, who serves as the director of the UCSD CARE program.

Psychosis comes in many different forms and experiences; however, stigma is one universally shared experience among those with psychosis as well as those who experience all other mental illnesses. Those who present with psychosis are often chalked up as “crazy,” and “delusional” becomes an insult. Such prejudice often minimizes their experiences. The stigma and misinformation surrounding psychosis often discourage those who begin to and continue to experience it from seeking proper support. It remains imperative to understand the range of psychosis and to support those who experience it.

An Interview with Dr. Cadenhead, MD

Dr. Cadenhead (kcadenhead@health.ucsd.edu) is a UCSD professor of psychiatry and an attending physician at the UCSD Medical center. She also serves as the director of UCSD’s CARE program.

CARE program website: https://psychiatry.ucsd.edu/research/programs-centers/care/index.html

SQ: In your professional opinion, what distinguishes first-episode psychosis from psychotic disorders or mood disorders?

Cadenhead: First-episode psychosis is the first sign of symptoms of a psychotic disorder… it’s when there are early changes in your thoughts, your perceptions, or your behavior. It can be caused by a lot of different things. For example, some people can get psychotic if they take too many drugs or if they take a medication that might make them psychotic. But psychosis can also be caused by mental health disorders like schizophrenia, or sometimes people with mood disorders develop psychotic symptoms…you would have a first episode of psychosis before you have subsequent psychotic episodes, whether they’re caused by a mood problem or schizophrenia, for example.

SQ: Do you find that people who experience first-episode psychosis generally tend to experience certain common symptoms? For instance, are persecutory delusions or visual hallucinations usually the most commonly-experienced of the symptoms of delusions and hallucinations?

Cadenhead: …I don’t know that there’s any one symptom that’s more common than another, but some of the ones that we see early that are more predictive… are in the more persecutory or suspicious realm or thinking that they’re things happening that refer to them somehow, like they hear a song on the radio and think it’s put there just for them.

SQ: How might sleep deprivation affect an individual’s risk for psychosis?

Cadenhead: Sleep deprivation is a stressor in itself. [For] people who have psychotic symptoms, losing sleep could definitely contribute. Sleep deprivation is particularly important in people with bipolar disorder because losing sleep can help to bring on a manic episode that can also be associated with psychosis.

SQ: How might family history factor into an individual’s experience with psychosis? Do you find that people with family members who have a history of psychosis are more likely to also experience it? Is it mostly genetically predisposed?

Cadenhead: Yes… Psychotic illness runs in families. If you are an identical twin, your twin would have a 50% risk of also having a psychotic illness… There is a genetic component but it doesn’t explain the total risk. If a person who has psychosis has children, their children have a 10% risk. If both parents have psychosis, then their child has a 25% risk, whereas in the general population it’s about a 1% risk.

SQ: What is the ultimate goal of the first-episode psychosis program at UCSD?

Cadenhead: The goal is to first of all understand psychotic illness to a greater extent. One of the main things we’ve been looking at over the last 22 years has been… the risk factors for developing psychosis and [if we can] identify people early before the onset of psychosis so that we can prevent some of the devastating effects of a first psychotic episode. When psychosis hits young people, a lot of times when they’re around high school or college age… it’s a really crucial period for them developmentally… If [we] can prevent some of those things from happening in a person’s life, [we] could really improve it.

The other thing we do is we use a lot of biomarkers to try to understand psychosis and the early phases of psychosis. By understanding biomarkers better, we can help to predict illness… [and] also develop newer treatments or individualized treatments… like figure out what kind of psychosis they have early on so that [we] could target [their] treatments to that specific type of problem.

SQ: What words of advice might you have for people, especially young people such as students at UCSD, who might suspect that they experience first-episode psychosis or who might have been diagnosed with first-episode psychosis but are unsure of the next steps?

Cadenhead: UCSD… [has] some very good mental health services for students. There’s both the campus counseling, a college mental health through UCSD, and… the CARE program for early-psychosis signs and symptoms. At [CARE] program, we see a lot of young people who have had early signs of psychosis. Many of them continue to go to college… many of them have gone on to have a successful career, finish college, maybe even go to graduate school. [Experiencing psychosis] doesn’t mean that you can’t go on with your life and do what you want to do, but I think it’s really important to get care as early as possible… It’s always good to get checked out [and] help prevent something. You want to reduce your stress [and] get plenty of sleep, and see a professional who can tell [you] what’s going on.

SQ: What words of advice might you give to people whose loved ones are struggling with first-episode psychosis?

Cadenhead: I think that the support of friends and family is incredibly important to help advocate for that person and also realize that sometimes they may not be thinking clearly. Sometimes when people are developing psychotic symptoms, in the beginning they may have some insight that… [they’re] having weird experiences, but sometimes it gets to the point where they have no insight [and] don’t realize that people around them love them and are trying to help them… I think the family recognizes that sometimes when someone’s in that situation, you can’t talk them out of it or convince them that it’s not true, that in the moment that’s their reality [and] they think that’s really happening to them. The main thing is to be supportive of them [and] encourage them to get help for things that they are worried about… I also tell families that [they] need to advocate, like if they’re having some trouble getting help or [the family] doesn’t think [the patient] is getting the help they need, help to advocate and get them into help, because sometimes if you’re ill, it’s very hard to do it on your own.

SQ: What are some under-studied topics in first-episode psychosis do you believe needs more research? How might these studies impact the field of psychiatry and general understanding of first-episode psychosis?

Cadenhead: I think we still need to develop better treatments and better interventions. We do have some really great research going on at this time where we’re looking at multiple biomarkers. It may be that there are specific treatments that correspond with that particular biomarker… I think that we need to work on personalizing [treatment] as much as possible and getting people the help they need as soon as possible after the symptoms start.

Currently, the CARE program is conducting studies on biomarkers that compensates participants for. Those who experience first-episode psychosis and those who don’t have a history of mental health illness can participate in the study.

The program is running a study on family therapy and is providing family support and education to those who have these symptoms.

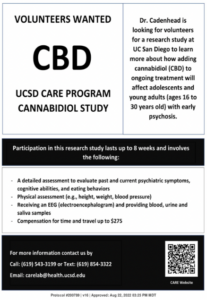

The program is also running a trial using cannabidiol (CBD) as a possible method to improve biomarkers of first-episode psychosis. Participants in the study are individuals who are at clinical high risk for psychosis or have experienced first-episode psychosis within the past two years.

The UCSD CARE program also currently runs a diet study researching how dietary intervention might improve psychological and physical health in individuals with recent experience with first-episode psychosis.

If you need clinical assessment or would like to be considered for research, please contact the CARE program (carelab@health.ucsd.edu) or Dr. Cadenhead (kcadenhead@health.ucsd.edu).

CARE studies: https://psychiatry.ucsd.edu/research/programs-centers/care/research-studies.html

Sources:

- https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/understanding-psychosis#:~:text=Psychosis%20may%20be%20a%20symptom,or%20any%20other%20mental%20disorder.

- https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/psychosis/overview/#:~:text=Psychosis%20is%20when%20people%20lose,not%20actually%20true%20(delusions)

- https://www.webmd.com/schizophrenia/guide/what-is-psychosis

- https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/guides-and-publications/first-episode-psychosis-guide-en.pdf

- https://www.healthline.com/health/psychosis

- https://www.dhs.pa.gov/Services/Mental-Health-In-PA/Pages/First-Episode-Psychosis.aspx

- https://www.hca.wa.gov/free-or-low-cost-health-care/i-need-behavioral-health-support/early-signs-psychosis#:~:text=The%20onset%20of%20first%20episode,psychosis%20to%20present%20in%20childhood.

- https://dictionary.apa.org/positive-symptom

- https://dictionary.apa.org/negative-symptom

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4568-schizophrenia

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33056996/

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/23073-cerebral-cortex#:~:text=Your%20cerebral%20cortex%20is%20the%20outer%20layer%20that%20lies%20on,fibers%20called%20the%20corpus%20callosum.

- https://www.health.qld.gov.au/abios/asp/bfrontal#:~:text=The%20frontal%20lobes%20are%20important,order%20to%20achieve%20a%20goal.

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19939408/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25818626/

- https://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/understanding-psychosis-and-finding-help-early/

- https://health.ucsd.edu/specialties/behavioral-mental-health/first-episode-psychosis/Pages/default.aspx#:~:text=With%20early%20intervention%20and%20treatment,Warning%20signs%20of%20psychosis