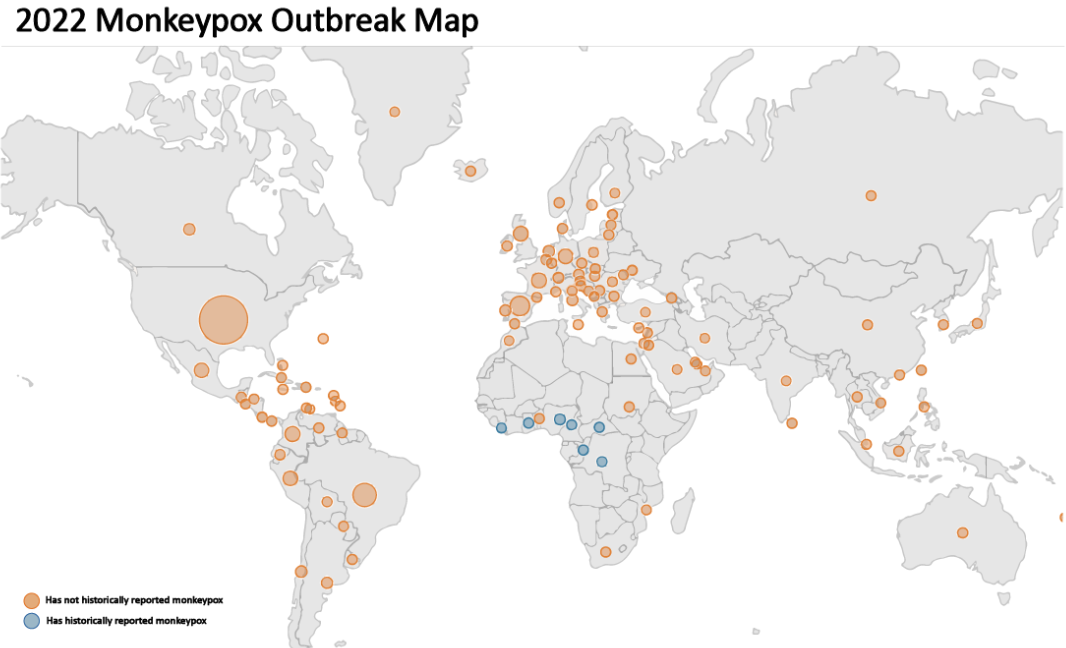

On July 23, 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced disappointing news regarding another Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) to nations across the globe—the monkeypox outbreak. Describing the sudden wave of cases as “atypical” the organization found a majority of the cases in Europe with fewer cases dispersed throughout other regions of the world. With approximately 49,900 cases globally (as of September 2022), the number of reported cases and their isolated locations currently suggest that the disease is an epidemic.

For most, this can and has induced a sense of fear. As a new academic year approaches on many college campuses, specialists are worried that although the current monkeypox populations remain isolated in certain areas, it will not take much time for the disease to expand as a social network is established between peers. This concern has already been voiced by UC Berkeley, which is preparing its campus for an “uptick of cases” due to an exponential growth of monkeypox outbreaks in the Bay Area. University Health Services spokesperson Tami Cate stated that the “campus has already treated a ‘few’ cases” and is beginning a vaccination program for its students. It is understandably exhausting for the world to consider enduring the effects of another wave of disease, especially since the current COVID-19 pandemic persists and communities seek to return to their normal. The real question is, will the monkeypox surge continue to keep us six feet apart, or is it a roadblock to bringing us six feet closer?

A good place to start answering questions would be to gain a better understanding of the virus itself and explore the differences between the monkeypox virus and SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

First reported in the 1970s, the human monkeypox virus was linked to an increasing amount of cases within Central and West Africa. However, despite its early origins, the true virulence of monkeypox is not yet known. This stems from the fact that the severity of the disease varies across regions. The severity of the disease corresponds to the case fatality ratio, the ratio of people who die from disease to all individuals diagnosed with the disease over a certain period of time. For example, in 1996 the Democratic Republic of the Congo faced a monkeypox surge with lower fatality ratios but higher transmission rates than usual. However, in 2017, the continuing outbreak in Nigeria led to a larger fatality ratio of approximately 3%. This variation in the severity of the disease has not been unseen by the world because similar case fatality ratios are represented in countries with SARS-CoV-2 today. The case fatality ratio of COVID-19 ranges from 0.1% to 5.3% in every country. These numbers may seem small to most, but they correspond to millions of people worldwide. It is not unreasonable to assume that monkeypox is and will increasingly become a matter of global public health importance.

Spreading into the world starting in 2003, monkeypox zoonosis (a disease that can be transmitted from animals to humans and vice versa), in the form of transmission from prairie dogs, first affected the United States. This outbreak preceded cases spreading to “Nigeria, to Israel in September 2018, to the United Kingdom in September 2018, December 2019, May 2021, and May 2022, to Singapore in May 2019, and to the United States of America in July and November 2021.” It has been known that monkeypox virus exists in non-endemic countries ever since 2017; doctors outside of African states have rarely been concerned about the transmissibility of the virus and the past waves of outbreaks have fizzled on their own. However, the recent spread of the disease appears exponential as communities return to social luxuries and increasing urbanization after a two-year hiatus. Due to the rarity of the outbreaks, much is still to be understood about the virus itself although other viruses of the same genus (ie. cowpox, smallpox, etc.) have been studied for decades. Studies are currently in progress to understand the transmission, epidemiology, and sources of infection.

However, here is what we do know about the virus from previous outbreaks.

Connected to the smallpox virus which was famously eradicated in 1980, monkeypox is a viral zoonosis belonging to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) virus, although much less clinically severe, resembles viral properties and symptoms seen in smallpox patients. The monkeypox virus has two predominant clades which are sourced from different waves of outbreaks throughout the years— the Central African clade and the West African clade. These clades are now termed Clade I and Clade II, respectively, as of 2022. Clade I is a harsher form of the virus, thought to be communicable, but all cases today have been confirmed to be of the milder Clade II by PCR testing. SARS-CoV-2 is a single-stranded RNA virus. Consequently, many variants of the virus exist as RNA viruses mutate to evolve in response to their geographic or physical environment. Mutations in viruses are not unheard of as all viruses mutate over time, but we do not expect to see as many mutations of the monkeypox virus. This is primarily supported by the fact that most DNA viruses have additional stability compared to RNA viruses that mutate faster, and single-stranded genomes tend to mutate faster than double-stranded genomes.

The monkeypox virus has two ways of transmission— zoonotically or human-human. The virus spreads by zoonosis from direct contact with the bodily fluids of infected animals. Humans can infect animals in their homes in the same manner; therefore, it is recommended that people avoid contact with their pets for 21 days after the most recent contact to avoid further spread of disease within the family. In humans, monkeypox spreads through close or intimate contact (often skin-to-skin contact) or direct contact with rashes, scabs, and bodily fluids of an individual infected with the monkeypox virus. Monkeypox can also be transmitted through contact with contaminated fabrics, objects, and surfaces. Since monkeypox requires prolonged, close contact, it is tougher for monkeypox to be transmitted compared to SARS-CoV-2, which could be transmitted within six feet of distance between individuals. The prolonged exposure required for transmission puts health workers, household members, and close friends at the greatest risk of contracting the illness. Unlike SARS-CoV-2, research reveals that monkeypox can spread to the fetuses of pregnant mothers through the placenta, and perhaps become a congenital issue for fetuses or lead to potential pregnancy complications that are yet to be discovered.

Like all viruses, the signs and symptoms of the monkeypox virus bear some similarities to SARS-CoV-2. These signs include fever, chills, exhaustion, muscle and body aches, headaches, and respiratory symptoms (sore throat, nasal congestion, cough, etc) that can be best described as flu-like. One specific feature that distinguishes monkeypox from SARS-CoV-2 is the formation of a rash that can be located near the genitals and spread near the hands, feet, mouth, chest and face. The rash initially forms small, inflamed blisters— quite similar to the commonly dreaded pimple— that may be painful or itchy. First, a few blisters appear, however, a multitude of satellite lesions or widespread bumps rapidly appear on the body within three weeks of exposure to the virus. After a few weeks, the scabs slowly crust over and fall off before healing. The virus can be spread from the onset of symptoms until the rash has completely healed and all scabs have fallen off to form a fresh layer of skin, so it is recommended for people to avoid contact with anyone who does have a rash and wear a mask for extra protection.

One clinical benefit of these lesions is that people are aware they are infected and are less likely to come into close contact with others after experiencing symptoms, potentially mitigating the transmission of the virus. The combination of COVID-19 and flu season led people astray regarding the true nature of their symptoms; moreover, people were unaware of how many people acquired COVID-19 as some individuals expressed signs of infection while others had no symptoms at all. In monkeypox, because the identifying symptoms are apparent, communities are recommended to avoid close contact with those who experience multiple rashes and wear a mask as additional protection beforehand to mitigate chances of transmission.

However, risks do remain for those who are immunocompromised, have multiple sexual partners, and healthcare or laboratory workers working with Orthopoxyviruses. Data suggest that the majority of cases involving monkeypox currently are associated with gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Healthcare officials strongly emphasize that anyone regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity can contract the virus from close and intimate contact. The current method of prevention for those who are at risk of contracting the virus the most is vaccination. Vaccination against the smallpox virus was demonstrated to be highly effective in preventing monkeypox and producing milder symptoms in patients. Currently, the most preferred vaccine to protect against monkeypox is JYNNEOS which is a two-dose vaccine. Another alternative is the ACAM2000 vaccine which is a single-dose vaccine that has more potential for adverse side effects, thereby reducing its potential for effectiveness for those who are immunocompromised. Currently, due to the panic-induced in health-conscious Americans, the demand for the vaccine exceeds the supply as the United States government scrambles to supply more vaccines for the public in their new initiatives.

So with all evidence combined, is monkeypox the new COVID-19? Will the world have another pandemic at its hands? With good hygiene, awareness of the disease, and low prolonged contact with those who have rashes, lesions, and illness, the spread of monkeypox can be avoided early. Additionally, we have good preventative measures to battle more severe illnesses such as vaccines, and COVID-19 social distancing procedures. However, although the disease signs are more obvious and allow effective time for people to isolate themselves from individuals with monkeypox, the rate of transmission is still effective enough for us to take necessary precautions for ourselves and others. There are still individuals who are immunocompromised with a great risk of acquiring more severe effects of the disease. Additionally, monkeypox may have unknown generational effects by transmissions to pregnant women. We must work together, yet again, to avoid more drastic effects in the future.

Sources:

- https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/23-07-2022-who-director-general-declares-the-ongoing-monkeypox-outbreak-a-public-health-event-of-international-concern

- https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/world-map.html

- https://www.dailycal.org/2022/08/03/campus-prepares-as-monkeypox-spreads-through-bay-area/

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox

- https://www.britannica.com/science/case-fatality-rate

- https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3048946/

- https://www.npr.org/2022/08/16/1117659506/monkeypox-variant-world-health-organization

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27392606/#:~:text=Rates%20of%20spontaneous%20mutation%20vary,correlate%20negatively%20with%20mutation%20rate.

- https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/prevention/pets-in-homes.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/pregnancy.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/symptoms/index.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/prevention/index.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/vaccines/index.html