By Meena Kian | Online Reporter | SQ Online (2019-2020)

As sentient beings, we have evolved to experience a vast and complex spectrum of emotions that serve important functions. Our emotions drive our adaptation to different circumstances, guide communication with others, and enable self-preservation through the avoidance of recurring sources of harm. Positive emotional experiences, such as feelings of gratitude in the presence of loved ones or excitement at the sights and scents of delicious foods, assure our bodies that we are safe and fulfilled. Similarly, negative emotions, such as grief following a great loss or fear in moments of danger, teach us to stay safe and prioritize meaningful relationships. For most of us, sentience in both its positive and negative forms helps us survive and thrive; for most of us, it is a sign of cognitive functioning and neurological health.

But what if our negative emotions failed to switch off? What if the grief following the loss of a loved one continued to shadow over us, making tasks as simple as getting out of bed or going to work feel intolerable? For those suffering from depression, the profound persistence of grief is insurmountable, and in severe forms, even debilitating.

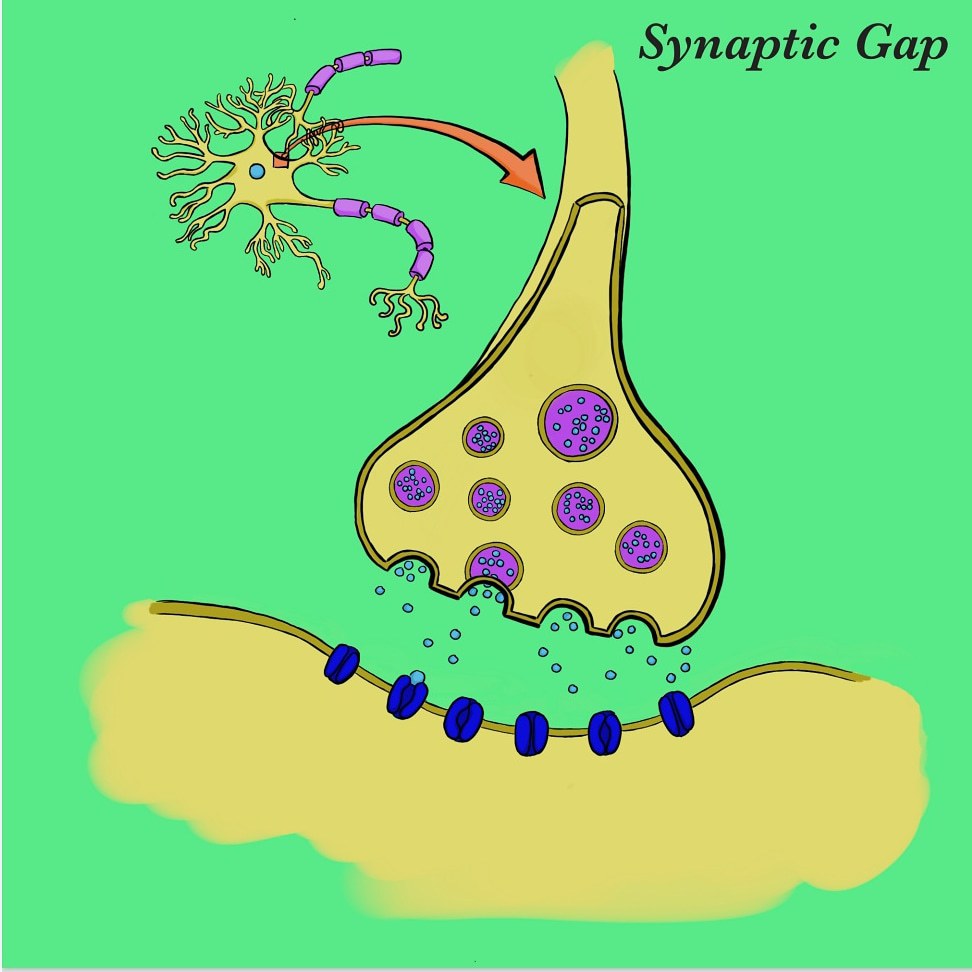

Like many other features, our feelings are primarily rooted in physiological mechanisms. Such mechanisms take the form of biochemical pathways in our brains and largely constitute the output and perception of all of our emotions. These networks involve a variety of chemical messengers, called neurotransmitters, eliciting diverse neural responses in regulatory processes. Cognitive disorders such as depression often relate to impairments in the serotonin pathway, resulting in prolonged periods of low mood, fatigue, and social withdrawal.

Serotonin is an important molecule that functions as both a hormone (a regulatory chemical substance which travels through fluid) and a neurotransmitter (a neuronal chemical messenger). As a hormone, serotonin participates in several processes of the body. For example, it elicits the expulsion of toxins during digestion, enables formation of blood clotting after injury and is vaguely linked to the onset of sleep cycles. As a neurotransmitter, serotonin plays an important role in mood regulation within the central nervous system.

The transmission of serotonin is initiated by the release of serotonin-containing vesicles at the axon terminal of a presynaptic neuron. The neurotransmitter then crosses the synaptic cleft before ultimately reaching metabotropic G protein-coupled receptors on a postsynaptic neuron, and induces a second-messenger cascade within that neuron. The binding of serotonin is moderated by a monoamine transport protein known as the serotonin transporter (SERT). SERT promotes the reuptake of serotonin from the synaptic cleft back into the presynaptic neuron, resulting in decreased synaptic transmission and therefore lower postsynaptic binding.

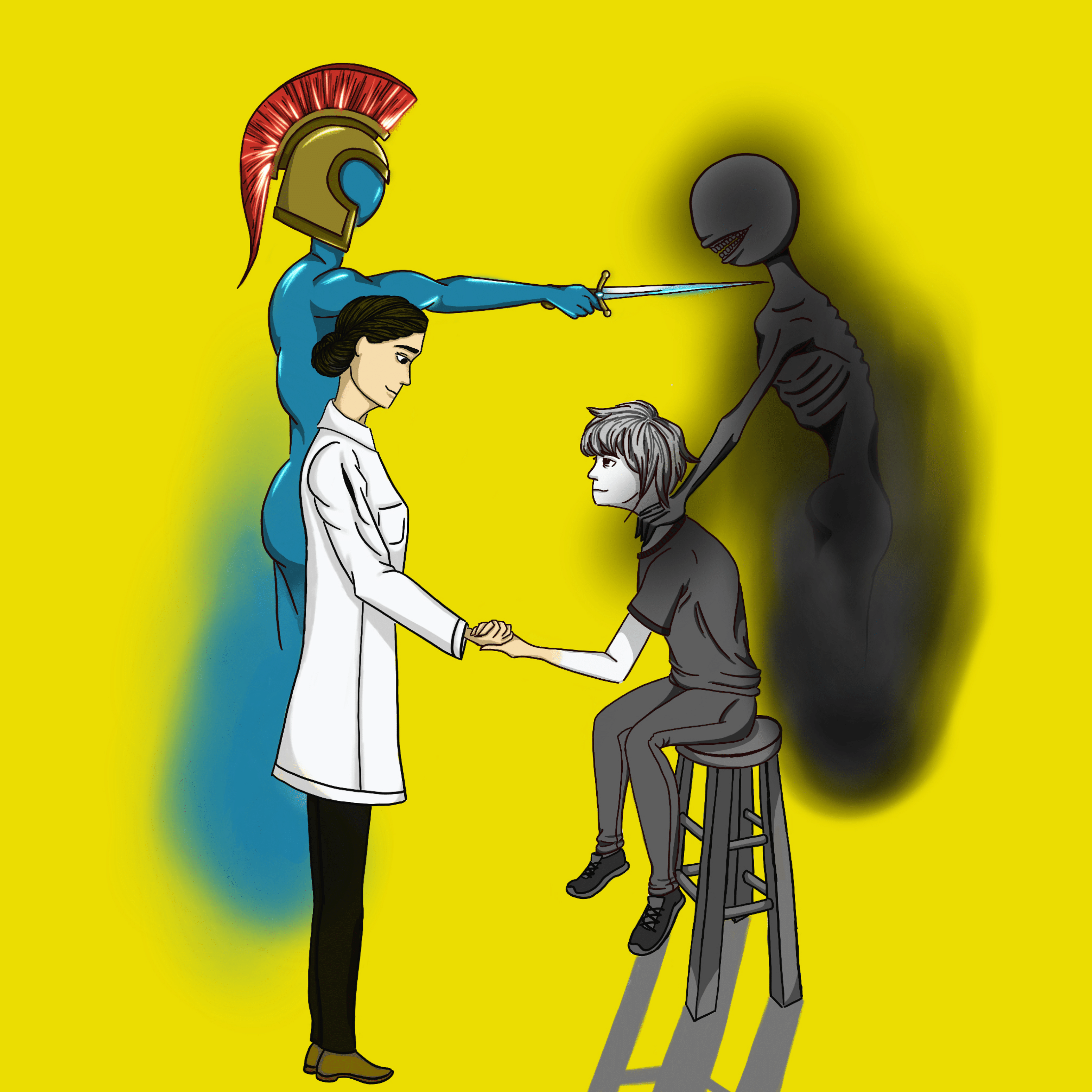

By pharmacologically amplifying a serotonin- induced response, mood can be elevated. More specifically, by inhibiting SERT and preventing serotonin reuptake, more serotonin remains in the synaptic cleft and activates a greater number of G protein-coupled receptors.

The leading theory on the biology of depression is explained by a lower number of serotonin receptors on postsynaptic cells, resulting in less signal transmission and expression. The inhibition of SERT, which compensates for the decreased binding affinity in patients with depression, is made possible by a class of antidepressants known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

The mechanism of SSRIs were first conceptually developed in the mid-20th century in response to scientific theories suggesting a link between decreased serotonin concentration and major depressive disorder (MDD). In 1975, such hypotheses physically materialized into the production of fluoxetine (better known by its market name Prozac), the first official SSRI in the United States. After gaining FDA approval in December 1987 and beginning distribution the following month, fluoxetine set the scene for a variety of future SSRIs. Prozac became the first of its kind to clinically alleviate depressive symptoms while avoiding hypertension (high blood pressure) and tachycardia (high resting heart rate), two major adverse effects associated with prior classes of antidepressants.

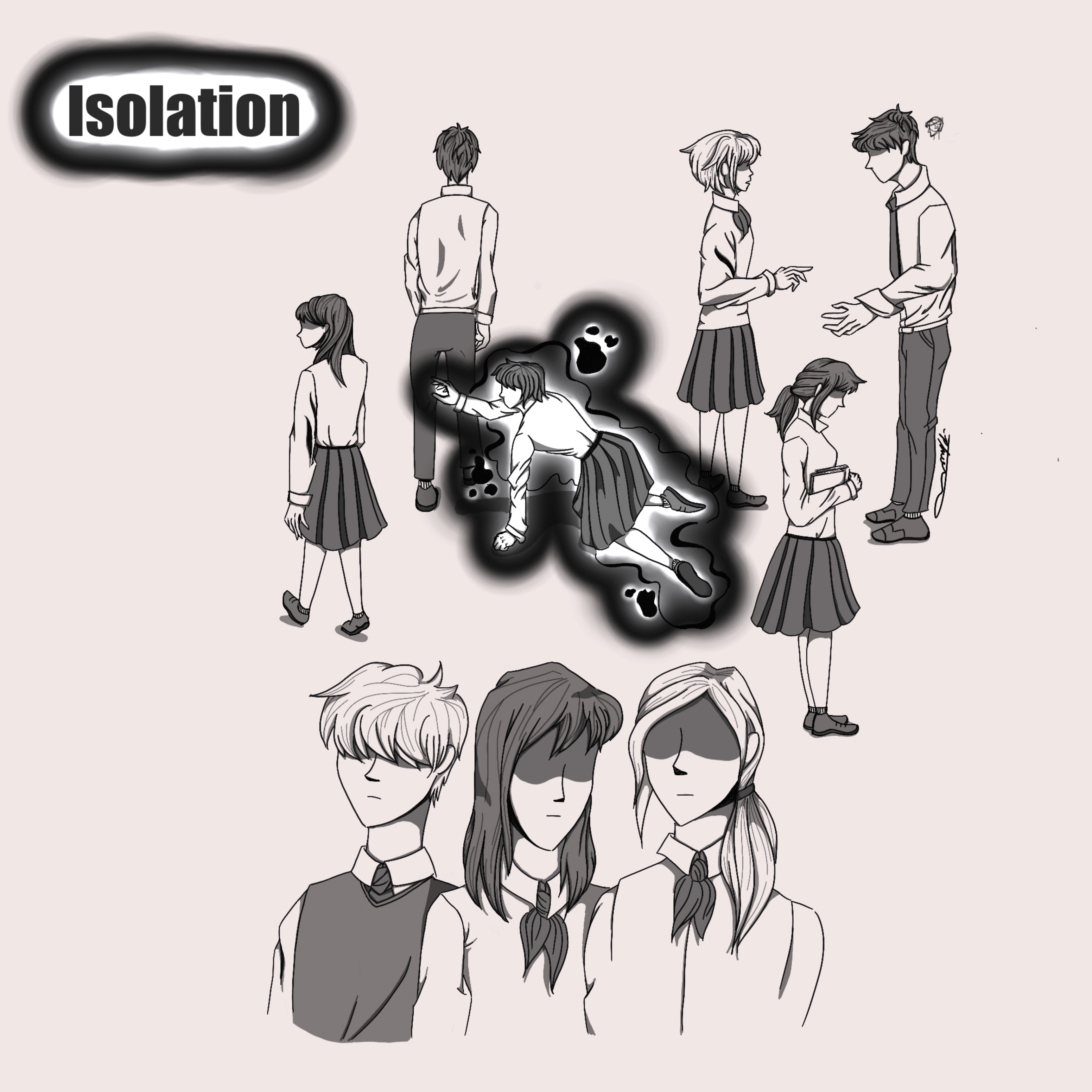

Despite SSRIs’ benefits in combating depression, they have been a subject of ongoing controversy in regards to both efficacy and a broader historical misperception of mental health. The ancient and persistent stigmatization of mental illness largely precedes the onset of the pharmaceutical industry. During the Middle Ages, for example, public perception of mental illness was shaped by the religious superstition that victims of mental illnesses were facing “punishment from God.” The ill were often persecuted and sentenced to death as a result of the substantial discrimination against them. During the Enlightenment era, social persecution of the mentally ill nearly ended, and institutions were established as a source for treatment and recovery. However, many negative connotations continued to surround and harm the mentally ill. A framing of psychiatric illnesses as crazy, religiously disillusioned, or even unsubstantiated coincides with systemic misregulation in a lack of funding for mental health research and resources.

In addition to societal barriers, the clinical efficacy of SSRIs has been arguably conditional. Since their emergence, alternative theories regarding the influence of other biochemical components, namely dopamine and norepinephrine, have continued to develop. Several randomization studies also present that patients with less severe depression (non-MDD) are likely to benefit simply from placebo pills in the absence of induced physiological modifications such as reuptake inhibition, indicating a comparable psychological benefit from the mere gesture of medicinal intervention. Such studies raise questions pertaining to the role of serotonin across various degrees of depression. Should non-MDD be treated medicinally? Is serotonin always responsible for symptoms of depression?

Unfortunately, the absence of a definite and uniform cause for depression across patients hinders precise intervention, as certain forms of the illness are caused by various biochemical and contextual variables that require detail-oriented diagnoses.

For instance, a concern in the medicinal treatment of depression is the intricacy of depression-mimicking symptoms. The prevalence of patient-reported symptoms coinciding with the psychiatric definition of depressive mood disorder yields a high false-positive diagnosis in many patients. Meanwhile, common medications, such as antihypertensive pills, antibiotics and antidiuretics share prolonged side effects of low mood, fatigue, or weight loss. Similarly, deficiencies in iron, Vitamin D, Vitamin B, and magnesium are often associated with malaise or irritability.

Additionally, a “one-size fits all” approach poses long-term repercussions for certain patients. Many patient-reported symptoms along the spectrum of depressive disorder are due to repressed trauma or unhealthy physical or social conditions present in their lives. Depending solely on medication to remedy symptoms can therefore neglect underlying causes of the illness, resulting in a bandaid effect that leaves patients with a lifelong dependency on antidepressants such as SSRIs.

Despite the complications of depression’s diagnosis and treatment, SSRIs are the most common and profitable antidepressants used today. Their efficacy, whether psychological or physiological, drives an exponential growth in antidepressant medications with the overall rate of antidepressant usage increasing 400% (between 2005 and 2008).

As the leading cause of disability, depressive mood disorder is a significant and ongoing global health problem. With SSRIs at the forefront of the modern pharmaceutical industry, it is important to analyze the context of their usage and consider both systemic and pharmaceutical modifications needed for higher treatment efficacy. While the diagnostic and treatment process should be personalized for each patient in consideration of their health history, the research supporting the efficacy of SSRIs particularly shows room for improvement. Furthermore, the social and systemic barriers to accessing psychiatric treatment suggest social space for reformation in the pursuit of sustainable health outcomes.

Sources:

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2267800/

- https://www.hormone.org/your-health-and-hormones/glands-and-hormones-a-to-z/hormones/serotonin

- https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/5270/the-molecular-mechanism-behind-synaptic-transmission

- https://web.williams.edu/imput/IVB3.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4428540/

- https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/psychopharmacology/short-history-ssri

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolutionary-psychiatry/201106/the-evolution-psychiatry

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5007563/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2412901/

- https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/64736/schizophrenia-other-psychotic-disorders/recognizing-mimics-depression-8-ds

- https://www.aarp.org/health/drugs-supplements/info-06-2012/medications-that-cause-chronic-fatigue.html

- https://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/06/college-students

- http://www.whp-apsf.ca/pdf/SSRIs.pdf

Image Credits:

- Cover photo by Mark Jacob and Jason Dagoon

- Illustration 1 by Phoebe Ahn

- Illustration 2 by Phoebe Ahn

- Illustration 3 by Phoebe Ahn