By Briana Kusuma | UTS Staff Writer | SQ Online (2014-15)

Almost everyone has had spicy food in their lives, especially college students; just think of all of those bottles of sriracha you’ve used or bags of hot cheetos you’ve eaten. To those who already like the kick that spicy food gives them, there may actually be even more countless benefits to this diet than they realize–more specifically, when spicy peppers (such as jalapenos) are added to your dishes.

Under the direction of Eyal Raz, MD, a team of scientists at the UC San Diego School of Medicine has found that capsaicin, the molecule responsible for the “burn” from eating spicy food, can reduce the development of intestinal tumors in mice by constantly activating a receptor called TRPV1.

TRPV1 is normally found in neurons, where it senses harmful changes in the cell’s environment. However, it can also be found in intestinal cells. In the gut, TRPV1 is activated by the epidermal growth factor receptor, also known as EGFR. EGFR helps the intestinal lining grow new cells to replace old ones that have died, a process that repeats every four to six days; if left unrestrained, there may be an overgrowth of cells that eventually form tumors and lead to colon cancer in the large intestine. Once activated, TRPV1 prevents this by reducing the amount of EGFR in the intestine.

The mice who lacked normal levels of TRPV1 developed more intestinal tumors than those who had normal levels of the receptor. However, when Raz’s team began feeding these TRPV1-deficient mice with diets high in capsaicin, they found that the rate of intestinal tumor formation dropped–and even expanded the lifespans of the mice by more than thirty percent.

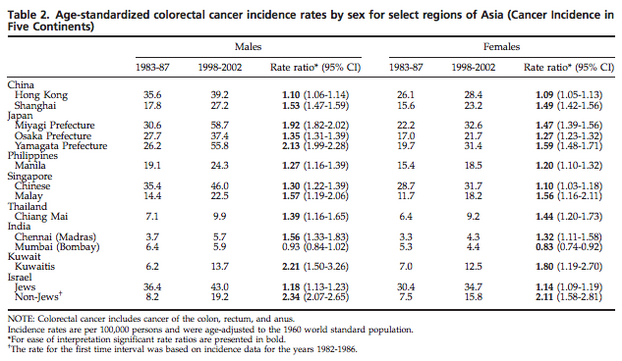

There are also studies, such as the one in 2009 about international colon cancer incidence, showing that countries, such as Thailand and India, whose foods often utilize spicy peppers tend to have lower rates of colon cancer than countries that do not use spicy peppers as much, such as China and Japan. Despite this link, one needs to consider that this study does not take into account the many differences in cultures and cuisines between these nations.

It is important to note that there is currently no established link between TRPV1-deficiency and colon cancer in humans, though there are clinical implications for a possible therapy involving capsaicin if future studies show the two events correlate.

Additionally, there has been proof that consuming capsaicin also aids in weight loss by increasing metabolism. Older research done by Dr. Mayumi Yoshioka’s lab added capsaicin to the breakfasts of thirteen Japanese women. All of the subjects were told to eat as they usually did and refrain from exercising before eating the experimental meals; they were then given surveys to indicate how full or hungry they were.

It was found that adding capsaicin to the meals made the women less inclined to eat later, and decreased the amount of protein and fat that their bodies absorbed. Capsaicin also increased the activity of the sympathetic nervous system, which in-turn increased fat oxidation (commonly known as “burning fat,” where your body uses fat reserves as an energy source by breaking the large fat, or lipid, molecules into smaller ones). Both effects paved way to moderate weight loss.

Based on these studies, it may not hurt for people to continue eating spicy foods–so next time you find yourself wondering whether to add sriracha to your noodles or jalapenos to your nachos, go ahead and add a dash; it might be beneficial for your health.

[hr gap=”0″]

Sources:

- Center, Melissa M., Ahmedin Jemal, and Elizabeth Ward. “International Trends in Colorectal Cancer Incidence Rates.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, & Prevention 18 (2009): 1688-1694. Web. 23 Sep. 2014.

- de Jong, Petrus R., et al. “Ion channel TRPV1-dependent activation of PTB1B suppresses EGFR-associated intestinal tumorigenesis.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation 124 (2014): 3793-3806. Web. 23 Sep. 2014.

- Ludy, Mary-Jon, George E. Moore, and Richard D. Mattes. “The Effects of Capsaicin and Capsiate on Energy Balance: Critical Review and Meta-analyses of Studies in Humans.” Chemical Senses 37 (2012): 103-121. Web. 7 Jan. 2015.

- Yoshioka, Mayumi, et al. “Effects of red pepper on appetite and energy intake.” British Journal of Nutrition 82 (1999): 115-123. Web. 7. Jan. 2015.

Image Sources:

- https://www.google.com/url?q=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.flickr.com%2Fphotos%2Fchubbybat%2F1250020095%2F&sa=D&sntz=1&usg=AFQjCNEt9cykQPLZ4YJVoZXohNVCoAfYJg

- http://www.lipidmaps.org/update/2010/100701/full/lipidmaps.2010.20.html

- http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/18/6/1688.abstract

- http://www.top10thailand.in.th/10%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%B1%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%94%E0%B8%B1%E0%B8%9A%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%AB%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%A3%E0%B9%84%E0%B8%97%E0%B8%A2/%E0%B8%95%E0%B9%89%E0%B8%A1%E0%B8%A2%E0%B8%B3%E0%B8%81%E0%B8%B8%E0%B9%89%E0%B8%87/